|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Jayant Kumar Ghosh, Sundeep Kumar Goyal, Sangey Chopel Lamtha, Pankaj Kaushik, Manas Kumar Behera, Abhilash VB, Vinod Kumar Dixit, AK Jain

Department of Gastroenterology, Institute of Medical Sciences,

Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP- 221005, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Jayant Kumar Ghosh

Email: drjayantkg@yahoo.co.uk

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.232

48uep6bbphidvals|690 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext This is the first case report of colonic spirochetosis from a tropical country like India. Clinicians should consider rare diagnosis like colonic spirochetosis if chronic dysentery is not responding to common medical treatment. Colonoscopy with multiple biopsies and a good histopathologic examination by an experienced pathologist should be done. Prognosis is favorable with medication. The clinical significance of intestinal spirochetes in humans remains highly debated. It remains unclear whether the presence of microorganisms coating the intestinal mucosa signifies mere colonization or disease.

Case report

A 10-year-old boy presented to our Gastroenterology outpatient department with the complaints of blood-mixed loose stools since last three months. He reported up to 10 bowel movements per day associated with lower abdominal pain and cramping that was relieved by defecation. He had lost 5 kg weight over last three months. He was treated at another hospital with various combinations of antibiotics, probiotics and anti-diarrheal drugs without any improvement in symptoms. On physical examination, the patient was in no acute distress. He was afebrile with a pulse rate of 68 per minute and respiratory rate of 17 per minute. Cardiac, abdominal, respiratory and nervous systems were unremarkable. An initial laboratory workup included complete blood count, stool for routine-microscopic examination and stool culture. His hemoglobin was 9 g/dl and his stool was positive for occult blood. However, no ova, cyst or parasite was detected in the stool. Stool culture was negative. Colonoscopy was done which revealed three erythematous, edematous, elevated lesions with small superficial ulcers (2 to 3 mm) and normal intervening mucosa in the hepatic flexure and ascending colon (Figure 1).

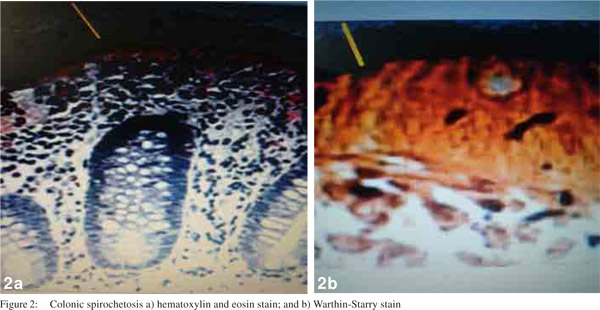

Histopathology by hematoxylin and eosin stain of the colonic biopsy revealed a fuzzy band on the surface of the enterocytes. This finding was highly suggestive of intestinal spirochetosis. These findings were further confirmed by Warthin-Starry staining, which revealed a moderate number of spirochetes in the colonic biopsies (Figure 2). Biopsies from esophagus, stomach and duodenum showed no pathology. Diagnosis of intestinal spirochetosis was made and the patient was put on oral metronidazole initially for 14 days. However, mild symptoms persisted even after 14 days and a repeat course of metronidazole was given for another 14 days. By the end of second course the patient improved clinically. Repeat colonoscopy after completion of therapy showed complete resolution of colonic ulcers. The patient was doing well till 12 weeks post-treatment follow-up.

Discussion

Adhesion of spirochetes to the mucosal brush border, resulting in its thickening as seen on light microscopy has been reported worldwide in both children and adults.[1] Brachyspira aalborgi and Brachyspira pilosicoli are members of Brachyspiraceae family. Both have been described in humans and are considered as cause of human intestinal spirochetosis.[2] Since 1997, Brachyspira spp. has been included in the list of human enteropathogenic bacteria.[3] Both these spirochetes are slow growing fastidious anaerobes and require specific media, with estimated growth times of 6 days for B. pilosicoli and up to 2 weeks for B. aalborgi. Morphologically, they are coiled Gramnegative bacilli and are motile in liquid environment due to presence of flagellae. Generally they are considered noninvasive but systemic spread of B. pilosicoli has been documented in critically ill patients.[4]

These spirochetes are susceptible to several antibiotics, such as metronidazole, meropenem, chloramphenicol, ceftriaxone and tetracycline, but 60% isolates are resistant to ciprofloxacin.[5] Mode of transmission is unclear, but is likely to occur by feco-oral route (contaminated water, colonized/ infected feces). Due to higher prevalence in homosexual men, sexual transmission has also been suggested.[6] Prevalence varies considerably across different geographic and immune conditions. In developed countries it ranges between 1.1-5.0%, with higher prevalence in homosexual men and HIV positive patients.[1] In most cases, intestinal spirochetosis is asymptomatic and presents incidentally during a screening colonoscopy for other reasons. However, infected children usually complain of persistent diarrhea, rectal bleeding, constipation, abdominal pain, weight loss, failure to thrive, nausea and lack of appetite.[5] The severity of disease can vary from asymptomatic colonization to invasive and rapidly fatal progression, but there appears to be no correlation between degree of immunodeficiency in HIV positive patients and the extent of disease.[1] Colonic involvement is documented from distal to proximal, including rectum and appendix.[6]

Discussion

Adhesion of spirochetes to the mucosal brush border, resulting in its thickening as seen on light microscopy has been reported worldwide in both children and adults.[1] Brachyspira aalborgi and Brachyspira pilosicoli are members of Brachyspiraceae family. Both have been described in humans and are considered as cause of human intestinal spirochetosis.[2] Since 1997, Brachyspira spp. has been included in the list of human enteropathogenic bacteria.[3] Both these spirochetes are slow growing fastidious anaerobes and require specific media, with estimated growth times of 6 days for B. pilosicoli and up to 2 weeks for B. aalborgi. Morphologically, they are coiled Gramnegative bacilli and are motile in liquid environment due to presence of flagellae. Generally they are considered noninvasive but systemic spread of B. pilosicoli has been documented in critically ill patients.[4]

These spirochetes are susceptible to several antibiotics, such as metronidazole, meropenem, chloramphenicol, ceftriaxone and tetracycline, but 60% isolates are resistant to ciprofloxacin.[5] Mode of transmission is unclear, but is likely to occur by feco-oral route (contaminated water, colonized/ infected feces). Due to higher prevalence in homosexual men, sexual transmission has also been suggested.[6] Prevalence varies considerably across different geographic and immune conditions. In developed countries it ranges between 1.1-5.0%, with higher prevalence in homosexual men and HIV positive patients.[1] In most cases, intestinal spirochetosis is asymptomatic and presents incidentally during a screening colonoscopy for other reasons. However, infected children usually complain of persistent diarrhea, rectal bleeding, constipation, abdominal pain, weight loss, failure to thrive, nausea and lack of appetite.[5] The severity of disease can vary from asymptomatic colonization to invasive and rapidly fatal progression, but there appears to be no correlation between degree of immunodeficiency in HIV positive patients and the extent of disease.[1] Colonic involvement is documented from distal to proximal, including rectum and appendix.[6]

Mucosal appearance on endoscopy is insufficient for diagnosing infection, since it can present as normal, polypoid, and/or erythematous mucosa, or merely as non-specific lesions.[7] The histologic appearance of spirochetes mimics a ‘false brush border’ formed by a layer of spirochetes.The surrounding cytostructure may show inflammation with slight oedema, infiltrate of monocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils in the lamina propria, as well as elongated and hyperplastic crypts. On electron microscopy, spirochetes are attached perpendicularly to the epithelial membrane of the enterocytes and the microvilli appear shortened or depleted. Histologically it is not possible to distinguish B. pilosicoli from B. aalborgi. Genetic methods have been developed to identify Brachyspira species from stool and tissue samples. Treatment strategies have been proposed for eradicating intestinal spirochetosis, including macrolides and clindamycin. But metronidazole seems to be the drug of choice, with a regimen of 500 mg 3 times a day for 10 days in adults and 15 mg per kg bodyweight 3 times per day for 5 days in children.[5] However, longer therapy may be required sometimes as in the present case where it took 28 days for complete recovery. Currently, there is little evidence for the most effective antibiotic agent as treatment response is variable and sometimes ineffective, supporting the hypothesis that these microorganisms are harmless commensals.[1] Spontaneous recovery has been described after a prolonged period for up to 8 months.[8]

References

- Tsinganou E, Gebbers JO. Human intestinal spirochetosis—a review. Ger Med Sci. 2010;8:Doc01.

- Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE. Phylogenetic foundation of spirochetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2:341–4.

- Bruckner DA, Colonna P. Nomenclature for aerobic and facultative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1–10.

- Bait-Merabet L, Thille A, Legrand P, Brun-Buisson C, Cattoir V. Brachyspira pilosicoli bloodstream infections: case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2008;7:19.

- Brooke CJ, Hampson DJ, Riley TV. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Brachyspira pilosicoli isolates from humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2354–7.

- Helbling R, Osterheld MC, Vaudaux B, Jaton K, Nydegger A. Intestinal spirochetosis mimicking inflammatory bowel disease in children. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:163.

- Alsaigh N, Fogt F. Intestinal spirochetosis: clinicopathological features with review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:97–100.

- Marthinsen L, Willen R, Carlen B, Lindberg E, Varendh G. Intestinal spirochetosis in eight pediatric patients from Southern Sweden. APMIS. 2002;110:571–9.

|

|

|

|

|

|