|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

|

Piyush Kumar Sharma,1 Tejas Menon Suri,1 Pratap Mouli Venigalla,1 Sushil Kumar Garg,1 Ghulam Mohammad,2 Prasenjit Das,3 Seema Sood,4 Anoop Saraya,1 Vineet Ahuja1

Departments of Gastroenterology

and Human Nutrition,1

Pathology,3 and Microbiology,4

All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, New Delhi.

Department of Medicine,2

Sonam Norboo Memorial

Government Hospital,

Leh, Ladakh,

Jammu and Kashmir, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Vineet Ahuja

Email: vins_ahuja@hotmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.224

Abstract

Background: Dyspepsia is a common symptom in residents of Leh, a high-altitude region in Ladakh, India. Helicobacter pylori related gastritis is a common cause of such symptoms. However data regarding this association at high altitudes is sparse.

Aim: To investigate the demographic, endoscopic and histopathology findings in patients presenting with dyspeptic symptoms in the high-altitude region of Leh. Methods: A crosssectional study was done in 84 patients with dyspeptic symptoms, attending the outpatient department of local government hospital in Leh. Demographic details, endoscopy, histopathology of upper gastrointestinal biopsies and microbiology culture of gastric/duodenal aspirates were studied.

Results: The mean age was 38.4 years with 42% being males. Indigenous foods with high-salt content were consumed by 75% of patients. Epigastric pain was the most frequent symptom (in 96%) and pain radiating to the back was another peculiar symptom seen in 49% of patients. The predominant finding on endoscopy was antral gastritis in 71% of patients. Nodular gastritis was seen in 18% of patients. H. pylori was documented in 93% and histopathology revealed mild-to-moderate inflammation in 93% and mild-to-moderate atrophy in 90% of patients. Colonization with Gram-negative bacilli was observed in gastric/duodenal aspirate cultures.

Conclusion: Dyspepsia at high-altitude commonly presents as pain radiating to the back with a very high (90%) prevalence of H. pylori, endoscopic findings of antral gastritis and nodular gastritis, and atrophic gastritis in biopsies. Further investigations are needed to determine whether these observations are related to the high-altitude or the high-salt content in their diet and also whether these further translate to carcinogenesis.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|682 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext The clinical expression of gastric inflammation is determined by the underlying etiology, host response, genetic susceptibility and environmental factors. Dyspepsia is the chief clinical manifestation of gastritis and its incidence has been reported to be 15.3 per 1000 person-years.[1] It is one the most common upper GI symptoms and hence isn’t specific for gastritis. 80% of all gastroscopies are performed for the investigation of dyspepsia, and an endoscopic diagnosis of gastritis is made in 59% of these although in only 3% are the changes severe.[2] There is no exact correlation between the endoscopy and histology findings, as well as their severity. In the northern part of India, Helicobacter pylori infection is seen in 56.7% asymptomatic individuals and in 61.3% with one or more symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia.[3] This discordance between the clinical and investigation findings often poses a great diagnostic dilemma in patients presenting with dyspepsia as their chief complaint.

Gastric pathology in patients residing at higher altitudes appears to be different from that in patients at sea level. A higher prevalence of H. pylori infection has been reported at high altitudes.[4] The severity of H. pylori associated pathology in the gastric mucosa of the antrum, body and to a lesser extent the cardia, also appears to be greater in patients living at higher altitudes. In addition, advanced gastric alterations, such as chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, are also more prevalent in these patients.[5]

Very few studies have examined the histopathology and clinical characteristics of gastritis in high altitude populations. The present study aimed to explore the histopathology and endoscopy findings in patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal symptoms in a high altitude region of India. We further wanted to determine if there is any relation between high altitude lifestyle or dietary factors and the severity of H. pylori associated pathology.

Methods

The Leh district is a part of the Ladakh region of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. It lies at an altitude of 3524 meters (11,562 ft) above sea level, and is bound by the Kunlun mountain range in the north and the Great Himalayas in the south. It is located between 32° and 36° latitudes north and 75° to 80° longitudes east. The current study is an audit of the data collected from two health camps conducted in Leh during the years 2006 and 2007. This included 84 patients presenting to the outpatient department of the local government hospital at Leh, with upper gastrointestinal complaints of dyspepsia.

A detailed clinical history was obtained regarding demographic and lifestyle factors including dietary habits and dressing pattern, symptom profile, previous H. pylori eradication treatment and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) intake.

The frequency and severity of symptom of epigastric pain was recorded. Severity was graded as mild, moderate and severe according to a visual analogue scale. Patients consuming meat less than once a month were labelled as vegetarians and only people who were currently smoking or taking alcohol regularly at the time of presentation were considered as smokers or alcohol-users. Salt tea (gur-gur tea) which is a very popular local drink is made of yak butter added to boiling water mixed with salt, soda, milk and an infusion of tea-leaves, called zarcha. Butter is considered by the locals as essential to keep the body warm in the cold climate. The Ladakhi dress is goncha, a voluminous robe of thick woolen cloth with a cummerbund tied at the waist worn with loose pyjamas, a top hat and long felt boots completing the ensemble. The patients were included in the study if transabdominal ultrasonography was normal with a normal gallbladder and pancreas.

All the patients were subjected to fiberoptic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (Olympus GIF, XQ20) and a careful assessment of the mucosal changes was done by an experienced endoscopist. The presence or absence of inflammatory changes was recorded in the esophagus, fundus, corpus, antrum and duodenum. The diagnosis of nodular gastritis was made when the mucosa had an irregular cobblestone pavement pattern with characteristic micronodules that measured 1–4 mm in diameter, with a smooth surface and was of the same color as the surrounding mucosa.

Biopsies were obtained from four sites: esophagus, corpus, antrum and duodenum and were sent for histopathology by a specialist pathologist for gastrointestinal diseases; who was blinded for any clinical or endoscopy information. The antrum and corpus specimens were examined for the presence and grade of mononuclear cell infiltrate (chronic inflammation), neutrophilic infiltrates (inflammatory activity), glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and H. pylori infection and scoring was done according to the updated Sydney System.[6]

The esophageal specimens were examined for inflammation, metaplasia, blood lakes and hyperplasia. The duodenal specimens were examined for inflammation, crypt-villous ratio, presence of any parasites and metaplasia. Pan-inflammation was said to be present when there were simultaneous findings of esophageal, antral, fundal and duodenal inflammation. The biopsies were transported within 72 hours in 10% formalin solution, to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi for further processing and examination. For a representative number of patients, gastric/duodenal aspirates were obtained and inoculated in liquid culture bottles and transported within 72 hours to AIIMS.

Informed consent was taken from each patient. The study was done in accordance with principles laid down in the Helsinki Declaration. Statistical analysis was done using Stata statistical software version 11 (StataCorp LP, Texas USA).

Results

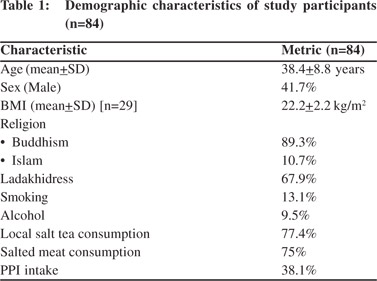

The demographic details of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the study population was 38.4 years and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.2 kg/m2. Of all the patients, 42% were men and almost 90% were Buddhists. All of them resided at an altitude of 3500 m above sea level or higher. 68% of the people reported that they wore the traditional Ladakhi dress as their primary garment whereas 77% regularly consumed the local salt tea, the average consumption being 5 cups a day. Nearly 10% were self-reported frequent alcohol users while 13% admitted to smoking regularly. Being situated at a high altitude, the Leh and Ladakh region does not have a regular or sufficient supply of fresh fruits and vegetables. The weekly intake of fresh fruits and vegetables in the study population during summers was 6 servings per week on an average. It was reduced to 2 servings per week during winters due to poor supply, inclement weather and lack of transportation. Understandably most of the inhabitants follow a non-vegetarian diet especially salted meat. Just under 2% of the patients had had a previous H. pylori eradication regimen and 38% had received PPIs for the treatment of their symptoms in the past.

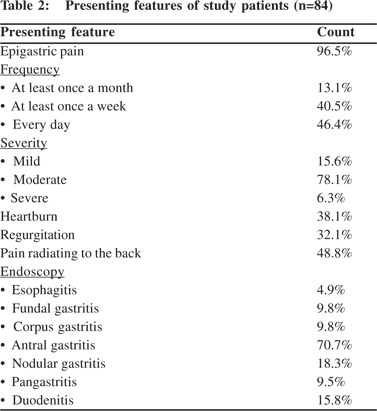

The modes of clinical presentation of the patients are given in Table 2. Majority (96%) of the patients had frank epigastric pain as their chief complaint and 46% of them experienced it every day. The pain was moderate in majority (78%). 49% patients also experienced pain radiating to the back. 38% had heartburn and 32% experienced regurgitation. Serum amylase was normal in all patients presenting with abdominal pain radiating to the back. In five patients who subsequently came to AIIMS for follow-up, endoscopic ultrasound for chronic pancreatitis revealed their pancreas to be normal. The findings of upper GI endoscopy are tabulated in Table 2. Endoscopy revealed antral gastritis in 71% patients, with signs of duodenal inflammation ranging from mild mucosal erythema to frank ulcerations and structural deformities in 16%. Similar changes were also observed in the corpus and/or fundus in nearly 10% of the patients. In 18% of the cases the endoscopic appearance of the mucosa was consistent with the diagnosis of nodular gastritis.

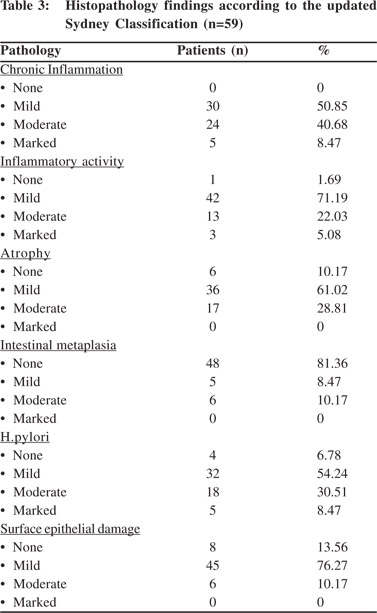

Of the 84 histopathology specimens only 59 were deemed adequate for an accurate classification and description of etiology, morphology and severity of gastritis according to the updated Sydney Classification System.[6] Histopathology results are summarized in Table 3. Histopathology revealed mild-to-moderate inflammatory changes in more than 90% of patients. Surface epithelial damage was found in 86% of patients. Mild-to-moderate atrophy was present in about 90% of patients. There was no intestinal metaplasia in 81% of patients. H. pylori was positive in 93% of patients, with a mildto- moderate infection density in majority. Gastric/duodenal aspirate cultures obtained from 15 patients revealed colonization with Escherichia coli in 4 patients, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 4, Enterobacter spp. in 2 and multiple organisms in 5. All of these organisms showed complete sensitivity to imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, netilimicin, piperacillin, cefoperazone/sulbactam and ticarcillin/clavulanate but resistance to cephalosporins, ciprofloxacin and piperacillin was observed in one of the P. aeruginosa isolates, and resistance to ciprofloxacin was observed in two other P. aeruginosa and E. coli isolates.

Of the 84 histopathology specimens only 59 were deemed adequate for an accurate classification and description of etiology, morphology and severity of gastritis according to the updated Sydney Classification System.[6] Histopathology results are summarized in Table 3. Histopathology revealed mild-to-moderate inflammatory changes in more than 90% of patients. Surface epithelial damage was found in 86% of patients. Mild-to-moderate atrophy was present in about 90% of patients. There was no intestinal metaplasia in 81% of patients. H. pylori was positive in 93% of patients, with a mildto- moderate infection density in majority. Gastric/duodenal aspirate cultures obtained from 15 patients revealed colonization with Escherichia coli in 4 patients, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 4, Enterobacter spp. in 2 and multiple organisms in 5. All of these organisms showed complete sensitivity to imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, netilimicin, piperacillin, cefoperazone/sulbactam and ticarcillin/clavulanate but resistance to cephalosporins, ciprofloxacin and piperacillin was observed in one of the P. aeruginosa isolates, and resistance to ciprofloxacin was observed in two other P. aeruginosa and E. coli isolates.

Discussion

Given the lack of correlation between clinical, endoscopic and histopathology findings in dyspeptic patients, gastritis poses a great diagnostic dilemma for gastroenterologists. Often these patients get clubbed with patients having markedly different presentations and investigation findings. With the discovery of H. pylori in 1982, chronic gastritis was proposed to be caused by repeated inflammatory insults to the gastric mucosa and subsequent atrophy because of incited by the infection. The updated Sydney System helps in making a more objective assessment of this condition.[6]

Epigastric pain, heartburn, regurgitation, bloating, nocturnal pain, belching, discomfort after meals, early satiety, nausea, postprandial fullness are usual presentations in dyspeptic patients with epigastric pain being the most common.[7] Pain radiating to the back is not a symptom usually reported in these patients. Such symptoms are characteristic of pancreatitis or penetrating peptic ulcer disease. However in the Ladakhi gastritis patients we examined besides epigastric pain, heartburn and regurgitation, pain radiating to the back was a unique presentation noted in nearly half of the subjects. Clinically significant endoscopy findings have been previously noted in 58% of 1040 patients presenting with dyspeptic symptoms to a primary care establishment in Canada.[8] An endoscopy finding of just gastritis was not considered as sufficient evidence in this study and only erosions, ulcers, Barrett’s esophagus, reflux esophagitis were considered clinically significant. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was 30%. In a study of 197 Tibetan patients with dyspeptic symptoms from South India, endoscopic evidence of ulcers, present or previous, was found in 18% of the patients; evidence of gastritis or duodenitis was found in 30% and H. pylori was positive in 77%.[9] In a community based study from Italy involving 1033 patients with or without dyspeptic symptoms, nearly three-fourths of the patients were found normal on endoscopy.[10] The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 58% in this study with the prevalence of H. pylori infection being 93% in patients with peptic ulcers. Positive endoscopy findings were noted in the majority of our patients with dyspepsia. A high prevalence of H. pylori infection (93%) is a potential reason for such high yield on endoscopy. However, the role of the peculiar indigenous dietary factors and demographics need further investigation.

Endoscopic lesions found in the current study are noteworthy. We observed esophagitis, gastritis and duodenitis rather than ulcerative or erosive lesions. This is in contrast to the other studies mentioned above, where ulcers or erosions predominated.[8-10] Antral nodularity was reported to have a high specificity of 95 to 100% for H. pylori infection in children and adults. However its sensitivity has been reported to vary from 28 to 74%.[11-18] Similar nodular gastritis has been noticed in ~18% of our patients who also had a high rate of H. pylori infection (93%).

The incidence of H. pylori infection was higher in the current study not only in comparison to studies from Canada[8] and Italy[10] but also from south India.[9] The epidemiological divide between the industrialized nations and the developing countries with regards to living conditions and socioeconomic conditions can explain the higher incidence of H. pylori in the current study. However the higher infection rates compared to studies from south India[9] suggest other factors such as altitude, local dietary practices at play. Such high rates of H. pylori infection at high altitudes in comparison to coastal areas was also reported from Peru.[4] High salt intake was found to enhance H. pylori colonization[19] and synergize H. pylori induced damage to the gastric mucosa[20] in animal models. High salt diet was also found to increase the risk of H. pylori infection in a Japanese study.[21] Certain high salt diets form an important part of the local cuisine of Ladakh region and a majority of our patients were partaking these.

Discussion

Given the lack of correlation between clinical, endoscopic and histopathology findings in dyspeptic patients, gastritis poses a great diagnostic dilemma for gastroenterologists. Often these patients get clubbed with patients having markedly different presentations and investigation findings. With the discovery of H. pylori in 1982, chronic gastritis was proposed to be caused by repeated inflammatory insults to the gastric mucosa and subsequent atrophy because of incited by the infection. The updated Sydney System helps in making a more objective assessment of this condition.[6]

Epigastric pain, heartburn, regurgitation, bloating, nocturnal pain, belching, discomfort after meals, early satiety, nausea, postprandial fullness are usual presentations in dyspeptic patients with epigastric pain being the most common.[7] Pain radiating to the back is not a symptom usually reported in these patients. Such symptoms are characteristic of pancreatitis or penetrating peptic ulcer disease. However in the Ladakhi gastritis patients we examined besides epigastric pain, heartburn and regurgitation, pain radiating to the back was a unique presentation noted in nearly half of the subjects. Clinically significant endoscopy findings have been previously noted in 58% of 1040 patients presenting with dyspeptic symptoms to a primary care establishment in Canada.[8] An endoscopy finding of just gastritis was not considered as sufficient evidence in this study and only erosions, ulcers, Barrett’s esophagus, reflux esophagitis were considered clinically significant. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was 30%. In a study of 197 Tibetan patients with dyspeptic symptoms from South India, endoscopic evidence of ulcers, present or previous, was found in 18% of the patients; evidence of gastritis or duodenitis was found in 30% and H. pylori was positive in 77%.[9] In a community based study from Italy involving 1033 patients with or without dyspeptic symptoms, nearly three-fourths of the patients were found normal on endoscopy.[10] The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 58% in this study with the prevalence of H. pylori infection being 93% in patients with peptic ulcers. Positive endoscopy findings were noted in the majority of our patients with dyspepsia. A high prevalence of H. pylori infection (93%) is a potential reason for such high yield on endoscopy. However, the role of the peculiar indigenous dietary factors and demographics need further investigation.

Endoscopic lesions found in the current study are noteworthy. We observed esophagitis, gastritis and duodenitis rather than ulcerative or erosive lesions. This is in contrast to the other studies mentioned above, where ulcers or erosions predominated.[8-10] Antral nodularity was reported to have a high specificity of 95 to 100% for H. pylori infection in children and adults. However its sensitivity has been reported to vary from 28 to 74%.[11-18] Similar nodular gastritis has been noticed in ~18% of our patients who also had a high rate of H. pylori infection (93%).

The incidence of H. pylori infection was higher in the current study not only in comparison to studies from Canada[8] and Italy[10] but also from south India.[9] The epidemiological divide between the industrialized nations and the developing countries with regards to living conditions and socioeconomic conditions can explain the higher incidence of H. pylori in the current study. However the higher infection rates compared to studies from south India[9] suggest other factors such as altitude, local dietary practices at play. Such high rates of H. pylori infection at high altitudes in comparison to coastal areas was also reported from Peru.[4] High salt intake was found to enhance H. pylori colonization[19] and synergize H. pylori induced damage to the gastric mucosa[20] in animal models. High salt diet was also found to increase the risk of H. pylori infection in a Japanese study.[21] Certain high salt diets form an important part of the local cuisine of Ladakh region and a majority of our patients were partaking these.

H. pylori associated chronic gastritis can manifest either as antral- or corpus-predominant gastritis with multifocal atrophy. The former predisposes the patient to development of duodenal ulcers and the latter to gastric ulcers and gastric carcinoma.[22] Thus any histology findings of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are important. The risk of developing atrophy and metaplasia were found to be different among different ethnic populations. Atrophic changes were detected in 60% of mainstream Bengalis with duodenal ulcers and H. pylori infection, most of them being mild. In contrast, atrophic changes were detected in only 28% of asymptomatic ethnic tribals with H. pylori from the same part of India.[23] In a study from Iran, gastric mucosal atrophy was found in 67% of patients and intestinal metaplasia in 44% of patients with H. pylori infection, the majority of them being more than 60 years of age.[24] In a study of H. pylori positive Japanese adults aged less than 29 years, atrophy was found in about 28% of antral and corpus biopsies.[15] In Peru where the infection rate of H. pylori is high, moderate or severe chronic atrophic gastritis was found in 67% of patients with dyspepsia.[25] The severity of the histologic lesions was also found to be worse in patients living at higher altitudes.[5] In the current study atrophy was observed in 90% of the biopsies. Although the majority of the biopsies showed mild atrophy and intestinal metaplasia was observed in only 19% of the biopsies, the prevalence of atrophic gastritis is definitely higher than that reported from the plains or plateau regions.

H. pylori and non-Helicobacter bacteria were found to have synergistic effect on the development of atrophic gastritis.[26] A high prevalence of about 65% of non-H. pylori bacterial colonization of the gastric mucosa was found concurrently with H. pylori infection in a study from China. The microorganisms most commonly isolated included upper respiratory tract flora.[27] In the current study, other bacteria were isolated in all 15 patients subjected to random gastric/duodenal aspirate cultures. However, the flora isolated included Gram negative bacilli including E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp. Acid suppressive agents prescribed to these patients for dyspepsia and hypochlorhydria related to H. pylori infection could be contributing the bacterial growth seen. However, the predominance of select Gram-negative flora in comparison to upper respiratory tract flora as previously observed,[27,28] cannot be unexplained.

In conclusion, dyspepsia at high altitude commonly presents as pain radiating to the back with very high (90%) H. pylori infection rates. Endoscopy findings of antral and nodular and atrophic gastritis are common. Concomitant gastric colonization with select Gram-negative flora was also observed. Whether these atrophic changes worsen with age and undergo carcinogenesis, associated with a higher prevalence of gastric cancer, needs further studies in this population. Given the findings from high-altitude regions of Peru[4,5] and the understanding that high salt intake synergizes the deleterious effects of H. pylori on gastric mucosa,[19-21] further examination of the unique microbiology and clinical epidemiology of these high-altitude populations is needed.

References

- Wallander MA, Johansson S, Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jones R. Dyspepsia in general practice: incidence, risk factors, comorbidity and mortality. Fam Pract. 2007;24:403–11.

- Owen DA. Gastritis and carditis. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:325–41.

- Singh V, Trikha B, Nain CK, Singh K, Vaiphei K. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer in India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:659–65.

- Ecology of Helicobacter pylori in Peru: infection rates in coastal, high altitude, and jungle communities. The Gastrointestinal Physiology Working Group of the Cayetano Heredia and the Johns Hopkins University. Gut. 1992;33:604–5.

- Recavarren-Arce S, Ramirez-Ramos A, Gilman RH, Chinga-Alayo E, Watanabe-Yamamoto J, Rodriguez-Ulloa C, et al. Severe gastritis in the Peruvian Andes. Histopathology. 2005;46:374–9.

- Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–81.

- Meineche-Schmidt V. Classification of dyspepsia and response to treatment with proton-pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1171–9.

- Thomson AB, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Chiba N, White RJ, Daniels S, et al. The prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian Adult Dyspepsia Empiric Treatment - Prompt Endoscopy (CADET-PE) study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1481–91.

- Katelaris PH, Tippett GH, Norbu P, Lowe DG, Brennan R, Farthing MJ. Dyspepsia, Helicobacter pylori, and peptic ulcer in a randomly selected population in India. Gut. 1992;33:1462–6.

- Zagari RM, Law GR, Fuccio L, Pozzato P, Forman D, Bazzoli F. Dyspeptic symptoms and endoscopic findings in the community: the Loiano-Monghidoro study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:565–71.

- Labenz J, Gyenes E, Ruhl GH, Wieczorek M, Hluchy J, Borsch G. [Is Helicobacter pylori gastritis a macroscopic diagnosis?]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1993;118:176–80.

- Laine L, Cohen H, Sloane R, Marin-Sorensen M, Weinstein WM. Interobserver agreement and predictive value of endoscopic findings for H. pylori and gastritis in normal volunteers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:420–3.

- Grellier L, Tanner P, Grainger SL. Antral nodularity: Macroscopic marker for Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. I993;34:S35.

- Sbeih F, Abdullah A, Sullivan S, Merenkov Z. Antral nodularity, gastric lymphoid hyperplasia, and Helicobacter pylori in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:227–30.

- Kamada T, Sugiu K, Hata J, Kusunoki H, Hamada H, Kido S, et al. Evaluation of endoscopic and histological findings in Helicobacter pylori-positive Japanese young adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:258–61.

- Bujanover Y, Konikoff F, Baratz M. Nodular gastritis and Helicobacter pylori. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1990;11:41–4.

- Hassall E, Dimmick JE. Unique features of Helicobacter pylori disease in children. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:417–23.

- Khan MQ, Alhomsi Z, Al-Momen S, Ahmad M. Endoscopic features of Helicobacter pylori induced gastritis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:9–14.

- Fox JG, Dangler CA, Taylor NS, King A, Koh TJ, Wang TC. High-salt diet induces gastric epithelial hyperplasia and parietal cell loss, and enhances Helicobacter pylori colonization in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4823–8.

- Gamboa-Dominguez A, Ubbelohde T, Saqui-Salces M, Romano- Mazzoti L, Cervantes M, Dominguez-Fonseca C, et al. Salt and stress synergize H. pylori-induced gastric lesions, cell proliferation, and p21 expression in Mongolian gerbils. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1517–26.

- Tsugane S, Tei Y, Takahashi T, Watanabe S, Sugano K. Salty food intake and risk of Helicobacter pylori infection. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85:474–8.

- Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–86.

- Saha DR, Datta S, Chattopadhyay S, Patra R, De R, Rajendran K, et al. Indistinguishable cellular changes in gastric mucosa between Helicobacter pylori infected asymptomatic tribal and duodenal ulcer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1105–12.

- Emami MH, Taheri H, Tavakoli H, Esmaeili A. Are endoscopic findings predictive for the presence of H. pylori infection? What about indirect histologic findings? J Res Med Sci. 2007;12:80–5.

- Recavarren-Arce S, Gilman RH, Leon-Barua R, Salazar G, McDonald J, Lozano R, et al. Chronic atrophic gastritis: early diagnosis in a population where Helicobacter pylori infection is frequent. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1006–12.

- Sanduleanu S, Jonkers D, De Bruine A, Hameeteman W, Stockbrugger RW. Double gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori and non-Helicobacter pylori bacteria during acidsuppressive therapy: increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines and development of atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1163–75.

- Hu Y, He LH, Xiao D, Liu GD, Gu YX, Tao XX, et al. Bacterial flora concurrent with Helicobacter pylori in the stomach of patients with upper gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1257–61.

- Husebye E. The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth. Chemotherapy. 2005;51 Suppl 1:1–22.

|

|

|

|

|

|