Ashwin Rammohan, Jeswanth Sathyanesen, Ravichandran Palaniappan, G Manoharan

Institute of Surgical Gastroenterology and Liver Transplantation,

Centre for GI Bleed,

Division of HPB Diseases, Stanley Medical College Hospital, Old

Jail Road, Chennai, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Ashwin Rammohan

Email: ashwinrammohan@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.207

48uep6bbphidvals|631 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Liver involvement in tuberculosis, although common in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis, is usually clinically silent.[1] Isolated macronodular hepatic tuberculosis is the rarest form of hepatic tuberculosis.[1,2] Although the incidence of tuberculosis had initially decreased with the advent of effective chemotherapy, it is currently increasing especially among the elderly, the immunocompromised and those from the lower socioeconomic strata.[3] Diagnosis of nodular hepatic tuberculosis is not straightforward, especially in the absence of pulmonary /miliary tuberculosis as this lesion is a tumour mimic on imaging.[1,2] The diagnosis of macronodular tuberculosis is usually unsuspected and confused with primary or metastatic carcinoma and as in our case, it may necessitate a hepatic resection.

Case report

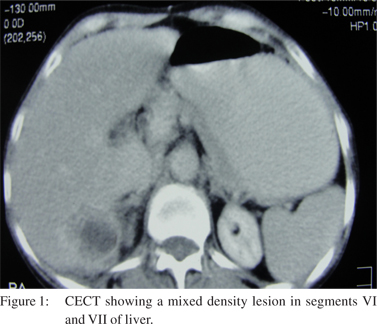

A 50-year-old female presented with complaints of upper abdominal pain for one month and low grade pyrexia for 10 days. She also complained of anorexia and significant weight loss. She had no comorbid illnesses and no past or family history of contact with tuberculosis. At presentation she was thin and anicteric. Her general and abdominal examination were unremarkable and her vitals were stable. Her complete hemogram was within normal limits, apart from a raised ESR of 40 mm/hr and her liver function tests were within normal limits. The serum á-fetoprotein was 2.31 ng/mL (normal range 0–9.0 ng/mL) and carcinoembryonic antigen was 1.47 ng/mL (normal range 0–3.0 ng/mL). Viral markers for hepatitis B and C were also negative. The chest X-ray showed no obvious abnormalities. Ultrasonography showed a solid-appearing, confluent, irregular, hypoechoic mass lesion in segments VI and VII of the right hepatic lobe, measuring 7×5 cm, with evidence of flow within the lesion. Contrast-enhanced CT showed a 7×4 cm, mixed density lesion in segments VI and VII.Peripheral enhancement with central non-enhancing areas after intravenous injection of contrast in the arterial phase with persistent opacification in venous and delayed phases was noticed (Figure 1). Her esophagoduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were normal. Since the diagnosis was inconclusive, we performed a fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of the lesion which also gave inconclusive results.

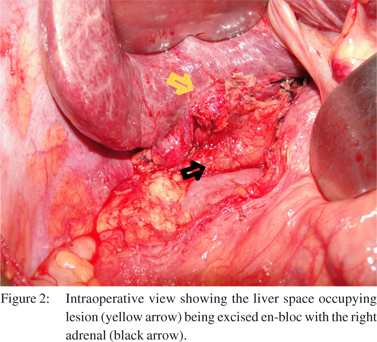

Therapeutic options were discussed with the patient and she was offered surgery. She underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy which revealed a cirrhotic liver, with left lobe atrophy and a compensatory right lobe hypertrophy. The space occupying lesion (SOL) was noted in segments VI and VII of the liver and was found adherent and infiltrating the right adrenal gland. The right kidney was free. Since the patient had cirrhosis and we made a provisional preoperative diagnosis of a malignant liver SOL. A wedge resection of the liver lesion was performed with a 2 cm three dimensional margin and an en-bloc right adrenalectomy (Figure 2). Ex-vivo aspirate of the specimen revealed acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on Ziehl Neelsen staining. Histopathology revealed multiple caseating granulomata bordered by multinucleate giant cells. The surrounding liver parenchyma showed lymphocytic infiltration within the portal tracts with occasional eosinophils. These findings were consistent with hepatic tuberculosis. Her postoperative period was uneventful and she was discharged on the 6th postoperative day. She was started on quadruple anti-tuberculosis therapy and is asymptomatic on follow-up, tolerating her medication well.

Discussion

Liver is a rare site for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis of the liver has been classified into six different types namely liver involvement in miliary tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis with liver involvement, primary liver tuberculosis, focal tuberculoma, tuberculous abscess and tuberculous cholangitis.[4] Isolated giant solid macronodular tuberculosis (tuberculoma of liver) with no clinical extrapulmonary manifestations is the rarest form.[1,2,4] Hepatic tuberculosis with mass lesions larger than 2 mm in diameter are referred to as macronodular or pseudotumoural tuberculosis.[4,5] The presentation can be protean, with nonspecific abdominal pain, fever and weight loss being the most common symptoms. Clinical signs are nonspecific and hepatomegaly may be the only abdominal sign in this condition.[2,5,6] Biochemical studies reveal no consistent findings, raised serum alkaline phosphatase levels have been the frequently noted.

Discussion

Liver is a rare site for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis of the liver has been classified into six different types namely liver involvement in miliary tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis with liver involvement, primary liver tuberculosis, focal tuberculoma, tuberculous abscess and tuberculous cholangitis.[4] Isolated giant solid macronodular tuberculosis (tuberculoma of liver) with no clinical extrapulmonary manifestations is the rarest form.[1,2,4] Hepatic tuberculosis with mass lesions larger than 2 mm in diameter are referred to as macronodular or pseudotumoural tuberculosis.[4,5] The presentation can be protean, with nonspecific abdominal pain, fever and weight loss being the most common symptoms. Clinical signs are nonspecific and hepatomegaly may be the only abdominal sign in this condition.[2,5,6] Biochemical studies reveal no consistent findings, raised serum alkaline phosphatase levels have been the frequently noted.

Tuberculous cholangitis may present with obstructive jaundice due to enlarged lymph nodes. Others findings may include anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, and hyponatraemia.[2,5,6] On the basis of imaging alone, these lesions are indistinguishable from other neoplastic lesions of the liver. Imaging techniques (ultrasonography, CT and MRI) are useful in diagnosing tuberculoma or tubercular abscess. On CECT, they appear as non-enhancing, central, low density lesions due to the caseation necrosis with a slightly enhancing peripheral rim due to the surrounding granulation tissue. When multiple, these lesions typically show varying densities due to the coexistence of different stages of granuloma formation, liquefaction, necrosis, fibrosis and calcification.[4,7] On MRI these lesions appear as a hypointense nodule with a hypointense rim on T1- weighted imaging and a hypointense, isointense or hyperintense lesion with a less intense rim on T2-weighted imaging with peripheral enhancement.[4,7] Aspirates from the lesion for AFB staining have shown a sensitivity of 0-45%, while cultures are positive in only 10 to 60% cases. With a sensitivity of 57% the results of polymerase chain reaction have also been disappointing.[3,8] Pathological examination is necessary for diagnosis.[1,2,5,6] Histologically, the presence of a caseating granuloma is diagnostic of hepatic tuberculosis.[2,5]

Quadruple therapy (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) is recommended because of the increasing incidence of drug-resistant tuberculosis. A one year course of therapy is recommended.[2,3,5,6] With early diagnosis and effective treatment, the prognosis of hepatic tuberculosis is usually good.[2,6]

Conclusion

Tuberculosis presenting as an isolated liver tumour, without active pulmonary or miliary tuberculosis or other evidence of tuberculosis is distinctly rare. These lesions are easily confused with more sinister liver neoplasms. Hence the need for increased awareness of these tumour mimics, particularly in endemic areas, to avert unnecessary morbidity from surgery.

References

- Vimalraj V, Jyotibasu D, Rajendran S, Ravichandran P, Jeswanth S, Balachandar TG, et al. Macronodular hepatic tuberculosis necessitating hepatic resection: a diagnostic conundrum. Can J Surg. 2007;50:E7–8.

- Desai CS, Josh AG, Abraham P, Desai DC, Deshpande RB, Bhaduri A, et al. Hepatic tuberculosis in absence of disseminated abdominal tuberculosis. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:41–3.

- Hsieh TC, Wu YC, Hsu CN, Yang CF, Chiang IP, Hsieh CY, et al. Hepatic macronodular tuberculoma mimics liver metastasis in a patient with locoregional advanced tongue cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e641–3.

- Levine C. Primary macronodular hepatic tuberculosis: US and CT appearances. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:307–9.

- Mert A, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Ozturk R, Bilir M. Localized hepatic tuberculosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14:511–2.

- Huang WT, Wang CC, Chen WJ, Cheng YF, Eng HL. The nodular form of hepatic tuberculosis: a review with five additional new cases. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:835–9.

- Yu RS, Zhang SZ, Wu JJ, Li RF. Imaging diagnosis of 12 patients with hepatic tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1639–42.

- Diaz ML, Herrera T, Lopez-Vidal Y, Calva JJ, Hernandez R, Palacios GR, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in tissue and assessment of its utility in the diagnosis of hepatic granulomas. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;127:359–63.

|