|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Jeyamani Ramachandran1, Marcus Teo2,3, Richard Kimber4, Alan J Wigg2,3

Department of Hepatology,1

Christian Medical College,

Vellore, India

Hepatology and Liver Transplant Medicine Unit,2 and

South Australian Liver Transplant Unit,3

Flinders Medical Centre,

Adelaide, South Australia

Department of Gastroenterology,4

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

Adelaide, South Australia

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Jeyamani Ramachandran

Email: jeyapati@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.166

48uep6bbphidvals|669 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Successful management of liver transplantation for hepatitis B (HBV) involves avoidance of reinfection.The high cost associated with hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIg)prophylaxis can be minimized with low dose intramuscular HBIg regimens along with lamivudine.[1] But in patients with high viral load, this regimen has been associated with HBV recurrences.[1] In this report we describe a successful liver transplantation during a HBV flare after discontinuation of prolonged entecavir prophylaxis for lymphoma chemotherapy andsuccessful treatment of early graft re-infection using a combination ofentecavirand tailored low dose HBIg therapy aided by quantitative HBsAg testing.

Case report

Our patient was a 65-year-old woman with HBeAg negative chronic HBV infection with high viral load (785,000 IU/ml). She had consistently normal liver function tests (LFT) and normal liver ultrasound findings. She developed early stage (1A) Burkitt-like high grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Entecavir was commenced at 0.5 mg/dayprior to chemo-radiotherapy. Chemotherapy comprised of a hyper-CVAD regimen (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone) which was given for five months, and was followed by radiotherapy.She achieved complete remission.She was continued on entecavirwith undetectable HBV DNA levels and normal LFTs for further 14 months after chemoradiotherapy.

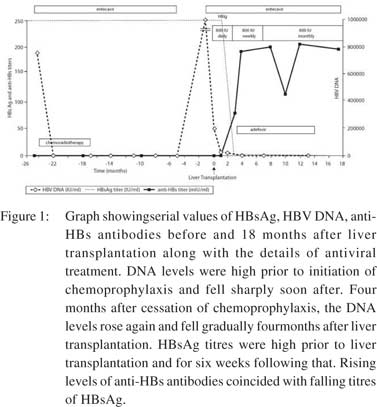

Liver biopsy at this time showed minimal inflammatory activity and Scheuer fibrosis score-1. Entecavir was stopped 14 months after chemo-radiotherapy. Four and a half months later, she presented with clinical and biochemical flare related to reactivation of HBV. Viral loads rose to >100 million IU/ml and LFT were as follows: serum bilirubin 139 µmol/l; AST 638 U/L; ALT 643 U/L; and INR 3.1. She developed encephalopathy and was referred to our institution for urgent liver transplantwith a Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 28 and entecavir restarted at 1mg/day.The remission status and low recurrence risk of lymphoma were confirmed with the treating oncologist before undertaking transplant. Entecavir was given for a total eight days prior to transplant. However, the patient remained HBV DNA positive with a viral load of205,000 IU/ml at the time of liver transplant. The explant liver showed sub-massive necrosis with early nodular regeneration. She received 800IU of HBIg intramuscularly during the an hepatic phase followed by 800IU daily after transplant along with daily entecavir. Despite this, she remained persistently HBsAg and HBV DNA positive with absent anti-HBs antibodies. She was on tacrolimus, azathioprine and steroids as per the unit protocol. She maintained normalliver function tests during the entire follow up period. Monitoring of HBsAg titres revealed persistently high concentration in the post-transplant period up to five weeks, followed by a significant decline thereafter. HBIg was given daily for six weeks and reduced to 800IU weekly upto 16 weeks. A gradual rise in the anti-HBs titre was observed at the beginning of week six post-transplant and increased to 88mIU by week 12. HBsAg clearance was achieved by week 12 and it sustained thereafter. HBV DNA levels slowly declined and became negative after four months. The patient has currently reached 18 months post-transplant and remains HBsAg and HBV DNA negative with normal LFT and is on entecavirand HBIG 800IU monthly. Adefovir was added at week seven posttransplantbut discontinued at 14 months due to worsening serum creatinine. Changes in HBV DNA, HBsAg and anti-HBs titres and their association with clinical events are depicted in Figure 1.

HBV sequence analysis of the polymerase region revealed genotype B with no mutations forentecavir, adefoviror lamivudine resistance. Analysis of the HBV precore region revealed a mutation at start codon (M1T), associated with no HBeAg synthesis and HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B.

Discussion

While reinfections from extrahepatic sources of HBV may occur any time post-transplant, early reinfections are frequently due to the high concentration of circulating HBV particles. This happens when the tire of anti-HBs antibodies is insufficient to neutralize circulating HBsAgparticles.[2]

Failure of low dose intramuscular HBIg in combination with lamivudine1is usually associated with high pre-transplant viral load.[1]Our patient had high pre-transplant HBV DNA load, which is a well described risk factor for post-transplant recurrence of hepatitis B.[3]Instead of the standard protocol adopted in our south Australian liver transplant unit, wherein HBIg therapy is given daily only for the initial seven days, his patient was given six weeks of daily HBIg. Frequent quantitative monitoring of HBsAg, anti-HBs and HBV DNA titres provided valuable guidance. Monitoring of qualitative HBsAg alone cannot differentiate between an established recurrent hepatitis or a slowly resolving early recurrence. The combination of gradually rising anti HBs titers together with falling HBsAg and HBV DNA preceded HBsAg clearance. Several pre-core and promoter region mutations have been associated with reactivation of HBV in patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy[4] and we do not know the exact role of the M1T mutation in this case.

HBV sequence analysis of the polymerase region revealed genotype B with no mutations forentecavir, adefoviror lamivudine resistance. Analysis of the HBV precore region revealed a mutation at start codon (M1T), associated with no HBeAg synthesis and HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B.

Discussion

While reinfections from extrahepatic sources of HBV may occur any time post-transplant, early reinfections are frequently due to the high concentration of circulating HBV particles. This happens when the tire of anti-HBs antibodies is insufficient to neutralize circulating HBsAgparticles.[2]

Failure of low dose intramuscular HBIg in combination with lamivudine1is usually associated with high pre-transplant viral load.[1]Our patient had high pre-transplant HBV DNA load, which is a well described risk factor for post-transplant recurrence of hepatitis B.[3]Instead of the standard protocol adopted in our south Australian liver transplant unit, wherein HBIg therapy is given daily only for the initial seven days, his patient was given six weeks of daily HBIg. Frequent quantitative monitoring of HBsAg, anti-HBs and HBV DNA titres provided valuable guidance. Monitoring of qualitative HBsAg alone cannot differentiate between an established recurrent hepatitis or a slowly resolving early recurrence. The combination of gradually rising anti HBs titers together with falling HBsAg and HBV DNA preceded HBsAg clearance. Several pre-core and promoter region mutations have been associated with reactivation of HBV in patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy[4] and we do not know the exact role of the M1T mutation in this case.

A further interesting aspect of this case is the HBV reactivation following cessation of prolonged antiviral prophylaxisfor non-rituximab based chemotherapy. Reactivation of HBV is a well-recognized complication in HBsAg positive patients who receive cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy[5] and may lead to fulminant hepatic failure in some patients,[6] but the optimal duration of prophylaxis remains controversial. Current European guidelines recommend antiviral prophylaxis for 12 months following chemotherapy.[7]Recent American and Australian Society guidelines recommendpatients with high baseline HBV DNA (>2,000 IU/ml) to continue prophylaxis until they reach treatment end points for chronic hepatitis.[8]It is clear from this case that even prolonged prophylaxis does not protect against withdrawal flares in some settings. It is also very important to perform frequent ALT and viral load testing after cessation of antiviral therapy to detect early flares.

In summary, we have presented here a case where frequent quantitative monitoring of HBsAg, anti-HBs and HBV DNA helped in optimising post-transplant HBV prophylaxis.This is a unique case of successful liver transplant for HBV reactivation precipitated by cessation of prolonged HBV prophylaxis forchemotherapy. We recommend lifelong continuation of antiviral prophylaxis following chemotherapy in patients with high baseline viral load.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful advice and sequencing data provided by Professor Stephen Locarnini and Dr Scott Bowden from the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, North Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. We also acknowledge helpful advice from Dr PietroLampertico (University of Milan, Italy), Graham Foster (St Barts Hospital, London, England) and Professor Elwyn Elias (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England). The authors acknowledge the assistance provided by Julie Caddy, Medical Illustration and Media, Flinders Medical Centre, Adelaide, in making the graph for this manuscript.

References

- Gane EJ, Angus PW, Strasser S, Crawford DH, Ring J, Jeffrey GP, et al. Lamivudine plus low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin to prevent recurrent hepatitis B following liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:931–7.

- Terrault N, Roche B, Samuel D. Management of the hepatitis B virus in the liver transplantation setting: a European and an American perspective. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:716–32.

- Samuel D, Muller R, Alexander G, Fassati L, Ducot B, Benhamou JP, et al. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842–7.

- Dai MS, Lu JJ, Chen YC, Perng CL, Chao TY. Reactivation of precore mutant hepatitis B virus in chemotherapy-treated patients. Cancer. 2001;92:2927–32.

- Xunrong L, Yan AW, Liang R, Lau GK. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation after cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy—pathogenesis and management. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11:287–99.

- Hsu C, Hsiung CA, Su IJ, Hwang WS, Wang MC, Lin SF, et al. A revisit of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:844–53.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–42.

- Gastroenterological Society of Australia. Australian and New Zealand chronic hepatitis B (CHB) recommendations. 1st ed.Sydney: Digestive Health Foundation; 2008.

|

|

|

|

|

|