|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy, postoperative pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, International study group definitions |

|

|

citalopram and alcohol withdrawal can you drink alcohol while taking citalopram seankearney.com

Department of Surgical

Gastroenterology,

Medical College, Trivandrum,

Kerala - 695011, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. VA Iyoob

Email: iyoobali@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.161

Abstract

Background and aim: Though, the morbidity following pancreatoduodenectomy remains high the mortality rate has reduced to <5% in many high volume centres. The aim of this prospective study was to quantify the complications following pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy using international definitions and to prove that pylorus preservation and retrocolic duodenojejunostomy are not associated with increased incidence of delayed gastric emptying.

Methods: This was a prospective observational study at a single GI surgery referral unit, conducted from January 2010 to December 2012. Patients who underwent pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy for various indications were included; barring those who underwent major surgical procedures along with pancreatoduodenectomy.

Results: 76 patients (M:F = 37:39) underwent pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy during the study period; with median age 52 yrs (range: 29-83) and hospital stay 11 days (range: 8-50). Overall mortality and significant morbidity were 7.89% and 12.5%, respectively. Four patients each (5.26%) developed significant delayed gastric emptying (DGE) and pancreatic fistula. Presence of comorbidity (p=0.019; odds ratio: 3.16) and periampullary tumours (p=0.011; odds ratio: 7.91) were identified as risk factors for the development of complications. Pancreatic juice amylase levels in chronic pancreatitis were very low (p<0.005).

Conclusion: Pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy can be performed with very low mortality and morbidity at high volume centres. DGE is not significantly increased with pylorus preservation and retrocolic duodenojejunostomy, and is often secondary to post-op complications. The International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) definition may miss pancreatic fistula in chronic pancreatitis.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|664 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Although the mortality rates after pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) have significantly come down over the last few decades, the associated morbidity continues to be high at many pancreatic surgery units across the world. This drastic reduction in mortality owes its gratitude to a number of factors besides improved surgical technique like advancements in anaesthesia, postoperative care, imaging and interventional technology. Pancreatic fistula (PF) still constitutes the major postoperative complication (5-30%) and also the commonest denominator that leads to most post-PD sequelae such as delayed gastric emptying (DGE), haemorrhage, wound infection, intraperitoneal collections, prolonged drainage, extended hospital stay, reoperations, death and high treatment cost. The newly proposed international definitions of major complications after pancreatic resection should allow better validation of different pancreatic surgery techniques. PD is one of the more common surgical procedures that we perform at our unit and 90% of our PD is pylorus preserving (ppPD). Since the introduction of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) and International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definitions for postoperative complications, we planned to conduct a prospective study to assess the postoperative morbidity following our technique of ppPD and to assess the impact of pylorus preservation and retrocolic duodenojejunostomy (DJ) on the incidence of DGE. This assessment has become all the more important due to conflicting reports of their influence on gastric emptying.

Methods

This prospective observational study examined patients who underwent PD from January 2010 to December 2012 at our surgical gastroenterology unit. Patients undergoing major surgical procedures along with PD and those undergoing PD other than pylorus preserving surgery (ppPD) were excluded from the study.

Operative technique

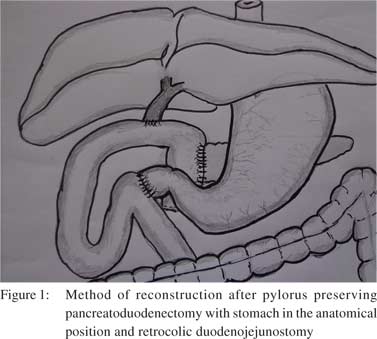

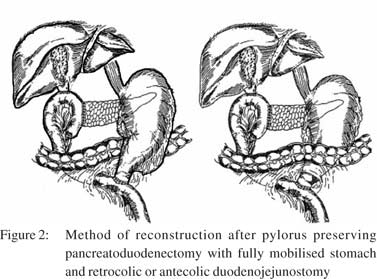

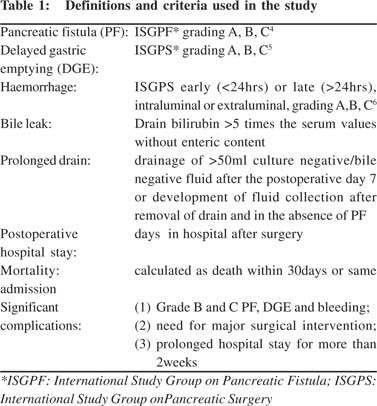

The procedure of ppPD was similar in all cases in terms of dissection and reconstruction. We did not mobilize the gastrohepatic omentum, so as to keep the intact right gastric pedicle and stomach in the anatomical position. Standard peripancreatic lymph node dissection was done.[1] Hepatic artery nodes were approached from behind the stomach. The uncinate process was divided flush with the superior mesenteric artery. The retroperitoneal and other cut margins were marked with sutures for easy identification during histopathology examination. Reconstruction starts with pancreato-jejunostomy (PJ) as described below. A patch of serosa corresponding to the cross-section of pancreas is removed 2-3 cm from the closed jejunal end. [4-8] polygalactin (4-o to 6-o) pancreatic ductal sutures are placed simultaneously all around. Then posterior sero-capsular sutures are completed with 3-o black silk. Now the posterior ductal sutures are threaded from the mucosal aspect of jejunum and tied, followed by anterior duct to mucosa sutures. Anterior sero-capsular suturing completes PJ. Endto- side hepatico-jejunostomy (HJ) is constructed 8-10 cm distal to PJ with interrupted full thickness 4-o polygalactin followed by end-to-side duodenojejunostomy (DJ) 20-30 cm distal to HJ with single layer extra-mucosal 3-o black silk sutures. All these reconstructions are performed on the remnant jejunum via the retrocolic route (Figure 1). No magnification devices are used routinely. Since the stomach is kept in the normal anatomical position, only the jejunal loop is taken through transverse mesocolon unlike other retrocolic reconstructions described elsewhere (Figure 2).[2] Given the high incidence of pancreatic cancer in patients with TCP,[3] they also undergo the same procedure when surgery is indicated for a pancreatic head mass with suspected or proven malignancy. We routinely perform feeding jejunostomy (FJ) using a 10 Fr infant feeding tube and this route is not used unless oral feeding is contraindicated as per the protocol. This avoids the need for parenteral nutrition (PN) if the oral route is limited by the onset of DGE. Besides common demographic profiles, the details of morbidity, mortality, post-op stay, drain output, amylase values in the serum, drain fluid and pancreatic juice were recorded. Definitions and criteria that were used for assessing post-op sequelae are shown in Table 1.[4,5,6] Patients with diabetes of more than 10 years duration were also excluded while analyzing DGE. The nasogastric tube (NGT) was removed when the aspirate reduced below 400 ml with progressively improving bowel sounds. A 100 µg octreotide injection is given at the time of induction if a soft pancreas and small duct is expected or else it’s given intraoperatively and continued for five days postoperatively. Abdominal drains were removed when the drain fluid reduced below 30 ml and showed low amylase levels. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from our Institutional Ethical Committee.

Data analysis

For normally distributed variables, data were presented as mean ± SD; t test was used to compare means. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as medians with range and non-parametric tests were employed for statistical comparison. The Chi-square test was used for nominal data and Fisher’s exact test was used for instances with smaller expected data frequency. Plausible risk factors were elucidated using logistic regression analysis and the incidence of surgical complication was considered as a dichotomous dependent variable. Odds ratios are reported for significant variables.

Results

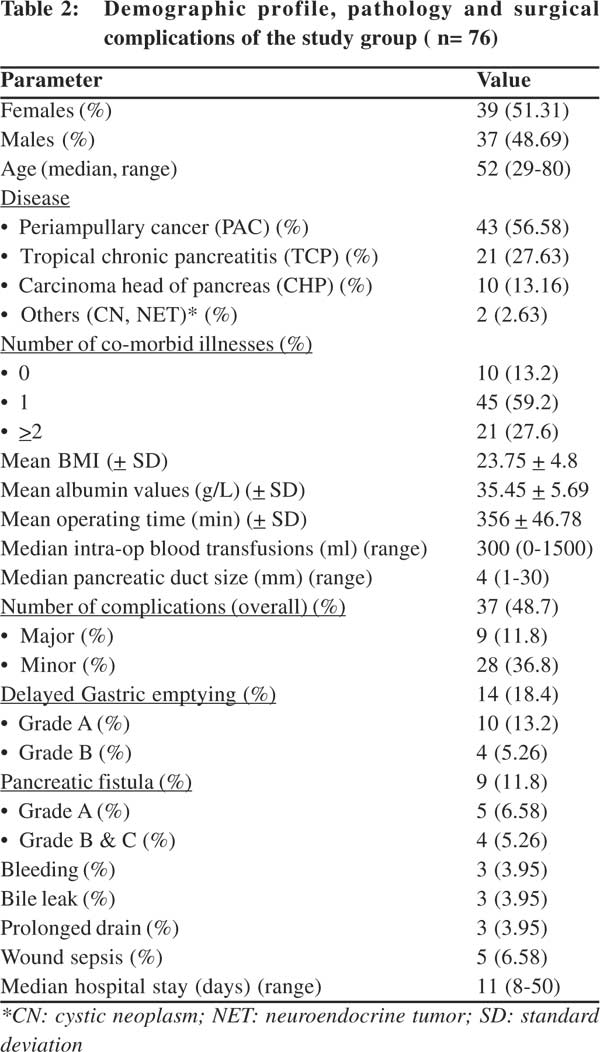

A total of 76 patients satisfying all inclusion and exclusion criteria were analysed in detail. Their demographic profile, intraoperative parameters and postoperative complications are summarized in Table 2. Six patients died postoperatively contributing an overall mortality rate of 7.89%. Cause of death included postoperative complications in two including PF in one and sepsis in another, besides adverse cardiac events in remaining four patients. Nine (12.5%) patients developed major postoperative complications while minor complications were noted in 28 (38.89%) patients. DGE and PF were seen in four patients each. One patient required re-operation for early extraluminal haemorrhage (ISGPS grade B) and recovered without any further adverse events.

Data analysis

For normally distributed variables, data were presented as mean ± SD; t test was used to compare means. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as medians with range and non-parametric tests were employed for statistical comparison. The Chi-square test was used for nominal data and Fisher’s exact test was used for instances with smaller expected data frequency. Plausible risk factors were elucidated using logistic regression analysis and the incidence of surgical complication was considered as a dichotomous dependent variable. Odds ratios are reported for significant variables.

Results

A total of 76 patients satisfying all inclusion and exclusion criteria were analysed in detail. Their demographic profile, intraoperative parameters and postoperative complications are summarized in Table 2. Six patients died postoperatively contributing an overall mortality rate of 7.89%. Cause of death included postoperative complications in two including PF in one and sepsis in another, besides adverse cardiac events in remaining four patients. Nine (12.5%) patients developed major postoperative complications while minor complications were noted in 28 (38.89%) patients. DGE and PF were seen in four patients each. One patient required re-operation for early extraluminal haemorrhage (ISGPS grade B) and recovered without any further adverse events.

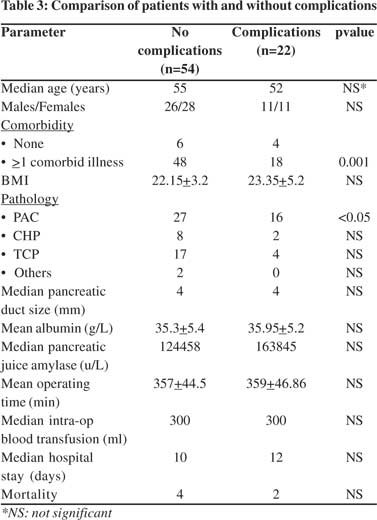

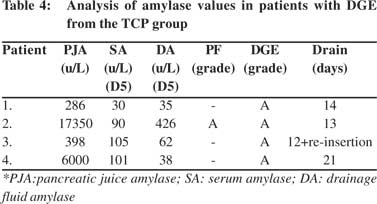

Subgroup analysis of patients with and without complications is shown in Table 3. Twenty-one patients were suffering from tropical chronic pancreatitis (TCP) which is well known to influence onset of PF by nature of its pathophysiology. So we further compared patients with (n=21) and without (n=55) TCP. This subgroup analysis showed increased incidence of DM, larger pancreatic duct size, lower pancreatic juice amylase levels and lower rates of major morbidity among TCP patients (Table 4). The two groups showed no significant difference in BMI, mean albumin levels, operating time required, mortality and minor complications after surgery. One patient in the TCP group suddenly died on the day of discharge due to a cardiac event. When patient groups with or without complications were compared, factors such as presence of >1 comorbidity(p=0.019; odds ratio: 3.16) and periampullary type of tumours (PAC) (p=0.011; odds ratio: 7.91) reached statistical significance on multivariate analysis. Four patients in the TCP group developed grade A DGE and three of these had prolonged drain output while one developed grade A PF. No patient from this group suffered bile leak or PPH. We assessed amylase levels in the three patients who suffered prolonged drain output (Table 5) and found normal preoperative serum amylase levels (<120u/L) in all of them. All three patients had very low pancreatic juice amylase levels (<500u/L) and their drain amylase levels were three times lower than their serum values.

Subgroup analysis of patients with and without complications is shown in Table 3. Twenty-one patients were suffering from tropical chronic pancreatitis (TCP) which is well known to influence onset of PF by nature of its pathophysiology. So we further compared patients with (n=21) and without (n=55) TCP. This subgroup analysis showed increased incidence of DM, larger pancreatic duct size, lower pancreatic juice amylase levels and lower rates of major morbidity among TCP patients (Table 4). The two groups showed no significant difference in BMI, mean albumin levels, operating time required, mortality and minor complications after surgery. One patient in the TCP group suddenly died on the day of discharge due to a cardiac event. When patient groups with or without complications were compared, factors such as presence of >1 comorbidity(p=0.019; odds ratio: 3.16) and periampullary type of tumours (PAC) (p=0.011; odds ratio: 7.91) reached statistical significance on multivariate analysis. Four patients in the TCP group developed grade A DGE and three of these had prolonged drain output while one developed grade A PF. No patient from this group suffered bile leak or PPH. We assessed amylase levels in the three patients who suffered prolonged drain output (Table 5) and found normal preoperative serum amylase levels (<120u/L) in all of them. All three patients had very low pancreatic juice amylase levels (<500u/L) and their drain amylase levels were three times lower than their serum values.

Discussion

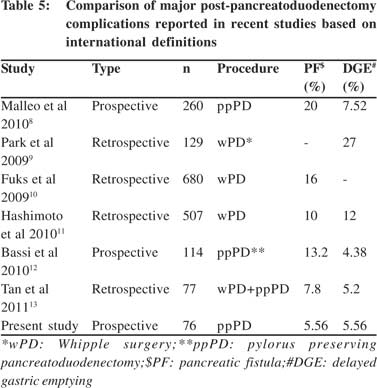

The lack of uniform definitions for postpancreatoduodenectomy complications have resulted in reports of highly variable incidence rates. The recent introduction of international study group definitions for the postoperative morbidity following PD has enabled us to compare postoperative complications with respect to different surgical techniques and pathological conditions for which they are employed. Most of the studies have analysed the validity of these definitions on retrospective case series. We carried out this comprehensive prospective study by precisely applying the guidelines recommended by these definitions. The median age of our patients was lower than that reported in literature, which may be due to the higher number of TCP patients in our cohort. Preoperative comorbidity was present in 87% patients who underwent ppPD with DM being the commonest (43.4%) given that majority of our patients suffered from TCP. The overall postoperative complications rate in our patients (29.17%) is similar to that reported by Vin et al (20- 60%), though significantly lower than Malleo et al.[7,8] The incidence of significant PF is very low (5.26%) in our series compared to other prospective and retrospective series of PD (Table 5).[8-13] These results are not influenced due to chronic pancreatitis patients, who have atrophic pancreas and low chance of developing PF, and the incidence remains low even after excluding them (7.3%). High volume PD, adoption of uniform technique of duct to mucosa anastomosis and performance of PJ by experienced consultants, are the proposed reasons of low incidence of PF in our series. When four patients with significant PF were analysed, all had associated comorbidities including PAC, prolonged hospital stay, significant DGE, two patients had other complications as well and one died. Thus the incidence of significant PF in our series directly correlates with the incidence of other major comorbidities and need for interventions, which correlates with the ISGPF grading proposed by Bassi et al.[4] This highlights the need for strategies to prevent postoperative PF following PD. Duct to mucosa vs. dunking method of PJ reconstruction has always been an area of active debate in terms of preventing PF. Since all our cases underwent duct to mucosa PJ, this study can not determine which technique is superior. Pylorus preservation in PD has been criticized by the increased incidence of DGE when compared to the classical Whipple operation.[14,15] Pylorus preservation with mechanical dilatation of sphincter has been suggested to decrease the incidence of DGE.[16,17] Studies on DGE with antecolic vs. retrocolic DJ reconstruction favour the former.[18,19] But to perform either of these, the stomach and duodenum have to be mobilised completely and straightened out to bring them either behind or in front of the colon (Figure 2).[2] The proposed advantages of antecolic anastamosis in terms of DGE are increased mobility of stomach, absence of mechanical obstruction and anatomical barrier between PJ and DJ. But we keep the right gastric pedicle and gastro-hepatic omentum intact so as to avoid denervation of first part of duodenum. DJ is constructed to the same loop of jejunum distal to PJ and HJ and the incidence (5.26%) of significant DGE is comparable to 5% incidence as reported by Tani et al and significantly lower compared to <15% reported by Neoptolemos et al with antecolic DJ.[2,20] Some authors report that pylorus preservation has no role in the incidence of DGE.[8,21] DGE that developed in our series were all associated with some postoperative comorbidity and can be termed as secondary DGE. There was no grade C or primary form of DGE (without any postoperative comorbidity) in our series. We speculate that this may be due to the intact vagal innervations to the pylorus and first part of duodenum as described by Yi et al, and highlights the need for preservation of neurovascular supply to the pyloro-duodenal region by careful dissection in this area.[22]

When patient groups with or without complications were compared, factors such as presence of >1 comorbidity and periampullary type of tumours (PAC) reached statistical significance. Though not statistically significant, patients with higher BMI had slightly higher risk for complications. High BMI as a risk factor for post-PD complications has been reported in previous studies as well.[23,24] Multivariate analysis of risk factors influencing development of complications revealed PAC (p=0.011; odds ratio: 7.91) and presence of comorbidity (p=0.019; odds ratio: 3.16) to be significant independent risks. Periampullary tumours are associated with an undilated pancreatic duct and soft pancreas, both conditions favouring development of a PF.[10,11] In the present study, median duct size was no different in both the groups emphasizing that careful construction of PJ is the key to preventing most PD related complications.

PD in chronic pancreatitis (CP) is performed for a pancreatic head mass (PHM), suspected malignancy, and obstructive jaundice. TCP is a well known premalignant condition leading to a higher incidence (30-80%) of pancreatic cancer than western type of CP.[3] The commonest comorbidity in our TCP patients was DGE and prolonged drainage. DGE may herald an otherwise undetected pancreatico-enteric or bilio-enteric anastamotic leak. A pancreatic anastamotic leak may clinically be overt as a PF or may manifest only as DGE.[25] From the observations of our patients with DGE, one patient had PF as per the ISGPF definition and three had prolonged drainage with low pancreatic fluid amylase levels. A fibrosed firm gland with dilated pancreatic ducts in chronic pancreatitis carries a lower chance of postoperative leak, but a subgroup of patients with TCP can have a fat replaced soft pancreas which too is soft and friable for suturing.[26-28] So we speculate that the prolonged drainage seen in our patients might be due to the development of pancreatic fistula, even though the drainage had low amylase levels. A TCP pancreas given its pathophysiology produces low levels of amylase. A pancreatic leak in these patients may not produce a rise in drain fluid amylase levels despite a leak being actually there. Hence, the current ISGPS definition of PF may not be valid when applied in the setting of TCP. Studies on pancreatic fistula have not incorporated pancreatic juice amylase levels for comparison yet.

In conclusion, pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy can be performed not only with reduced mortality, but very low morbidity as well. Comorbid conditions and periampullary tumours are associated with more postoperative complications. Delayed gastric emptying is not significantly increased with pylorus preservation and modified retrocolic duodenojejunostomy. Most DGE occurs as a sequelae to comorbidity (secondary DGE). Primary DGE may be prevented by careful preservation of the neurovascular supply to pylorus and first part of duodenum. The ISGPF grading of severe pancreatic fistula is well correlated in clinical situations. Low production of pancreatic amylase in chronic pancreatitis can fail to identify a fistula given the current ISGPS definition.

References

Discussion

The lack of uniform definitions for postpancreatoduodenectomy complications have resulted in reports of highly variable incidence rates. The recent introduction of international study group definitions for the postoperative morbidity following PD has enabled us to compare postoperative complications with respect to different surgical techniques and pathological conditions for which they are employed. Most of the studies have analysed the validity of these definitions on retrospective case series. We carried out this comprehensive prospective study by precisely applying the guidelines recommended by these definitions. The median age of our patients was lower than that reported in literature, which may be due to the higher number of TCP patients in our cohort. Preoperative comorbidity was present in 87% patients who underwent ppPD with DM being the commonest (43.4%) given that majority of our patients suffered from TCP. The overall postoperative complications rate in our patients (29.17%) is similar to that reported by Vin et al (20- 60%), though significantly lower than Malleo et al.[7,8] The incidence of significant PF is very low (5.26%) in our series compared to other prospective and retrospective series of PD (Table 5).[8-13] These results are not influenced due to chronic pancreatitis patients, who have atrophic pancreas and low chance of developing PF, and the incidence remains low even after excluding them (7.3%). High volume PD, adoption of uniform technique of duct to mucosa anastomosis and performance of PJ by experienced consultants, are the proposed reasons of low incidence of PF in our series. When four patients with significant PF were analysed, all had associated comorbidities including PAC, prolonged hospital stay, significant DGE, two patients had other complications as well and one died. Thus the incidence of significant PF in our series directly correlates with the incidence of other major comorbidities and need for interventions, which correlates with the ISGPF grading proposed by Bassi et al.[4] This highlights the need for strategies to prevent postoperative PF following PD. Duct to mucosa vs. dunking method of PJ reconstruction has always been an area of active debate in terms of preventing PF. Since all our cases underwent duct to mucosa PJ, this study can not determine which technique is superior. Pylorus preservation in PD has been criticized by the increased incidence of DGE when compared to the classical Whipple operation.[14,15] Pylorus preservation with mechanical dilatation of sphincter has been suggested to decrease the incidence of DGE.[16,17] Studies on DGE with antecolic vs. retrocolic DJ reconstruction favour the former.[18,19] But to perform either of these, the stomach and duodenum have to be mobilised completely and straightened out to bring them either behind or in front of the colon (Figure 2).[2] The proposed advantages of antecolic anastamosis in terms of DGE are increased mobility of stomach, absence of mechanical obstruction and anatomical barrier between PJ and DJ. But we keep the right gastric pedicle and gastro-hepatic omentum intact so as to avoid denervation of first part of duodenum. DJ is constructed to the same loop of jejunum distal to PJ and HJ and the incidence (5.26%) of significant DGE is comparable to 5% incidence as reported by Tani et al and significantly lower compared to <15% reported by Neoptolemos et al with antecolic DJ.[2,20] Some authors report that pylorus preservation has no role in the incidence of DGE.[8,21] DGE that developed in our series were all associated with some postoperative comorbidity and can be termed as secondary DGE. There was no grade C or primary form of DGE (without any postoperative comorbidity) in our series. We speculate that this may be due to the intact vagal innervations to the pylorus and first part of duodenum as described by Yi et al, and highlights the need for preservation of neurovascular supply to the pyloro-duodenal region by careful dissection in this area.[22]

When patient groups with or without complications were compared, factors such as presence of >1 comorbidity and periampullary type of tumours (PAC) reached statistical significance. Though not statistically significant, patients with higher BMI had slightly higher risk for complications. High BMI as a risk factor for post-PD complications has been reported in previous studies as well.[23,24] Multivariate analysis of risk factors influencing development of complications revealed PAC (p=0.011; odds ratio: 7.91) and presence of comorbidity (p=0.019; odds ratio: 3.16) to be significant independent risks. Periampullary tumours are associated with an undilated pancreatic duct and soft pancreas, both conditions favouring development of a PF.[10,11] In the present study, median duct size was no different in both the groups emphasizing that careful construction of PJ is the key to preventing most PD related complications.

PD in chronic pancreatitis (CP) is performed for a pancreatic head mass (PHM), suspected malignancy, and obstructive jaundice. TCP is a well known premalignant condition leading to a higher incidence (30-80%) of pancreatic cancer than western type of CP.[3] The commonest comorbidity in our TCP patients was DGE and prolonged drainage. DGE may herald an otherwise undetected pancreatico-enteric or bilio-enteric anastamotic leak. A pancreatic anastamotic leak may clinically be overt as a PF or may manifest only as DGE.[25] From the observations of our patients with DGE, one patient had PF as per the ISGPF definition and three had prolonged drainage with low pancreatic fluid amylase levels. A fibrosed firm gland with dilated pancreatic ducts in chronic pancreatitis carries a lower chance of postoperative leak, but a subgroup of patients with TCP can have a fat replaced soft pancreas which too is soft and friable for suturing.[26-28] So we speculate that the prolonged drainage seen in our patients might be due to the development of pancreatic fistula, even though the drainage had low amylase levels. A TCP pancreas given its pathophysiology produces low levels of amylase. A pancreatic leak in these patients may not produce a rise in drain fluid amylase levels despite a leak being actually there. Hence, the current ISGPS definition of PF may not be valid when applied in the setting of TCP. Studies on pancreatic fistula have not incorporated pancreatic juice amylase levels for comparison yet.

In conclusion, pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy can be performed not only with reduced mortality, but very low morbidity as well. Comorbid conditions and periampullary tumours are associated with more postoperative complications. Delayed gastric emptying is not significantly increased with pylorus preservation and modified retrocolic duodenojejunostomy. Most DGE occurs as a sequelae to comorbidity (secondary DGE). Primary DGE may be prevented by careful preservation of the neurovascular supply to pylorus and first part of duodenum. The ISGPF grading of severe pancreatic fistula is well correlated in clinical situations. Low production of pancreatic amylase in chronic pancreatitis can fail to identify a fistula given the current ISGPS definition.

References

- Bassi C, Salvia R, Butturini G, Marcucci S, Barugola G, Falconi M. Value of regional lymphadenectomy in pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford). 2005;7:87–92.

- Tani M, Terasawa H, Kawai M, Ina S, Hirono S, Uchiyama K, et al. Improvement of delayed gastric emptying in pyloruspreserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243:316–20.

- Beger HG, Rau BM, Poch B. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection. In: Beger HG, Matsuno S, Cameron JL, editors. Diseases of the pancreas. Current surgical therapy. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2008. p. 399–412.

- Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13.

- Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761–8.

- Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20–5.

- Vin Y, Sima CS, Getrajdman GI, Brown KT, Covey A, Brennan MF, et al. Management and outcomes of postpancreatectomy fistula, leak, and abscess: results of 908 patients resected at a single institution between 2000 and 2005. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:490–8.

- Malleo G, Crippa S, Butturini G, Salvia R, Partelli S, Rossini R, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: validation of International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery classification and analysis of risk factors. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:610–8.

- Park JS, Hwang HK, Kim JK, Cho SI, Yoon DS, Lee WJ, et al. Clinical validation and risk factors for delayed gastric emptying based on the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Classification. Surgery. 2009;146:882–7.

- Fuks D, Piessen G, Huet E, Tavernier M, Zerbib P, Michot F, et al. Life-threatening postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade C) after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. Am J Surg. 2009;197:702–9.

- Hashimoto Y, Traverso LW. Incidence of pancreatic anastomotic failure and delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy in 507 consecutive patients: use of a web-based calculator to improve homogeneity of definition. Surgery. 2010;147:503–15.

- Bassi C, Molinari E, Malleo G, Crippa S, Butturini G, Salvia R, et al. Early versus late drain removal after standard pancreatic resections: results of a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:207–14.

- Tan WJ, Kow AW, Liau KH. Moving towards the New International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definitions in pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comparison between the old and new. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:566–72.

- van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Gulik TM, DeWit LT, Allema JH, Rauws EA, Obertop H, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy versus pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of 200 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:373–9.

- Balcom JHt, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391–8.

- Bassi C, Falconi M, Salvia R, Mascetta G, Molinari E, Pederzoli P. Management of complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high volume centre: results on 150 consecutive patients. Dig Surg. 2001;18:453–7; discussion 8.

- Fischer CP, Hong JC. Method of pyloric reconstruction and impact upon delayed gastric emptying and hospital stay after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:215–9.

- Yeo CJ, Barry MK, Sauter PK, Sostre S, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, et al. Erythromycin accelerates gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. A prospective, randomized, placebocontrolled trial. Ann Surg. 1993;218:229–37; discussion 37–8.

- Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:603–7.

- Neoptolemos JP, Russell RC, Bramhall S, Theis B. Low mortality following resection for pancreatic and periampullary tumours in 1026 patients: UK survey of specialist pancreatic units. UK Pancreatic Cancer Group. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1370–6.

- Horstmann O, Markus PM, Ghadimi MB, Becker H. Pylorus preservation has no impact on delayed gastric emptying after pancreatic head resection. Pancreas. 2004;28:69–74.

- Yi SQ, Ru F, Ohta T, Terayama H, Naito M, Hayashi S, et al. Surgical anatomy of the innervation of pylorus in human and Suncus murinus, in relation to surgica technique for pyloruspreserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2209–16.

- Ito Y, Kenmochi T, Irino T, Egawa T, Hayashi S, Nagashima A, et al. The impact of obesity on perioperative outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2618–22.

- House MG, Fong Y, Arnaoutakis DJ, Sharma R, Winston CB, Protic M, et al. Preoperative predictors for complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: impact of BMI and body fat distribution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:270–8.

- Schafer M, Mullhaupt B, Clavien PA. Evidence-based pancreatic head resection for pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2002;236:137–48.

- Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:951–9.

- van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Wit LT, Van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: drainage versus resection of the pancreatic remnant. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:18–24.

- Ramesh H. Tropical chronic pancreatitis. In: Beger HG, Matsuno S, Cameron JL, editors. Diseases of the pancreas. Current surgical therapy. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2008. p. 349–59.

|

|

|

|

|

|