|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

colorectal cancer, screening, fecal occult blood, colonoscopy |

|

|

Anil John,1,2 Saad Al Kaabi,1 Nazeeh Dweik,1 Rafie Yakoub,1 Anjum John,3 Muneera Al Mohannadi,1 Manik Sharma,1 Hamid Wani,1 MT Butt,1 MF Derbala,1 Kakil Rasul,4 Durraiya Al Qahtani,5 Mona Taher,5 Hayam Al Sada,5 Jamal Suleiman,5 Issa Ghanem,5 Farida Abdulla5

Department of Gastroenterology,1

Hamad General Hospital,

Weill Cornell Medical College,2

Medical Research Center, Hamad

Medical Corporation,3

Department of Oncology, NCCCR,4

Family Medicine, Primary Health

Care Corporation,5

Doha, Qatar

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Anil John

Email: aniljohn44@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.159

Abstract

Background and aim: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading causes of cancer related mortality globally. Though Asia has traditionally been considered a relatively low incidence area for colorectal cancer, the incidence is reportedly increasing. The Asia Pacific Working Group for Colorectal Cancer has recommended screening of individuals at average risk starting from 50 years of age. Based on these recommendations we conducted a pilot study to assess the need and feasibility of a colorectal cancer screening program in the state of Qatar. Methods and results: We screened 1385 individuals by fecal immunochemical testing for occult blood, at the primary health center level and positive cases were referred for colonoscopy. Among those who tested positive for fecal occult blood, we picked up five patients with cancers and seven with neolastic polyps.

Conclusion: Our results compare with the yield of screening programs in western countries thus suggesting an emerging role for colorectal cancer screening in Asian countries.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|662 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Colorectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality globally.[1]The high incidence and associated mortality of colorectal cancer in the western population has prompted initiation of effective screening programs supported by screening guidelines.[2] The current decline in colorectal cancer related mortality has been attributed to effective screening programs which are in place in the West.[3]Although Asia has traditionally been considered a region of relatively low colorectal cancer burden, current reports indicate an increasing incidence.[4]Given the increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia, the Asia Pacific Working Group for Colorectal Cancer has been deliberating the need for screening programs.[5]The group published their consensus recommendations advocating initiation of colorectal cancer screening in individuals at average risk, starting from the age of 50 years.[6]In the light of above recommendations, we initiated a pilot study to assess the need and feasibility of a national colorectal cancer screening program in the State of Qatar.

Methods

The screening program was initiated as a pilot study at three primary health centers which were selected randomly. Healthy asymptomatic individuals aged 40 to 74 years, with only average risk for colorectal cancer was the target population for screening. Exclusions included those with personal history of colorectal cancer or polyps, those with family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps in at least one first degree relative before the age of 60 years, and those with family history of colorectal cancer in two first degree relatives diagnosed at any age. In addition, anyone who reported new onset gastrointestinal symptoms, recent weight loss, change in bowel habits or bleeding per rectum was excluded from screening and directly referred for evaluation in the gastroenterology clinic. Any of the individuals who have had normal total colonoscopy within the last five years, was also excluded. Individuals with significant co-morbidities, with poor life expectancy, in whom screening was considered irrelevant, were also excluded.

All healthy individuals who were eligible for screening were invited to undergo fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) using rapid fecal occult blood test by a sensitive immunochromatographic sandwich card assay for human hemoglobin in the feces(Boson Biotech Co. Ltd.,www.bosonbio.com). In the event if a test was read positive by the primary health nurse, the individual was fast tracked for a total colonoscopy at the participating tertiary care hospital. Total colonoscopy was performed by an experienced endoscopist under conscious sedation. All subjects screened positive were directed to undergo optimal bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol solution prior to colonoscopy. It was mandatory to have photographic documentation of the cecum during colonoscopy and a minimum withdrawal time of seven minutes was adhered to. Those found to have polyps underwent endoscopic polypectomy and any suspicious lesions detected were biopsied. A database was maintained at the primary health center for all patients enrolled in the screening program and another database was maintained at the endoscopy unit for all referrals received, colonoscopic procedures done and for the histopathology reports.

Results

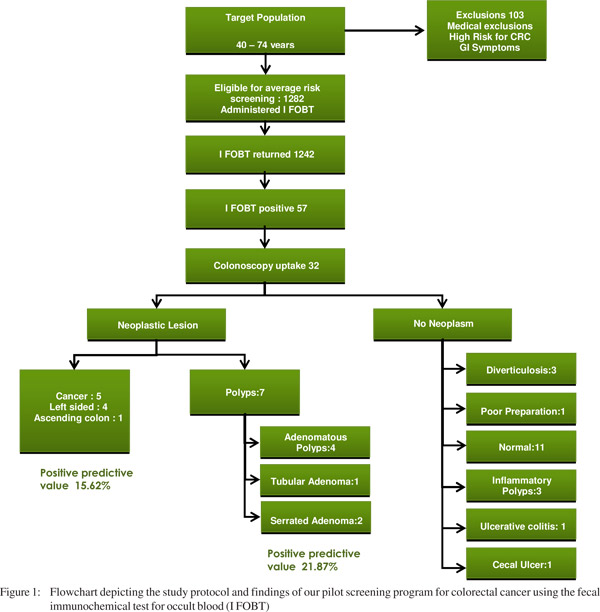

A total of 1358 individuals reported for screening. However those with gastrointestinal symptoms and those considered to be at high risk for colorectal cancer were directly referred for evaluation to the Gastroenterology clinic at the participating institution, thus excluding them from the average risk screening protocol.Individuals with significant comorbidities, in whom screening was considered irrelevant, were also excluded. A total of 103 individuals were excluded. Forty individuals failed to return the fecal immunochemical (FIT) kit. Thus after successfully enrolling 1242 healthy individuals (comprising 393 females) for average risk screening by fecal immunochemical test (FIT) at the primary health care centers, we performed an interim analysis to ascertain the utility of the screening program. Fecal occult blood was positive in 57individuals (4.5%). Of the 57 who were eligible for colonoscopy only 32 (56.14 %) agreed and reported for the procedure at the endoscopy unit. Of the 32 colonoscopies, 20 did not show any evidence of neoplasia, while 12 were found harboring neoplastic lesions. Of the 12 patients with neoplastic lesions, five had cancer and seven had polyps. Of the five cancers picked up during our screening program, three had recto-sigmoid lesions, one had lesion in the descending colon and one in the ascending colon. All carcinomatous lesions except one were amenable for surgical resection. Of the seven polyps, four were adenomatous polyps, one was tubular adenomas and two were serrated adenomas (Figure 1).

Discussion

This was a pilot study conducted at the primary health center level to assess the need and feasibility of a national program for colorectal cancer screening in Qatar.The screening program targeted healthy asymptomatic individuals between the ages of 40 and 74 with only average risk for colorectal cancer.After screening 1242 individuals by fecal immunochemical testing, our interim analysis revealed five cancerous lesions and seven neoplastic polyps. The positivity rate of the fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) in the screened population was 4.5% (57/1248). Most colorectal community screening studies employing the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) yield a 3-4% positivity rate.[7]

Our colonoscopy uptake rate (~60%) was sub-optimal, since an efficient screening program achieves a colonoscopy uptake rate exceeding 80%.[8] We achieved 100% cecal intubation rates during colonoscopy. A colorectal cancer screening program usually attains an 80-90% rate of total colonoscopy and complete examination of the colon; and we bettered this target.[9] The positive predictive value for cancer was 15.6% and for polyps was 28.12%.Similar rates have been reported in screening programs elsewhere, employing fecal blood assays.[10] A positive fecal occult blood testing screens out individuals who are likely to have neoplastic lesions on colonoscopy.The positive predictive value of fecal occult blood test is much lower (5-8%) for an average risk individual undergoing colonoscopy.[11]

The goal of a mass screening program is to detect cancers at an early stage permitting curative treatment at lower costs with better outcomes, using a safe screening method.[12] We had a very low rate of adverse events associated with colonoscopy under conscious sedation. Only two patients had mild post-polypectomy bleeding which was controlled by endoscopic measures. The rates of bleeding and perforation in large colorectal cancer screening studies have been less than 1%.[13] The results of our pilot study are comparable to the screening results in countries like France, which have a high incidence of colorectal cancer is their community.[14]Given that our screening program was picking up a significant number of individuals with silent colorectal cancer, we decided to terminate our pilot study and recommend a larger feasibility study for bowel cancer screening to the Supreme Council of Health (SCH, Qatar). The SCH is the apex policy making body on health affairs for the government of the State of Qatar. We have thus recommended a vertical population based screening program at the primary health center level. Qatar is a geographically small country with a population of 2 million.Its health care infrastructure consists of 24 health centers linked to large tertiary care hospitals. This model of health care delivery is ideally suited for a colorectal cancer screening program with all its inherent advantages and benefits, over opportunistic screening.[15]We recommend the use of annual fecal immunochemical testing for colorectal cancer screening at the primary health center level. This recommendation is based on evidence of high sensitivity, high positive predictive value, good adherence and cost effectiveness for detecting silent colorectal cancer and reduction in mortality.[16] Most international guidelines for colorectal cancer screening programs[2,17] recommend that screening should be commenced at 50 years of age for individuals at average risk. However in our pilot study we chose 40 years as the cut off for initiating screening and we based this criteria on published literature from Qatar where around 20% of colorectal cancers are diagnosed before the age of 50 years.[18]Although the number of individuals screened in this study were relatively low and the overall colonoscopy uptake was below par, we have gained valuable insights from the data generated. Importantly this pilot study highlights, contrary to common belief in Asia, that there is a significant burden of asymptomatic colorectal cancer and polyps present in our community and regular screening programs are essential to address this challenge. In conclusion, there is an emerging role and justification for ongoing screening programs for colorectal cancer in the State of Qatar and other Asian countries. Our data indicates the need for systematic feasibility studies for organizing nation wide screening programs in Asian countries.

References

The goal of a mass screening program is to detect cancers at an early stage permitting curative treatment at lower costs with better outcomes, using a safe screening method.[12] We had a very low rate of adverse events associated with colonoscopy under conscious sedation. Only two patients had mild post-polypectomy bleeding which was controlled by endoscopic measures. The rates of bleeding and perforation in large colorectal cancer screening studies have been less than 1%.[13] The results of our pilot study are comparable to the screening results in countries like France, which have a high incidence of colorectal cancer is their community.[14]Given that our screening program was picking up a significant number of individuals with silent colorectal cancer, we decided to terminate our pilot study and recommend a larger feasibility study for bowel cancer screening to the Supreme Council of Health (SCH, Qatar). The SCH is the apex policy making body on health affairs for the government of the State of Qatar. We have thus recommended a vertical population based screening program at the primary health center level. Qatar is a geographically small country with a population of 2 million.Its health care infrastructure consists of 24 health centers linked to large tertiary care hospitals. This model of health care delivery is ideally suited for a colorectal cancer screening program with all its inherent advantages and benefits, over opportunistic screening.[15]We recommend the use of annual fecal immunochemical testing for colorectal cancer screening at the primary health center level. This recommendation is based on evidence of high sensitivity, high positive predictive value, good adherence and cost effectiveness for detecting silent colorectal cancer and reduction in mortality.[16] Most international guidelines for colorectal cancer screening programs[2,17] recommend that screening should be commenced at 50 years of age for individuals at average risk. However in our pilot study we chose 40 years as the cut off for initiating screening and we based this criteria on published literature from Qatar where around 20% of colorectal cancers are diagnosed before the age of 50 years.[18]Although the number of individuals screened in this study were relatively low and the overall colonoscopy uptake was below par, we have gained valuable insights from the data generated. Importantly this pilot study highlights, contrary to common belief in Asia, that there is a significant burden of asymptomatic colorectal cancer and polyps present in our community and regular screening programs are essential to address this challenge. In conclusion, there is an emerging role and justification for ongoing screening programs for colorectal cancer in the State of Qatar and other Asian countries. Our data indicates the need for systematic feasibility studies for organizing nation wide screening programs in Asian countries.

References

- Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–43.

- Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50.

- Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA,Eheman C, Zauber AG, Anderson RN, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–73.

- Boyle P, Levin B, editors. World Cancer Report 2008. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008.

- Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK, Asia Pacific Working Group on Colorectal C. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:871–6.

- Sung JJ, Lau JY, Young GP, Sano Y, Chiu HM, Byeon JS, et al. Asia Pacific consensus recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2008;57:1166–76.

- Jorgensen OD, Kronborg O, Fenger C. A randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer using faecal occult blood testing: results after 13 years and seven biennial screening rounds. Gut. 2002;50:29–32.

- Goulard H, Boussac-Zarebska M, Ancelle-Park R, Bloch J. French colorectal cancer screening pilot programme: results of the first round. J Med Screen. 2008;15:143–8.

- Faivre J, Dancourt V, Lejeune C, Tazi MA, Lamour J, Gerard D, et al. Reduction in colorectal cancer mortality by fecal occult blood screening in a French controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1674–80.

- Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1541–9.

- Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:162–8.

- Chiu HM, Wang HP, Lee YC, Huang SP, Lai YP, Shun CT, et al. A prospective study of the frequency and the topographical distribution of colon neoplasia in asymptomatic average-risk Chinese adults as determined by colonoscopic screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:547–53.

- Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Results of screening colonoscopy among persons 40 to 49 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1781–5.

- Manfredi S, Piette C, Durand G, Plihon G, Mallard G, Bretagne JF. Colonoscopy results of a French regional FOBT-based colorectal cancer screening program with high compliance. Endoscopy. 2008;40:422–7.

- Madlensky L, Goel V, Polzer J, Ashbury FD. Assessing the evidence for organised cancer screening programmes. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1648–53.

- Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–71.

- Force USPST. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627–37.

- Rasul KI, Awidi AS, Mubarak AA, Al-Homsi UM. Study of colorectal cancer in Qatar. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:705–7.

|

|

|

|

|

|