48uep6bbphidvals|659

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

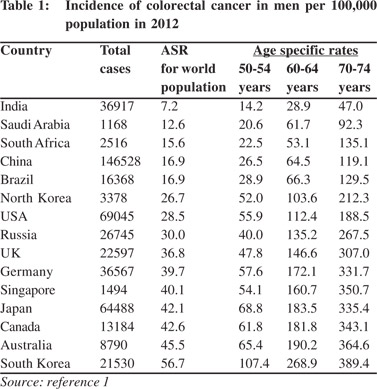

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading cause of mortality and morbidity from cancer.[1] Several developed Asians countries have surpassed the United States and other Western European countries in burden of CRC (Table 1). Although the incidence of CRC in India has increased only marginally, it is now the fifth most common cause of cancer mortality among Indian men and women.[1,2] The incidence of CRC is still several folds lower in India than in most developing and developed countries and there is no scientific evidence for starting a CRC screening program in India. The incidence of CRC across all ages is low, as is the prevalence of adenomas, which is even lower. Furthermore, there is a substantial shortfall in availability of safe and high quality endoscopy facilities. Occult blood testing in stool is fraught with numerous false positives in Indians and Asians.[3] Cancer screening has been in the eye of a stormy debate in recent years. Screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer, the commonest cancers in women and men in Western countries have been highly controversial. One article speculates ceasing government sponsored breast cancer screening in Switzerland.[4] They contend that from an ethical perspective, a public health program that does not clearly produce more benefits than harms is hard to justify. Providing clear, unbiased information, promoting appropriate care, and preventing over-diagnosis and overtreatment would be a better choice.[4]

The benefit of population screening in reducing the mortality from CRC is now well proven.[5] Recent results from a long follow-up of CRC screening trials and population based incidence data indicate that screening has reduced the incidence and mortality from CRC in many Western countries.[5-8] At the same time the incidence and mortality rates from CRC continue to be high or increasing in countries where screening is not offered to the populations.[1] The National Polyp Study, which followed up 2,602 patients who had adenomas removed by colonoscopic polypectomy showed a 53% reduction in mortality over long term followup.[6] A population based case control study from Germany reported screening colonoscopy to have the highest impact on reducing the risk of invasive CRC.[7] Recent population based cancer registry data from the USA has revealed that screening has helped to reduce the CRC burden by 30%.[8]

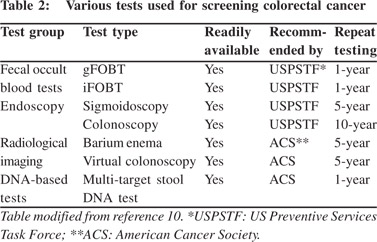

The success of CRC screening can be attributed to some unique features that make CRC highly suited for preventive screening. First, most CRC arise as small adenomas and then progress over many years to become an advanced adenoma, and eventually progress to carcinoma-in-situ and frank carcinoma.[9] The colorectal carcinogenesis from small adenoma to invasive carcinoma is a long process lasting decades and offers sufficient time for preventive interventions. Secondly, as pre-malignant adenomas develop and progress, mucosal ulcerations occur, shedding blood and tumor cells into the lumen and ultimately are passed out in feces. This allows the use of several home-based fecal blood tests for CRC (Table 2).[10] Third and most importantly, a colonoscopy performed for primary screening or following a positive screening test (less invasive/ home-based test) will allow direct visualization of the pre-malignant lesions such as small and large adenomas and allow their complete removal simultaneously by polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection.[11] The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines classify CRC screening tests into cancer prevention tests and cancer detection tests.[12] Colonoscopy directly prevents CRC by detecting and removing precursor lesions.

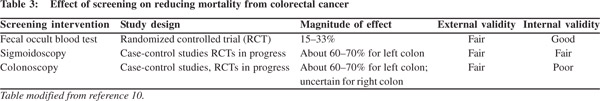

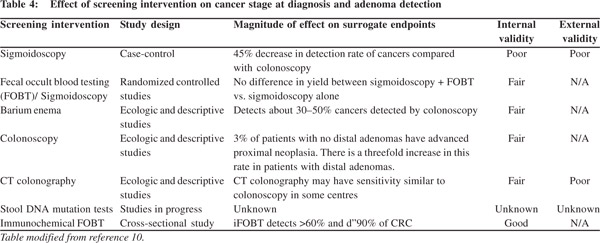

The major drawbacks associated with CRC screening programs include: poor compliance to colonoscopy, missed adenomas due to poor bowel preparation or inappropriate colonoscopy techniques, prohibitive cost of setting up a program to carry out repeat colonoscopies in high-risk individuals and the cost of managing complications.[5,10,12] As a result a lot effort has been directed to develop practical, user friendly tests which are easy to perform and have high sensitivity (Table 3). Fecal occult blood tests have evolved from benzidine-based, guaiac-based and immunology-based tests.[10,12] New methods for screening colorectal cancer, such as virtual colonoscopy and multiple target DNA testing in stool samples are now available and approved for use.[10-14] Liquid biopsy of circulating CRC cells and cell free DNA from plasma are experimental modalities likely to become clinical reality in the near future.[15] All these tests ultimately help to screen and triage high-risk patients who can be further motivated to undergo colonoscopy (Table 4). The ultimate success of any CRC screening program is heavily dependent on the participation and compliance of the people being screened,[16] as well as the quality of the colonoscopy and polypectomy in the community.[17]

Colonoscopy allows for direct visualization of polyps and small tumours and their simultaneous removal during a single procedure. Therefore colonoscopy is the preferred screening method for CRC prevention.[12] Notwithstanding its advantages colonoscopy has borne the brunt of many jokes, cartoons, limericks and media outbursts and a general Google search for the keywords “colonoscopy experience” throws up two million hits. An uncomfortable experience during bowel preparation or difficult colonoscopy or an incomplete polypectomy is enough to deter the patient and his/her contacts to avoid colonoscopy screening. It is very important to have good bowel preparation to allow high quality colonoscopy and proper documentation of findings.[18,19] Others argue that the best test is the one that actually gets taken. In the era of personalized medicine, patient needs and preferences vary a lot and influence their acceptance and compliance. Despite the availability of a range of CRC screening tests, a large proportion of the population in general and South Asians in particular do not undergo regular screening.[16,20]

Successful triage based on domiciliary testing has great potential. In the future better non-invasive testing using stool DNA might make colorectal cancer screening more acceptable. In a recently published trial, Imperiale et al evaluated 9,989 asymptomatic, average-risk persons aged 50 to 84 years who were to undergo a screening colonoscopy, with a stool DNA test.[14] They collected stool specimens from the participants before standard bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Colonoscopy detected CRC in 65 (0.7%) subjects, of which 60 had stage I to III CRC. Colonoscopy also detected advanced precancerous lesions in 757 (7.6%) participants. The stool DNA test detected 60 of the 65 CRC (overall sensitivity 92.3%) and 321 of the 757 advanced precancerous lesions, including 27 of the 39 (69.2%) participants with high-grade dysplasia, and 42 of the 99 (42.4%) participants with sessile serrated polyps larger than one centimetre. The sensitivity of stool DNA positivity increased as lesion size increased, and was higher for distal, advanced, precancerous lesions than for proximal lesions (54.5% vs. 33.2%). The US FDA has licensed this new screening method. This study had combined multi-target DNA testing alongside colonoscopy. Whether such an approach will reduce mortality needs to be ascertained.

In summary, screening has reduced the incidence and mortality associated with colorectal cancer in the high incidence populations. Several CRC screening tests are now available and are broadly classified as cancer prevention tests and cancer detection tests. Not all of these tests have been proved beyond doubt to reduce mortality from CRC and are therefore not yet approved by various authorities and insurance companies. Colonoscopy every 10 years, beginning at age 50, is the recommended cancer prevention strategy in most western countries. Alternate screening options includes flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5–10 years, or a computed tomography based colonography every 5 years, or faecal immunochemical test for blood, as per individual preferences, availability and affordability of colonoscopy. Routine screening for CRC can’t be recommended in India due to several reasons including very low incidence rates of adenomas and CRC.

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [cited 2014 May 2]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr.

- Mallath MK, Taylor DG, Badwe RA, Rath GK, Shanta V, Pramesh CS, et al. The growing burden of cancer in India: epidemiology and social context. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e205–e12.

- Day LW, Cello JP, Somsouk M, Inadomi JM. Prevalence of gastric cancer versus colorectal cancer in Asians with a positive fecal occult blood test. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:209–16.

- Biller-Andorno N, Juni P. Abolishing mammography screening programs? A view from the Swiss Medical Board. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1965–7.

- Weinberg DS, Schoen RE. Screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-160-9- 201405060-01005.

- Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96.

- Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Jansen L, Knebel P, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer up to 10 years after screening, surveillance, or diagnostic colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:709–17.

- Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–17.

- Hill MJ, Morson BC, Bussey HJ. Aetiology of adenoma—carcinoma sequence in large bowel. Lancet. 1978;1:245–7.

- National Cancer Institute: PDQ® Colorectal Cancer Screening. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. [updated 2014 April 4; cited 2014 May 2]. Available from: http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/colorectal/HealthProfessional.

- Morson BC, Whiteway JE, Jones EA, Macrae FA, Williams CB. Histopathology and prognosis of malignant colorectal polyps treated by endoscopic polypectomy. Gut. 1984;25:437–44.

- Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50.

- Zalis ME, Blake MA, Cai W, Hahn PF, Halpern EF, Kazam IG, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of laxative-free computed tomographic colonography for detection of adenomatous polyps in asymptomatic adults: a prospective evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:692–702.

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Levin TR, Lavin P, Lidgard GP, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectalcancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1287–97.

- Perrone F, Lampis A, Bertan C, Verderio P, Ciniselli CM, Pizzamiglio S, et al. Circulating free DNA in a screening program for early colorectal cancer detection. Tumori. 2014;100:115–21.

- Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: Cultural influences or access to care? Cancer. 2006;107:184–92.

- Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298–306.

- Hernandez LV, Deas TM, Catalano MF, Guda NM, Huang L, Ketover SR, et al. Longitudinal assessment of colonoscopy quality indicators: a report from the Gastroenterology Practice Management Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014. pii: S0016-5107(14)01294–2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.1043.

- European Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines Working G, von Karsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N, Atkin W, Halloran S, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: overview and introduction to the full supplement publication. Endoscopy. 2013;45:51–9.

- Austin KL, Power E, Solarin I, Atkin WS, Wardle J, Robb KA. Perceived barriers to flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer among UK ethnic minority groups: a qualitative study. J Med Screen. 2009;16:174–9.