|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

severe autoimmune hepatitis, steroid therapy, liver transplantation |

|

|

Jeyamani Ramachandran,1 Sajith KG,1 Sandip Pal,1Jiffy Rasak VA,1 John Antony Jude Prakash,2 Banumathi Ramakrishna3

Departments of Hepatology,1

Microbiology2 and Pathology,3

Christian Medical College,

Vellore - 632004, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Jeyamani Ramachandran

Email: jeyapati@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.160

Abstract

Background: Severe autoimmune hepatitis is an entity which has been rarely reported in the Indian literature. We describe here the clinicopathological profile and treatment of severe autoimmune hepatitis (SAH) which is to the best of our knowledge the first report from India addressing this illness.

Methods and results: Between September 2010 and March 2013, 13 patients seeking treatment at our centre were diagnosed as SAH and treated with steroids. Jaundice along with coagulopathy was the presenting symptom in all these patients.Ascites was present in ten and encephalopathy in 6 patients. The median serum IgG was 2135mg/dl (range: 1122-5490).Significant titersof autoantibodies were present in all patients except one. Transjugular liver biopsy in 9 patients showed characteristic features of SAH such as extensive bridging necrosis and moderate to dense portal inflammation. With corticosteroid therapy, 10 patients survived while three died. In those who survived, biochemical improvement was seen as early as seven days with excellent long term remission.Conclusions: Clinical suspicion supported by liver biopsy and autoimmune serology led to the diagnosis of SAH in a cohort of patients with unexplained liver failure.Corticosteroids were beneficial in majority of patients affording excellent results and this could be predicted by early reduction in serum bilirubin within 7-15 days.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|663 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver, which when severe, can present with acute liver failure (ALF) or acute exacerbation of an unrecognized chronic liver disease, known as acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF).[1–4]This type of presentation is known as severe autoimmune hepatitis(SAH).[5]The diagnosis of SAH ischallenging in India because viral hepatitis is the commonest cause of ALF and ACLF here.[6,7]This entity has not been clearly defined in theAmerican Association of Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) or the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) guidelines,[8] but it is essential that hepatologists are aware of this uncommon presentation since corticosteroid therapy can be lifesaving for these patients.[3]This is particularly important in our country where resources for liver transplantation are limited. However, prolonged futile steroid therapy may also lead to sepsis and sabotage chances of subsequent liver transplantation. Hepatologists have to exercise a great degree of caution and judgement while initiating corticosteroids when appropriate and ceasing such therapy when harmful.[9] In this report we review our experience with SAH and describe the clinical, biochemical and serological profile of SAH patients. In addition we examined the efficacy, safety and predictors of response to steroid therapy in these patients.

Methods

We studied a cohort of 13 patients from September 2010 to January 2013 diagnosed withSAH and treated with corticosteroids. The diagnosis of SAH was made when a patient with probable autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) presented with acute onset jaundice with features of liver failure such as coagulopathywith or without encephalopathy. The diagnosis of AIH was confirmed after carefully ruling out other causes such as viral hepatitis A, B,C and E (negative serology for IgM anti-HAV, anti-HBc, anti-HCV, and anti-HEV), Wilson’s disease (serum ceruloplasmin and slit-lamp examination) and druginduced hepatitis including alcohol (detailed history), as the cause for unexplained liver failure. In the absence of above causes, a patient with either positive autoimmune serology (significant autoantibodies and elevated IgG) or characteristic liver biopsy(large areas of parenchymal necrosis with dense inflammatory infiltrate),[2,4,10,11] or both was diagnosed with SAH. Patients previously diagnosed with AIH who presented with relapse after drug withdrawal were not included in the study.

Transjugular liver biopsy was performed whenever possible. IgG antibodies to nuclear antigens (ANA), mitochondria (AMA), liver kidney microsomes (LKM)and smooth muscles (ASMA) were detected by the Liver Mosaic 8 immunofluorescence assay(IFA)(Euroimmun, Lubeck, Germany) and byenzyme-linked immunosorbent assays(ELISA) for soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas antigen (anti- SLA/LP, IgG ELISA, Euroimmun, Lubeck, Germany). All assays were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The patient sera were tested at dilutions of 1:40 and 1:80 for IFA and 1:100 for ELISA. The anti-SLA/LP ELISA was considered positive if the antibody concentration was e”20 units/ml.

Results

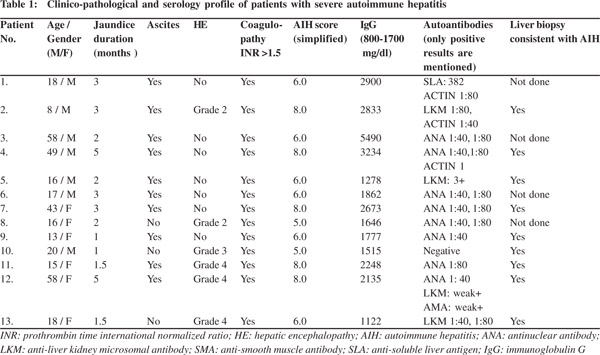

The study included 13 patients (seven males and six females) diagnosed with SAH and treated with corticosteroids.Fiftyseven people were diagnosed with AIH without an acute presentation during the same period and sixpatients presented with overlap syndrome.Thus SAH comprised 17% of the total 76 patients diagnosed with AIH during the study period.The age of SAH patients ranged from 8 to58 years (median: 17 years).The majority (9/13) of patients were less than 20 years of age. Jaundice was the presenting symptom in all patients, with a median duration of two months (range: 1–5 months). Ascites was the next most common presentation seen in ten patients.Two patients had hepatic encephalopathy (HE) at admission and four more developed during hospitalization. All 13 patients had coagulopathy (INR>1.5).There were no previous episodes of liver failure or liver disease in any of these patients. The blood parametersat admission were as follows: median serum bilirubin14.9 mg/dl (range: 3.8–31.0 mg/dl); median serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST)183IU/L (range: 115–750 IU/L); median serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT)117IU/L (range: 31-511 IU/L); median prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR)2.3(range: 1.6–3.5). Ultrasonography revealed features of chronic liver disease such as shrunken,coarse nodular liver in 11 patients;and hepatomegaly and heterogeneous echoes in the remaining two. Baseline clinical and laboratory parameters are provided in Table 1.

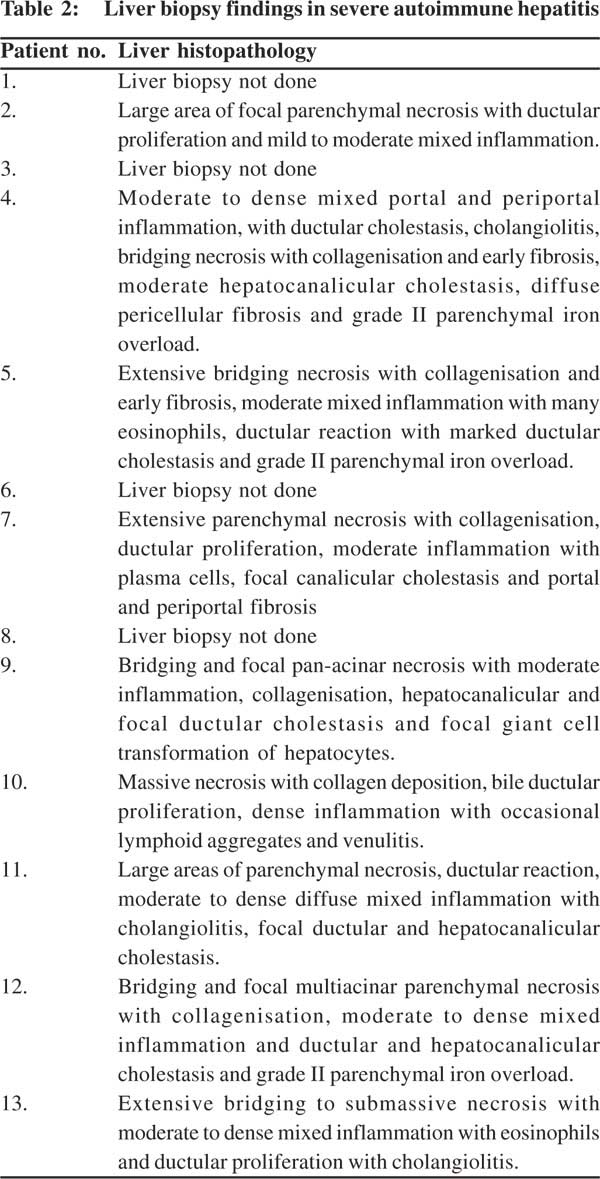

Histopathology findings

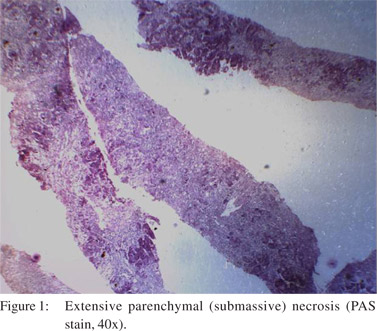

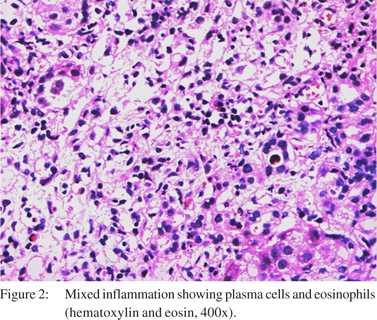

In view of coagulopathy, liver biopsy could be performed in nine cases and was performed by the transjugular route.Of the 27 liver biopsies done during the study period for unexplained acute or acute-on-chronic liver failure, SAH was found to be the etiology in nine cases.Nearly one-thirdcases of cryptogenic ACLF turned out to be SAH after liver biopsy.Histological features were similar in almost all biopsies (Table 2), characterized by extensive bridging to sub-massive necrosis (Figure 1) with collagen deposition and early fibrosis in some cases.The portal and the necrotic areas showed moderate to dense infiltrates of mixed inflammatory cells (Figure 2) including plasma cells and eosinophils. Occasional ill-defined lymphoid aggregates and venulitis were noted in one biopsy.Large areas of parenchymal necrosis with dense inflammatory infiltrate areconsidered characteristic of SAH[2,4,8,10,11]having excludedviral, ischemic and toxic causes.

Histopathology findings

In view of coagulopathy, liver biopsy could be performed in nine cases and was performed by the transjugular route.Of the 27 liver biopsies done during the study period for unexplained acute or acute-on-chronic liver failure, SAH was found to be the etiology in nine cases.Nearly one-thirdcases of cryptogenic ACLF turned out to be SAH after liver biopsy.Histological features were similar in almost all biopsies (Table 2), characterized by extensive bridging to sub-massive necrosis (Figure 1) with collagen deposition and early fibrosis in some cases.The portal and the necrotic areas showed moderate to dense infiltrates of mixed inflammatory cells (Figure 2) including plasma cells and eosinophils. Occasional ill-defined lymphoid aggregates and venulitis were noted in one biopsy.Large areas of parenchymal necrosis with dense inflammatory infiltrate areconsidered characteristic of SAH[2,4,8,10,11]having excludedviral, ischemic and toxic causes.

Autoimmune markers

The approach to diagnosis of SAH in each patient is described in Table 1.The median serum IgG was 2135 mg/dl (range: 1122– 5490 mg/dl). Although three patients had IgG levels within normal range (800–1700mg/dL), two of them had characteristic biopsy findings and one had significant autoantibody levels. Significant levels of autoantibodies were seen in all patients except one who had characteristic biopsy findings. When we calculated the simplified AIH score,12 only two patients had a score belowfive,due to low IgG levels but had excellent response to steroids with a follow-up atsix and 12 months yielding good clinical and biochemical remission.

Steroid therapy

Steroid therapy (prednisolone) was started after excluding bacterial infections by negative blood, ascitic fluid, and urine cultures, normal chest X-rays and when there was no clinical suspicion of sepsis or tuberculosis. In one patient it was started after a successful course of antibiotics for urosepsis. Steroids were initiatedwith antibiotic prophylaxis in all patients at a dose of 1mg/kg. When there was no response, it was increased to 2 mg/kg. Tacrolimus and mycophenolate were used when there was no response to high dose steroids.

Response to steroid therapy

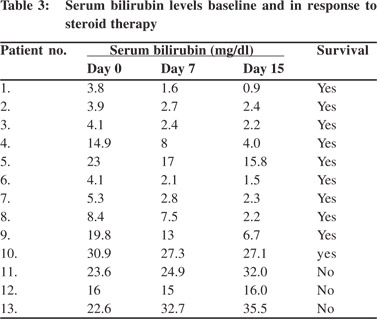

Liver function tests were performed on day 7 and every week at least for 3–4 weeks and thereafter as clinically indicated. Steroid therapy was managed and tapered as per the clinical and biochemical response in every patient. Ten patients responded very well to steroid therapy. Early reduction (ER), defined as reduction in serum bilirubin within 7-15 days of starting steroids,was seen in all the survivors byseven days. The median reduction in bilirubin was 2.3mg/dl (range: 0.9to 6.9) (Table 3). In one patient with only a small reduction in serum bilirubin on day 7, significant improvement in AST,ALT and PT-INR were seen. A further drop in serum bilirubin was seen by day 15 in all patients and the positive trend continue thereafter. By median 4.5 months (range: 2–6 months) liver function test normalized in all survivors.The survivors were followed up for median 13 months (range: 6–30 months),showing excellent clinical and biochemical response. Steroids were tapered and a dose of 5–10mg wascontinuedas maintenance dose. During steroid tapering, azathioprine was added in all the patients at a dose of 1–1.5mg/kg and continued thereafter.

Side effects of steroid therapy in responders

None of the responders suffered any major infective complication due to steroid therapy. One patient manifested steroid-induced psychosis which was easily managed with antipsychotics and steroid dose reduction.

Side effects of steroid therapy in responders

None of the responders suffered any major infective complication due to steroid therapy. One patient manifested steroid-induced psychosis which was easily managed with antipsychotics and steroid dose reduction.

Non-responders

Three patients did not respond to steroids and died without receiving a liver transplant. The median interval between presentation and death was 70days (range: 36–80 days). These patients either already have hepatic encephalopathy at admission or manifested it during hospital stay. Patient number 12, was enlisted for liver transplantation, and received steroids for only a week before she succumbed to bacterial sepsis and encephalopathy. Patient number 11, was continued on steroids for three weeks and her dose was increased to2mg/ kg.Tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were also added when high dose steroids failed to elicit any beneficial response. She eventually developed cellulitis in her right hand, and bilateral pneumonia and succumbed to her illness.For patient number 13, steroids were continued for four weeks but tapered thereafter as she developed bacterial sepsis and cytomegalovirus (CMV)viremia. All these patients did not show any early reduction in their serum bilirubin. On the contrary their serum bilirubin increased furtherby as early as day 7 (Table 3).Though patient number 12 showed a slight reduction of 1 mg/dl by day 7, the improvement was not sustained and the PT-INR continued to worsen. It is noteworthy that all SAH patients without hepatic encephalopathyshowed prompt response to steroids.

Other differences between survivors and nonsurvivors

Comparison of presenting features between survivors and nonsurvivors revealed that median serum bilirubin at admission was 6.8mg/dl (range: 3.8–30.9 mg/dl) in survivors as compared to 22mg/dl (range: 16-23.6 mg/dl) in those who died. In addition, all the non-survivors were females, two below the age of 20 and had grade 4 encephalopathy.We failed to find any difference in liver biopsy findings between these two groups. Rather than any differences in static parameters, early reduction in serum bilirubin(by 7-15 days) in response to steroid therapy, a dynamic factor,showed different trends between survivors and non-survivors

Discussion

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver with a spectrum of presentation varying from totally asymptomatic patients on one hand to sever liver failure on the other.[1,5] The severe presentation (SAH) may resemble ALF due to an abrupt onset new disease or a spontaneous flare of preexisting chronic inflammation manifesting as ACLF.[1–4] Czaja defined SAH as “a disease in which hepatic encephalopathy develops within 26 weeks of symptomatic onset or disease discovery with or without cirrhosis”.[5] But there is no consensus statement available from the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) to define SAH.It has been agreed that SAH represents a variant of AIH that has not been defined by the current guidelines laid down by the AASLD or EASL.[8] It is also evident from the literature that clinicopathological features of SAH are different from classical AIH and a high clinical suspicion is necessary for timely diagnosis and treatment.

All our patients presented with acute jaundice and features of liver failure (coagulopathy, ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy) in the absence of viral or toxic causes thus qualifying for the diagnosis of SAH. There is no information from India on this variant of AIH. In fact, there is no consensus on the guidelines of AIH in non-white population.[8] It is noteworthy that six patients had hepatic encephalopathy during the course of the disease qualifying for the definition of fulminant AIH. Three of these patients survived on steroid therapy whereas three others succumbed without showing any response to steroids. This emphasizes the importance of offering a steroid trial to even those with fulminant AIH. It is also noteworthy that hepatic encephalopathy was absent in 7/10 steroid responders. Among these 13 patients, seven had all three features of SAH namely, elevated IgG, significant auto antibodies and characteristic liver biopsy; four patients had two of the three features positive and only two patients were found positive for either the liver biopsy or autoimmune antibodies.

It is important to perform liver biopsy when SAH is suspected, as typical serological features of AIH can be absent in as many as 25-30% patients.[2,11] We found liver biopsy findings of multi-lobular collapse or extensive bridging necrosis with portal inflammation to be crucial for diagnosis of SAH even when auto antibodies were negative or IgG levels were low. Stravitz et al[2] found four features suggestive of autoimmuneacute liver failure (AI-ALF) among patients with indeterminate ALF including, massive necrosis, plasma cell rich infiltrate, perivenulitis and presence of lymphoid follicles.

All our patients had extensive parenchymal necrosis, with moderate to dense mixed inflammation with no definite histological features of chronicity, (except for focal portal fibrosis in two patients), even in patients with features of cirrhosis on USG. Presence of centrilobular necrosis and absence of typical features of AIH such as interface hepatitis have been well demonstrated by other investigators as well[10,11] and have recommended histology as an indispensable part of SAH diagnosis.Multilobular collapse has been uniformly associated with death in many cases.[11]

We also noted some interesting clinical observations very different from the western literature. Clinical presentation was different from our patientswith more frequent occurrence of ascites compared to hepatic encephalopathy.2–4 Our patients more commonly had subacute form of liver failure as described by Tandon et al.[13] Secondly, contrary to the common observation that AIH is more common in women and manifests with the typical phenotype of hyperglobulinemiaand autoantibodies, we encountered SAH in men aswell andwith significant autoantibodies.

Steroids are the mainstay of therapy in SAH as in chronic presentations. The response to steroids has been variable from 30-100%.[3,5,14] In sub-fulminant presentations such as that seen in our patients with acute onset jaundice, coagulopathy and ascites, it is reasonable to consider a trial of steroids. If successful, steroid therapy may obviate the need for liver transplantation that is beyond the reach of the majority of patients in developing countries. At the same time, prolonged futile therapy with steroids is likely to predispose to sepsis and make subsequent transplantation impossible. Thus, a more difficult decision is when to stop expecting a miracle and decide to go ahead with liver transplant.[9] Ideallya trial of steroid therapy needs to undertaken while an SAH patient is on the transplant waiting list. In our study, 77% patients responded to steroids and a reduction in serum bilirubin by day 7 was definitely associated with excellent short and long term outcome in all the responders. Yeoman et al have reported response rates(72%) similar to ours, with steroid therapy in acute icteric AIH.[14]They found baseline serum bilirubin at presentation and its reduction by day 7 markedly different between survivors and non-survivors. Treatment failure as predicted by failure in improvement of MELD or UKELD by day 7 was closely associated with mortality and need for emergency transplantation.[14] Biochemical improvement after two weeks of steroid therapy assured immediate survival in a cohort of SAH and non-improving bilirubinemiaby two weeks along with multilobular liver necrosis predicted mortality.[10] Lack of early serum bilirubin reduction by day 7 was synonymous with unsuccessful response to steroids, consistent with other studies.[3,14,15] This should be a warning signaling unabated liver cell necrosis and lack of control of inflammation by steroid therapy. We found improvement in PT-INR, ALT and AST even in non-responders, though reduction in bilirubin was characteristically seen only in responders. We suggest that the use of steroid therapy should be response guided as in the Lille model for alcoholic hepatitis.[16]

In steroid non-responders, dose escalation or addition of tacrolimus was not beneficial in our experience though Yeoman et al reported successful second line therapy in nine patients when there was treatment failure.[14] Since lack of early serum bilirubin reduction was also associated with sepsis in addition to poor survival, we suggest cessation of steroids and no addition of second line immunosuppressive therapy in such patients, and an early enlistment for liver transplant as a lifesaving measure.

In summary, clinical suspicion supported by characteristic liver biopsy findings and autoimmune serology led to the diagnosis of SAH in a cohort of patients with unexplained liver failure.Corticosteroid therapy was successful in majority of these patients with excellent short and long term results, which could be predicted by early reduction in serum bilirubin within 7–15 days.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor George Kurian for his review of the manuscript and valuable suggestions.

References

- Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–213.

- Stravitz RT, Lefkowitch JH, Fontana RJ, Gershwin ME, Leung PS, Sterling RK, et al. Autoimmune acute liver failure: proposed clinical and histological criteria. Hepatology. 2011;53:517–26.

- Ichai P, Duclos-Vallee JC, Guettier C, Hamida SB, Antonini T, Delvart V, et al. Usefulness of corticosteroids for the treatment of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:996–1003.

- Kessler WR, Cummings OW, Eckert G, Chalasani N, Lumeng L, Kwo PY. Fulminant hepatic failure as the initial presentation of acute autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:625–31.

- Czaja AJ. Acute and acute severe (fulminant) autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:897–914.

- Bhatia V, Singh R, Acharya SK. Predictive value of arterial ammonia for complications and outcome in acute liver failure. Gut. 2006;55:98–104.

- Kaur S, Kumar P, Kumar V, Sarin SK, Kumar A. Etiology and prognostic factors of acute liver failure in children. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:677–9.

- Czaja AJ. Review article: the management of autoimmune hepatitis beyond consensus guidelines. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:343–64.

- Czaja AJ. Corticosteroids or not in severe acute or fulminant autoimmune hepatitis: therapeutic brinksmanship and the point beyond salvation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:953–5.

- Yasui S, Fujiwara K, Yonemitsu Y, Oda S, Nakano M, Yokosuka O. Clinicopathological features of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:378–90.

- Fujiwara K, Fukuda Y, Yokosuka O. Precise histological evaluation of liver biopsy specimen is indispensable for diagnosis and treatment of acute-onset autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:951–8.

- Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Pares A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–76.

- Tandon BN, Bernauau J, O’Grady J, Gupta SD, Krisch RE, Liaw YF, et al. Recommendations of the International Association for the Study of the Liver Subcommittee on nomenclature of acute and subacute liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:403–4.

- Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Zen Y, Maninchedda P, Portmann BC, Devlin J, et al. Early predictors of corticosteroid treatment failure in icteric presentations of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53:926–34.

- Czaja AJ, Rakela J, Ludwig J. Features reflective of early prognosis in corticosteroid-treated severe autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:448–53.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Diaz E, Fartoux L, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348–54.

|

|

|

|

|

|