|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Jitendra H Mistry, Vinay Kumaran, Vibha Varma, Sorabh Kapoor, Samiran Nundy, Naimish Mehta

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and

Liver Transplantation,

Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi-110060, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Jitendra H Mistry

Email: jitlap@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.170

48uep6bbphidvals|673 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Prolonged unilateral biliary obstruction or vascular occlusion can lead to atrophy of the ipsilateral lobe of liver with contralateral lobe hyperplasia. This is known as the ‘atrophyhypertrophy complex’ (AHC). In the absence of a gall bladder, this phenomenon can be missed on preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC). Performing a hepaticojejunostomy in the presence of AHC is technically difficult and is associated with greater blood loss and a higher incidence of stricture at the anastomotic site.[1] Hence preoperative diagnosis is important. We describe here a patient with AHC which went unrecognized during preoperative evaluation.

Case report

A46-year-old male patient who suffered an attack of acute cholecystitis 18 months earlier, underwent interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy five months ago. The operative procedure had been uneventful but on the second postoperative day, he had developed abdominal pain and non-bilious vomiting.

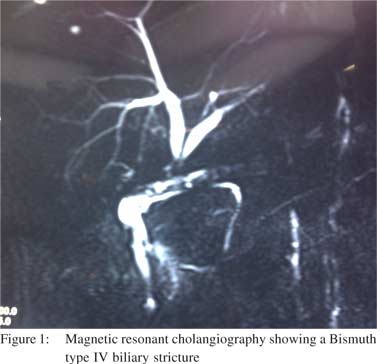

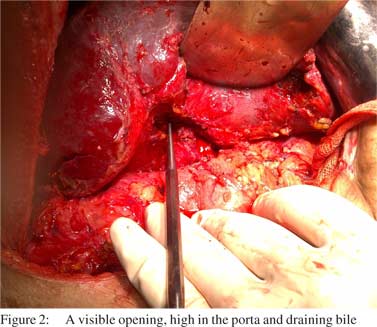

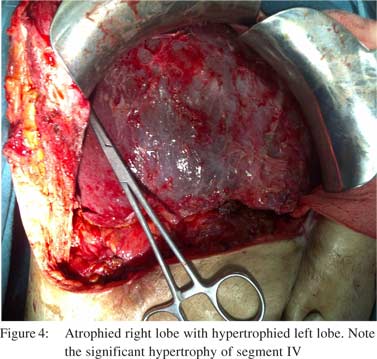

Ultrasound of the abdomen showed a collection in the right sub-hepatic space, which on aspiration was found to be bile. On the 10th postoperative day he had frank bilious discharge from a port site, had a high total leucocytic count and developed jaundice. He underwent another exploration, and a complete transection of the common bile duct (CBD) was found and the surgeon was unable to locate its proximal stump. An abdominal drain was placed in the right sub-hepatic space and he was referred to a higher centre. On admission to our hospital, the patient had signs of sepsis with tachycardia, dehydration, metabolic acidosis, acute renal failure and respiratory distress syndrome. The abdominal drainage was approximately 1000 ml of bile per day. He required ventilatory support, and dialysis for acute renal failure. Once his general condition stabilized, a CT scan was performed which revealed a residual abdominal collection and a percutaneous drain was placed. He was then discharged after 50 days in hospital, with a controlled biliary fistula and a plan for a definitive procedure at a later date. However during follow up, he developed repeated attacks of cholangitis. He was therefore readmitted five months after his index surgery, for a hepaticojejunostomy. A magnetic resonance cholangiogram (MRC) was performed which showed a Bismuth type IV biliary stricture (Figure 1). At operation, there were dense adhesions at the porta hepatis and the duodenum and hepatic flexure of the colon were adherent to the gall bladder fossa. There was an opening high up in the porta which was draining bile (Figure 2). Intraoperative cholangiography showed a picture which was similar to the MRC although the exact anatomy was unclear. So a marker was placed at the junction of the right and left lobe and the cholangiogram was repeated. This revealed no filling of the biliary tree on the right side of the marker (Figure 3). The junction of segment IV and segment II and III ducts had given the appearance of a right and left duct on MRC, mimicking a Bismuth type IV stricture. The right hepatic artery and right duct could not be traced. The left lobe of the liver was hypertrophied with an atrophied right lobe (Figure 4). In view of the atrophy-hypertrophy complex with a history of repeated attacks of cholangitis, a right hepatectomy and a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy with the left duct was performed. The total operative time was 11 hours and there was a blood loss of 1000 ml. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful and he was discharged on day seven. At six months follow up he was doing well.

Discussion

The incidence of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy varies from 0.2 to 0.6 %.[2] Ten percent of postcholecystectomy bile duct injuriesare associated with the atrophy-hypertrophy complex.[1] The mechanism of AHC is not well understood, but it usually develops with unilateral bile duct obstruction[3] or vascular occlusion4 or injury to both the duct as well as the blood vessels. It is not seen with isolated hepatic artery occlusion but is common with unilateral portal vein occlusion.[4]The ipsilateral atrophy due to bile duct obstruction occurs mainly due to apoptosis and the contralateral lobe hypertrophies due to hyperplasia.[5]There are important surgical implications of the AHC. In AHC due to right side bile duct injury, the left lobe hypertrophies with maximum enlargement occurring in segment IV, thereby obscuring the portal structures during surgery. The porta gets rotated anticlockwise, making the portal vein an anterior and the bile duct a posterior structure.

Discussion

The incidence of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy varies from 0.2 to 0.6 %.[2] Ten percent of postcholecystectomy bile duct injuriesare associated with the atrophy-hypertrophy complex.[1] The mechanism of AHC is not well understood, but it usually develops with unilateral bile duct obstruction[3] or vascular occlusion4 or injury to both the duct as well as the blood vessels. It is not seen with isolated hepatic artery occlusion but is common with unilateral portal vein occlusion.[4]The ipsilateral atrophy due to bile duct obstruction occurs mainly due to apoptosis and the contralateral lobe hypertrophies due to hyperplasia.[5]There are important surgical implications of the AHC. In AHC due to right side bile duct injury, the left lobe hypertrophies with maximum enlargement occurring in segment IV, thereby obscuring the portal structures during surgery. The porta gets rotated anticlockwise, making the portal vein an anterior and the bile duct a posterior structure.

All these changes make surgery more difficult and lead to greater blood loss and higher postoperative complications. Thus in our case the operating time was 11 hours and the patient lost 1000 ml of blood.

Recognition of AHC preoperatively is important for planning proper treatment. Ultrasound can detect AHC, but is operator dependent. Computed tomography or nuclear scintigraphy may be helpful,[6] but these studies are not routinely employed to evaluate postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. In the postcholecystectomy patient, it thus becomes difficult to diagnose AHC preoperatively as happened in our case. On MRC the ducts of the hypertrophied left lobe can mimic the main right and left hepatic ducts. The management of AHC is controversial. Drainage of the bile duct of the atrophied segment does not reverse the atrophy,[7] but Pottakkat et al reported reversal of biliary cirrhosis after such drainage.[1] Hadjis et al reported successful expectant management in three patients with a unilateral hepatic duct stricture with liver atrophy.[8]

However if the ipsilateral bile duct is not found or the atrophied lobe is unhealthy and the patient has a history of recurrent cholangitis he may require a formal anatomical hepatectomy.

References

- Pottakkat B, Vijayahari R, Prasad KV, Sikora SS, Behari A, Singh RK, et al. Surgical management of patients with postcholecystectomy benign biliary stricture complicated by atrophyhypertrophy complex of the liver. HPB (Oxford).2009;11:125–9.

- McPartland KJ, Pomposelli JJ. Iatrogenic biliary injuries: classification, identification, and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1329–43; ix.

- Hadjis NS, Schweizer W, Blumgart LH. Liver hyperplasia, hypertrophy and atrophy: clinical relevance. In: Blumgart LH, Fong Y, editors. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;1994.p.83–94.

- Hatakeyama Y, Asanuma Y, Sato T, Koyama K. Regional and general effects of hepatic lobes with impaired blood flow after hepatic resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:487–91.

- Cha C, Blumgart LH. Liver hyperplasia, hypertrophy and atrophy In:Blumgart LH, Belghiti J, Jarnagin WR, Chapman WC,Buchler MW, Hann LE, et al, editors. Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. 4th ed. Saunders Elsevier;2007.p.63–71.

- Czerniak A, Soreide O, Gibson RN, Hadjis NS, Kelley CJ, Benjamin IS, et al. Liver atrophy complicating benign bile duct strictures. Surgical and interventional radiologic approaches. Am J Surg. 1986;152:294–300.

- Fansto NS, Hadgjis NS, Fong Y. Liver hyperplasia, hypertrophy, atrophy, and molecular basis of liver regeneration. In: Blumgart LH, Fong Y, editors. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. 3rd ed. London: WB Saunders; 2000.p.73.

- Hadjis NS, Carr D, Blenkharn I, Banks L, Gibson R, Blumgart LH. Expectant management of patients with unilateral hepatic duct stricture and liver atrophy. Gut. 1986;27:1223–7.

|

|

|

|

|

|