|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Tarun Rustagi1, Murtuza Rampurwala1, Mridula Rai1, Sharon Fuentes2, Michael Golioto3

Department of Internal Medicine1

University of Connecticut Health Center,

Farmington and

Department of Pathology2, and

Division of Gastroenterology3,

Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Tarun Rustagi

Email: tarun.rustagi@yale.edu

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.134

48uep6bbphidvals|619 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Case report

A 66-year-old man presented with intermittent upper abdominal pain (epigastralgia) for a few months associated with heartburn, intermittent nausea and bloating. The patient denied vomiting, dysphagia or odynophagia. There was no history of significant weight loss, anorexia, overt gastrointestinal bleeding or alterations in bowel movements. His past medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypothyroidism. He was a former smoker with 20 pack-year smoking history, and drank alcohol occasionally. Family history was notable for his sister and two nieces with breast cancer. The patient’s symptoms were attributed to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and were empirically treated with proton pump inhibitor (PPI)—omeprazole. However, his symptoms continued to worsen and he was referred for endoscopic evaluation. Physical examination was significant only for mild epigastric tenderness. There was no hepatosplenomegaly, ascites or lymphadenoapthy. Initial laboratory investigations were unremarkable.

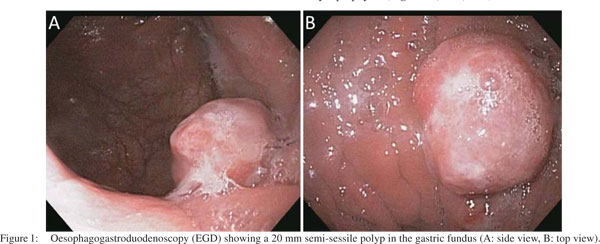

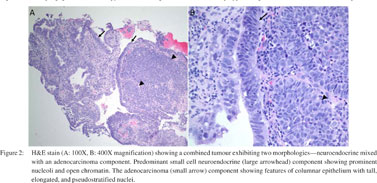

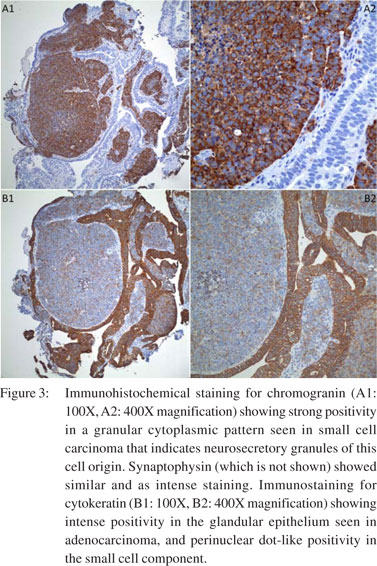

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed, which revealed a 20 mm semi-sessile polyp on the greater curvature in the fundus of the stomach (Figure 1). Histopathology of the gastric biopsies from this polypoid mass showed solid proliferation of small-sized tumour cells with scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei, positive for immunostaining with anti-chromogranin A and antisynaptophysin (Figures 2, 3A1, 3A2). There was also a minor component of neoplastic cells with gland formation being positive for anti-cytokeratin (Figures 2, 3B1, 3B2). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of combined gastric small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma–adenocarcinoma was established. Immunostaining for MIB1 showed high proliferation index in both the neoplastic components. Subsequent, computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed a 2 cm polypoid mass in the gastric fundus with enlarged regional lymph nodes (largest 3 cm coeliac lymph node, , but no evidence of visceral metastasis or disseminated disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not show metastasis. A positron emission tomography (PET)- CT scan showed no focal [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the stomach, or lymph nodes and no other focus of the disease.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy and surgical resection was planned. He has completed four out of total six cycles of combination chemotherapy consisting of etoposide 100 mg/m2 on days 1–3 and carboplatin AUC-5 on day 1 of a 28-day cycle. Follow-up imaging showed significant Figure 3: Immunohistochemical staining for chromogranin (A1: 100X, A2: 400X magnification) showing strong positivity in a granular cytoplasmic pattern seen in small cell carcinoma that indicates neurosecretory granules of this cell origin. Synaptophysin (which is not shown) showed similar and as intense staining. Immunostaining for cytokeratin (B1: 100X, B2: 400X magnification) showing intense positivity in the glandular epithelium seen in adenocarcinoma, and perinuclear dot-like positivity in the small cell component. regression of abdominal lymphadenopathy and the gastric mass was no longer visible. The patient reported symptomatic improvement and continues to do well without any complications.

Discussion

Small cell carcinomas (SmCC) are among the most aggressive, poorly differentiated and highly malignant of the neuroendocrine tumours (NETs).[1] SmCC predominantly affect the lung; only about 5% of SmCC have an extrapulmonary origin.[2] Extrapulmonary SmCC have been reported in various organs such as the oesophagus, colon, rectum, pancreas, uterine cervix, urinary bladder, prostate, kidneys and salivary glands.[3] Primary SmCC areextremely rare in the stomach, representing <0.1% of all primary gastric cancers.[4] A majority of the cases have been reported among Asians with a minority of case reports from western countries. These occur more frequently in the sixth to seventh decade of life and in men.[2]

The most frequent location in the stomach is the upper third (45.2%), followed by the antrum (35.2%) and middle third (19.2%).[2] Progressive dysphagia and weight loss are often the first symptoms of the disease, similar to other gastric malignancies. In the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of gastrointestinal tumours, SmCC of the stomach have been recognized as an “independent entity affecting the stomach”. There are two types of SmCC—a “pure type” and a “composite or combined-type” admixing glandular and/or squamous differentiation. In the reported cases, a higher prevalence of “pure-type” (60%) than “composite-type” (40%) have been found.[2]

The exact histogenesis of SmCC of the stomach remains unclear. It has been proposed to originate from either the argyrophilic Kulchitsky cells found in the bronchial and gastric mucosa (amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation [APUD] cells) or from an endodermal origin.[2] Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD56 and other immunohistochemical markers have been described as reliable markers for detecting neuroendocrine differentiation. the CD56 marker is also helpful in differentiating between SmCC and large cell carcinomas.[4] The biological features of gastric SmCC resemble those of pulmonary SmCC, which is consistent with the histological and immunohistochemical similarity of the two tumours.[2] Gastric SmCC has a poor prognosis with a mean survival of 7 months.[5] This neoplasm shows a high propensity to distant metastasis and locoregional involvement.[1] The choice of treatment for gastric SmCC remains controversial. The surgical approach follows the same criteria of adenocarcinoma as it is linked to the primary tumour location in the stomach.[2] Because of similarity in the biological and clinical characteristics of gastric and pulmonary SmCC, some authors affirmed that the validity of chemotherapy with a regimen specific for pulmonary SmCC may be suitable for the treatment of this tumour.[5] The combination chemotherapy usually consists of cisplatin and etoposide or irinotecan.[2] Multimodality approaches are promising but more studies are needed before any single combination can be recommended.[1]

References

- Richards D, Davis D, Yan P, Guha S. Unusual case of small cell gastric carcinoma: case report and literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:951–7.

- Cioppa T, Marrelli D, Neri A, Caruso S, Pedrazzani C, Malagnino V, et al. A case of small-cell gastric carcinoma with an adenocarcinoma component and hepatic metastases: treatment with systemic and intra-hepatic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16:453–7.

- Han B, Mori I, Wang X, Nakakura M, Nakamura K, Kakudo K. Combined small-cell carcinoma of the stomach: p53 and K-ras gene mutational analysis supports a monoclonal origin of three histological components. Int J Exp Pathol. 2005;86:213–18.

- Shpaner A, Yusuf TE. Primary gastric small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2007;39:E310–E311.

- Iwamuro M, Tanaka S, Bessho A, Takahashi H, Ohta T, Takada R, et al. Two cases of primary small cell carcinoma of the stomach.Acta Med Okayama. 2009;63:293–8.

|

|

|

|

|

|