|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Nontraumatic perforation, colon, tuberculosis, amoebiasis |

|

|

Komal Singla, Garima Mahajan, Sarla Agarwal, Sonal Sharma

Department of Pathology,

University College of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Sonal Sharma

Email: sonald76@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.68

Abstract

Aim: Nontraumatic perforation of colon is an uncommon cause of peritonitis requiring early surgical intervention. This study was carried out to determine the prevalence patterns of the different etiologies of nontraumatic perforation of colon.

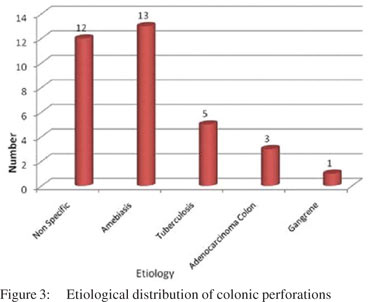

Methods and results: A total of 35 patients with segments of colon or perforation margins removed for perforation were included. Most of the perforations occurred in the caecum, of which two were seen at the ileocaecal junction. The commonest cause was infection (amoebiasis :13 cases and tuberculosis : 5 cases) followed by ulcers of non specific ulcers (12 cases). There were three cases of adenocarcinoma causing secondary perforation and one case of idiopathic intestinal gangrene and volvulus each.

Conclusion: In tropics, non traumatic perforations of colon most often involves caecal and ileocaecal segment and the most common etiology is amoebiasis.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|553 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Peritonitis secondary to perforating lesions of the colon affect a heterogeneous group of patients and usually present as abdominal emergencies with high morbidity and mortality. Various etiologies have been suggested for colonic perforations; however, the distribution of these etiologies across the globe is variable. In the western world, colorectal cancer, diverticulitis, trauma and vascular disorders[1] predominate as the etiology of colonic perforation whereas amoebiasis and tuberculosis are more common in developing countries. With the aim of evaluating the prevalence pattern of various etiologies, we analyzed our experience of nontraumatic colonic perforations over a period of two years.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted at the Department of Histopathology of our Institute from March 2009 to March 2011. Records of patients surgically operated for large bowel perforations in our hospital were reviewed. Cases in which only ulcer edge biopsies were taken were also included in this s tudy. Cases with traumatic perforation were excluded from this study. The specimens were received in 10% buffered formalin. The lymph nodes were dissected from the specimen and examined. Appropriate sections were taken from pathological lesions and randomly from other sites of the bowel. Sections were processed routinely and embedded in paraffin and stained routinely with hematoxylin and eosin and special stains as appropriate.

Results

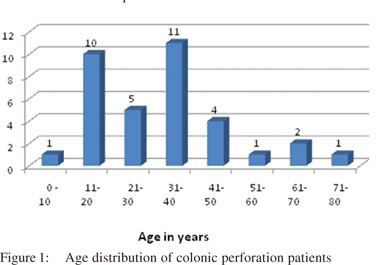

A total of 35 patients were included in this study, of which 26 were males and nine were females. There was a wide range of age distribution, the youngest being a 6-year-old male child and the oldest being an 80-year-old female. In the present study, the most commonly affected age group was 31-40 years (Figure 1). In 32 cases, bowel segments were submitted for examination whereas perforation edge biopsies were examined in rest of the three cases.

The most common presenting complaints of patients were abdominal pain, diarrhea with or without blood, vomiting, anorexia, fever and weight loss. One case had past history of pulmonary tuberculosis and one patient was already on antitubercular treatment. On physical examination, all patients showed signs of abdominal tenderness, while signs of peritoneal irritation (e.g. muscular guarding, rebound tenderness) were recorded in only half of the patients. Abdominal distension was another common finding. Multiple air-fluid levels on abdominal X-ray in erect position were evident in 50% of cases. Only nine cases had a definitive preoperative diagnosis.

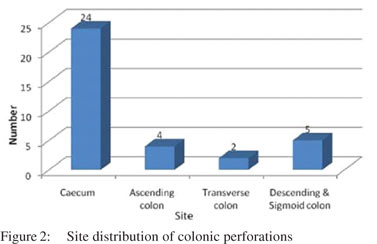

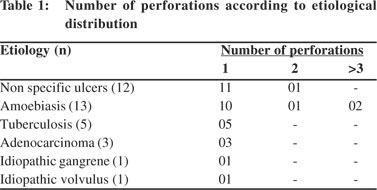

The distribution of the anatomic sites of the perforations is given in Figure 2. Most of the perforations occurred in the caecum of which two were seen at the ileocaecal junction, followed by descending and sigmoid colon. Ascending colon showed perforations in four cases and transverse colon in two cases. One case had perforation both in caecum and transverse colon. On gross examination of the bowel segments, majority of segments showed single perforation while multiple perforations were seen in caecum in four cases only. The distribution of number of perforations seen in particular etiology has been charted in Table 1.

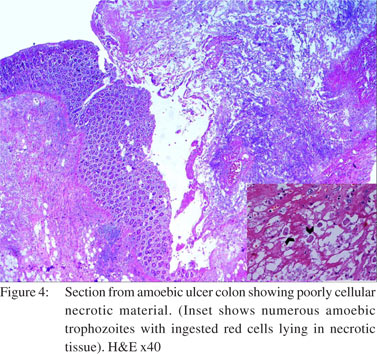

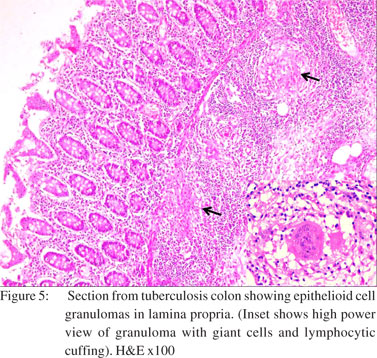

Two cases showed strictures along with perforation. Both of them showed nonspecific perforation peritonitis on histopathological examination. Colonic segments were distended, thin-walled, and frankly gangrenous in two cases. Lymph nodes could be dissected out in nine cases. Histological examination revealed that maximum number of cases (n=12) had nonspecific features like inflammatory granulation tissue, serositis and foreign body giant cell reaction (Figure 3). Amongst the cases where a definitive opinion could be given, most were diagnosed as intestinal amoebiasis (n=13), followed by tuberculosis (n=5). Segments with amoebic perforation showed undermining flask shaped ulcers containing amoebic trophozoites (Figure 4). Cases with tuberculosis showed epithelioid cell granulomas with few showing caseous necrosis (Figure 5). Ziehl Neelsen stain showed AFB (acid fast bacilli) in 3/5 cases. The AFB seen were solid, fragmented or beaded rods present in the granuloma in association with the epithelioid cells as well as in the caseous areas. The findings in lymph nodes in three cases of tuberculous etiology, supplemented those of the intestinal segment. In rest of the cases, lymph nodes showed reactive hyperplasia.

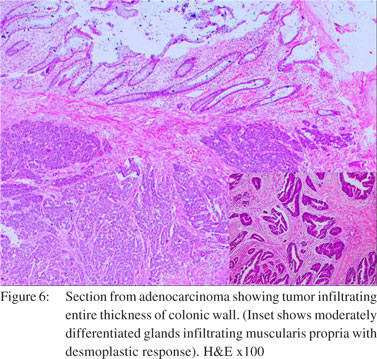

There was one case of well differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma, TNM stage IIB and another of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, TNM stage IIC, both in the sigmoid colon with tumor perforation at the site of neoplasm. A third case of adenocarcinoma rectum showed a single perforation proximal to the neoplasm in the sigmoid colon. All cases showed irregularly shaped glands of variable sizes and highly pleomorphic cells infiltrating the wall of intestine reaching up to the serosa (Figure 6). Lymph node involvement (1/3) was seen in one of the cases. The third case belonged to TNM stage IIIB or Duke’s C.

Ischemic necrosis of variable extent was seen in the intestinal segment involved by gangrene. The patient with gangrenous bowel was a 37-year-old male. A single case of volvulus was diagnosed on gross examination in a 45-year-old female, mainly involving the sigmoid colon. Histopathological examination of both the cases showed similar findings. There was thickening of the arterial walls. Few thrombotic vessels were also seen.

Discussion

A wide range of etiologies have been proposed for large bowel perforation. In tropical countries like ours the main etiology of large bowel perforation remains infection apart from perforation peritonitis due to nonspecific causes. In a previous study by the authors on the role of ulcer edge biopsy in diagnosing nontraumatic perforation of small intestine, it was found that TB and typhoid are the most common etiologies in developing countries.[2] The Western literature describes colorectal cancer as the most common cause for perforation followed by benign causes such as diverticulitis, trauma and vascular disorders.[1]

The site of perforation commonly seen in Western countries is the sigmoid colon1 whereas caecal perforations were common in our study. Large bowel perforation seems to be more common in elderly patients in Western studies. In a study by Bielecki et al[1] the age of patients ranged from 35 to 95 years (mean: 61.3±15.2 years). In our study, the majority of patients were young adults. This may be due to a difference in etiology of perforation in our study from the Western world. Amoebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the protozoon, Entamoeba histolytica which infects 10% of the world’s population, resulting in 100,000 deaths per year.[3] The prevalence of the disease has been reported to be as high as 50% in the Indian subcontinent[4] as compared to the West.[5] While asymptomatic E. histolytica infection is equally distributed between the sexes, reports of invasive amoebiasis show a higher prevalence among men than women.[6] Invasive amoebiasis (dysentery, liver abscess, colonic perforation, peritonitis, appendicitis and amoeboma) occurs typically between 30 to 60 years of age.[7] The present study showed amoebiasis as the most common cause of colonic perforation. Out of 13 cases with amoebic colitis, twelve presented with caecal perforation and one case presented with a sigmoid colon mass. In Barker’s autopsy study of patients with amoebic colitis, perforations were found in 30.4% cases only.[8] Chen et al[9] described eight patients with free intraperitoneal perforations. One of our cases showed a localized mass in the sigmoid colon which was clinically mistaken as carcinoma colon. Amoeboma refers to an inflammatory tumoral mass or thickening associated with an infection of E. histolytica that might occur anywhere in the large bowel. The difficulty in differentiating an amoeboma from a carcinoma has long been recognized.[10]

The colon and liver are the principal organs affected in amoebiasis. Invasion of the colonic mucosa leads to dissemination of the organism to extracolonic sites, predominantly the liver. Infection by E. histolytica causes a spectrum of intestinal illnesses from asymptomatic infection, symptomatic noninvasive infection, acute protocolitis (abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, fever, weight loss and dehydration), to fulminant colitis with perforation[11] which carries a mortality rate of 50% or greater.[12] The trophozoite form of the amoeba has the capacity to invade the bowel mucosa. Cysts in the faeces transmit infections between humans. Toxins present in the organism’s microfilament, a membrane phospholipase and a phosphoglutamase, which cause mucosal defects, account for the invasive capacity of E. histolytica.[13,14] It has been suggested that the parasite invades the nutrient arterioles with subsequent occlusion and ischemia of the bowel wall, resulting in progression of the initial superficial ulceration to transmural necrosis and perforation.[15]

Grossly, the bowel segments were ulcerated and friable. Single perforations were more common except in three cases which showed two perforations each. In our study the perforations were most commonly found in the caecum whereas Ozdogan et al[16] noted rectum as the most common site for amoebic perforations. Typical colonic perforations vary in size from pinhead to 2–4 cm.[17] Colonic perforation (0.5–5% of cases) can present acutely with a drastic deterioration in a patient’s condition or as a slow leakage.[18,19] Histopathology showed multiple flask shaped ulcers, which extended into the mucosa, submucosa and inner portion of the muscularis propria containing polymorphs, fibrin, mucus and numerous unicellular organisms with features of amoebic trophozoites. The trophozoites were the size of macrophages and possessed small, eccentric, eosinophilic, round nuclei with abundant eosinophilic PAS-positive cytoplasm. The ulcers were bordered by inflamed granulation tissue and the adjacent mucosa was oedematous and chronically inflamed. The lymph nodes removed in four cases showed reactive hyperplasia. Subsequent to this, anti-amoebic treatment was commenced using intravenous metronidazole in cases without preoperative diagnosis of amoebic colitis.

The next common category is perforations of nonspecific etiology (12 cases including three cases of perforation edge biopsy) seen mainly in the caecum. The histopathological examination of these nonspecific perforations showed an ulcer base which was formed by granulation tissue and fibrinopurulent exudate. This was usually accompanied by foreign body giant cell reaction and serositis. However, a nonspecific diagnosis can still not rule out the possibility of infectious etiology in cases of perforation edge biopsies because of focal involvement of the disease. The patients were given a course of antibiotics in the postoperative period as per culture and sensitivity reports and were advised follow up in outpatient department. Tuberculous perforation formed the next frequent category. The perforation due to abdominal tuberculosis is supposed to be uncommon because of reactive thickening of he peritoneum and formation of adhesions with surrounding tissues. Tuberculosis may involve any site of the gastrointestinal tract, but the commonest site of involvement is the ileocaecal region.[20] An increased incidence of perforation has been observed in patients taking anti-tubercular chemotherapy. This is presumably due to a reduced inflammatory response which leads to poor healing of ulcers and a reduced tendency of reinforcement by the mesentery.[21,22] In the present study five cases (14.28%) of tuberculosis were seen, out of which two had caecal perforations and three had perforations in the ascending colon. Histopathology of the intestinal segments revealed epithelioid cell granulomas with or without caseous necrosis. The histopathology of associated lymph nodes dissected out in two cases was consistent with tuberculosis.

Subsequent to histopathologic diagnosis, patients were started on a standard four-drug anti-tubercular treatment (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) for four months, followed by a two drug treatment (isoniazid and rifampicin) for two months.

Three patients (8.5%) of adenocarcinoma colon in our series showed tumor perforations in the sigmoid colon, which is in concordance with previous studies where the incidence of such perforation ranged from 2.6%23 to 10%.24 In adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum, obstruction and perforation may occur either alone or together at the site of the neoplasm or proximally. Both events carry a poor prognosis. Two cases in this study had the perforation and mass at the same site and one had perforation proximal to the neoplasm. The perforation of colorectal carcinoma can occur because of direct perforation from tumor necrosis or because of proximal colon blow-out from an obstructing tumor. Previous studies have found that obstruction and perforation tend to occur in the older age groups.24,25 Our study was also in agreement with this observation.

In this study, we found that colonic perforation in developing countries can be due to infection particularly, amoebiasis and few cases of malignancy. Although amoebic colitis perforation is an infrequent entity even in endemic regions, it is associated with a high mortality rate. Because the diagnosis is frequently delayed or made when the peritonitis has already occurred, it is important to treat every patient promptly when the diagnosis is suspected. In conclusion, diagnosis of large bowel perforation is a challenge preoperatively. Clinical findings especially in amebic colitis are usually nonspecific and definite diagnosis can be reached only after histopathology. We advocate a high index of suspicion to prevent diagnostic delays and high mortality.

References

- Bielecki K, Kaminski P and Klukowski M. Large bowel perforation: morbidity and mortality. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:177–82.

- Sharma S, Kotru M, Batra M, Gupta A, Rai P and Sharma R. Limitations in the role of ulcer edge biopsy in establishing the aetiology of nontraumatic small bowel perforation. Trop Doct. 2009;39:137–41.

- Reed SL. Amebiasis: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:385–93.

- Ravdin JI. Amebiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1453–64.

- Larsson PA, Olling S and Darle N. Amebic colitis presenting as acute inflammatory bowel disease. Case report. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:553–5.

- Acuna-Soto R, Maguire JH and Wirth DF. Gender distribution in asymptomatic and invasive amebiasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1277–83.

- Cardoso JM, Kimura K, Stoopen M, Cervantes LF, Flizondo L, Churchill R, et al. Radiology of invasive amebiasis of the colon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;128:935–41.

- Barker EM. Colonic perforations in amoebiasis. S Afr Med J. 1958;32:634–8.

- Chen WJ, Chen KM and Lin M. Colon perforation in amebiasis. Arch Surg. 1971;103:676–80.

- Harris HF. Amoebic dysentery. Am J Med Sci. 1898;115:384–413.

- Wanke C, Butler T and Islam M. Epidemiologic and clinical features of invasive amebiasis in Bangladesh: a case-control comparison with other diarrheal diseases and postmortem findings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:335–41.

- Patterson M and Schoppe LE. The presentation of amoebiasis. Med Clin North Am. 1982;66:689–705.

- Aristizabal H, Acevedo J and Botero M. Fulminant amebic colitis. World J Surg. 1991;15:216–21.

- Luvuno FM, Mtshali Z and Baker LW. Vascular occlusion in the pathogenesis of complicated amoebic colitis: evidence for an hypothesis. Br J Surg. 1985;72:123–7.

- Ozdogan M, Baykal A and Aran O. Amebic perforation of the colon: rare and frequently fatal complication. World J Surg. 2004;28:926–9.

- Mukerjee S and Nigam M. Amoebic perforations of the colon. Am J Proctol. 1975;26:57–64.

- Adams EB and MacLeod IN. Invasive amebiasis. I. Amebic dysentery and its complications. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:315–23.

- DeSa AE. Surgical amoebiasis. Prog Drug Res. 1974;18:77–90.

- Kakar A, Aranya RC and Nair SK. Acute perforation of small intestine due to tuberculosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1983;53:381–3.

- Seabra J, Coelho H, Barros H, Alves JO, Goncalves V and Rocha- Marques A. Acute tuberculous perforation of the small bowel during antituberculosis therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:320–2.

- Smith H. Paradoxical responses during the chemotherapy of tuberculosis. J Infect. 1987;15:1–3.

- Crowder VH, Jr. and Cohn I, Jr. Perforation in cancer of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1967;10:415–20.

- Mandava N, Kumar S, Pizzi WF and Aprile IJ. Perforated colorectal carcinomas. Am J Surg. 1996;172:236–8.

- Kyllonen LE. Obstruction and perforation complicating colorectal carcinoma. An epidemiologic and clinical study with special reference to incidence and survival. Acta Chir Scand. 1987;153:607–14.

- Runkel NS, Schlag P, Schwarz V and Herfarth C. Outcome after emergency surgery for cancer of the large intestine. Br J Surg. 1991;78:183–8.

|

|

|

|

|

|