|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

biliary pancreatitis, recurrent pancreatitis, women, gallstones, microlithiasis |

|

|

Rey Romero-González,1 Arnoldo Garza-Garza,2 Laura Martinez Perez-Maldonado,3 Raymundo Romero-González,4 José Pulido- Rodriguez,2 Felipe González-Velázquez6

Department of Surgery, Programa

Multicéntrico SSNL/ITESM,1

Department of Surgery, SSNL,2

Medical School, ITESM,3 Medical

School, UANL,4

Monterrey, NL, México.

División de Investigación ,UMAE,5

Hospital de Especialidades # 14,

IMSS,

Veracruz, Ver. México.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Rey Romero-González

Email: rey_@hotmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.69

Abstract

Background and aim: Recurrent biliary pancreatitis is described as episodes of new abdominal pain after diagnosis of pancreatitis. Few studies have analyzed the abdominal pain before the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Our study aimed to analyze factors associated with previous abdominal pain episodes in patients with biliary pancreatitis, and elucidate its possible pancreatic origin.

Methods: Data from direct interrogation and medical records was analyzed from 48 hospitalized female patients with diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis.

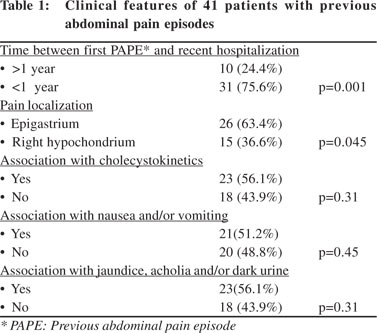

Results: Mean age of our patients was 31.6 years (SD+13.9). Forty one (85.4%) patients gave history of at least one previous abdominal pain episode. During the episode 37 (90.2%) patients received H2 receptor antagonist or proton pump inhibitors as treatment; 26 (63.4%) had epigastric pain; 23(56.1%) gave association with cholecystokinetic food; 21 (51.2%) complained of nausea and/or vomiting; 23 (56.1%) had jaundice, acholia and/or dark urine; and 20 (48.9%) patients had microlithiasis and/or biliary sludge.

Conclusions: Previous abdominal pain episodes had similar characteristics to a pancreatic

episode in a high percentage of our patients. These characteristics suggest that these episodes are often undiagnosed pancreatic attacks.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|554 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common problem with an annual incidence of 5 to 80 per 100,000 of the general population. Many causes have been proposed, but the pathogenesis remains controversial. The most common cause of AP is biliary pancreatitis, wherein gallstones obstruct the distal common bile-pancreatic duct, although the mechanism by which this induces pancreatitis is unknown.[1] Possible risk factors for biliary pancreatitis include male gender and stone size, but it occurs more frequently in women due to a higher prevalence of gallbladder disease.[2] The diagnosis of biliary pancreatitis is based on clinical assessment, laboratory assessment and radiological tests. The gold standard for management of biliary pancreatitis is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[3] Numerous scales are used to predict prognosis. Imrie and Ranson’s criteria provides a simple method for assessing severity. APACHE II and Balthazar are more complex and expensive methods but have a very high sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy.[4,5] Recurrent pancreatitis in the setting of gallstones has been described in a low percentage of patients. In these cases the patients are diagnosed with acute biliary pancreatitis and are discharged for an interval cholecystectomy; during the waiting time such patients often develop new episodes of abdominal pain. Recurrent pancreatitis is diagnosed when a patient previously diagnosed with acute pancreatitis develops new abdominal pain after apparent resolution of the first one.[6,7] Most studies on recurrent pancreatitis focus on diagnosis, treatment, etiology and prognosis of patients from the point of diagnosis at admission. Few studies have attempted to examine backwards into the previous abdominal pain episodes in patients admitted for acute pancreatitis. This issue also raises the question whether the episodes of pain experienced by a patient prior to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis can actually be those of recurrent pancreatitis? If this be true, a more accurate diagnosis of recurrent pancreatitis would gain clinical relevance as an important prognostic indicator because recurrent attacks have different clinical outcomes than single pancreatic episodes.[2,8] Our study aimed to analyze factors associated with abdominal pain episodes occurring prior to a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and to elucidate the possible pancreatic origin of these episodes.

Methods

This study was conducted from October 2009 to February 2011. We collected data on biliary pancreatitis patients admitted at our institution. Inclusion criteria included: female patients of biliary pancreatitis admitted at our institution; and the patient’s age and severity of pancreatitis did not affect the individual’s inclusion into the study. Diagnosis was based on clinical criteria and serum and/or urinary amylase test (2.5 times over normal) To confirm biliary pancreatitis and rule out other types of pancreatitis, the following criteria were used:9 1) patients with signs of biliary sediment (macrolithiasis, microlithiasis and/or biliary sludge) confirmed on ultrasound; 2) patients without history of abundant alcohol ingestion 72 hours before the initial episode; and 3) patients who did not have serum cholesterol over 250 mg/dl. Data was obtained by direct patient interrogation and from patient medical records. Transabdominal ultrasound (TUS)(General Electric logic 7 with 3.5 MHz transductor) was performed in all patients at admission. In all our patients biliary sediment was found, either as sludge or in the form of micro/macrolithiasis. No confirmatory endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was necessary.[10] The critera for diagnosing biliary sludge included the presence of low-amplitude echogenicity on ultrasound; microlithiasis was considered when stones less than 3 mm were visualized; and larger stones were reported as macrolithiasis.[11,12] Gallbladder wall thickness, common bile duct dilation and ultrasonographic alterations of the pancreas were also analyzed. A wall thinner than 3 mm and a common bile duct smaller than 4 mm in patients younger than 50 years was considered normal. Beyond this age an increase of 1 mm per 10 years was expected.[13] Pancreatic alterations included increased size, edematous appearance and/or presence of peripancreatic fluid.[14] Prognosis was evaluated with Ranson’s criteria, both at admission and at 48 hours.[15] The criteria to evaluate a previous abdominal pain episode in a hospitalized patient was the presence of an upper abdominal pain that required medication for relief and occurred at least one month before the actual episode which clinched the diagnosis.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize overall information. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviation (SD). Binomial tests were used to compare various clinical characteristics in presence of previous abdominal pain episodes. Data were analyzed using SPSS v14.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

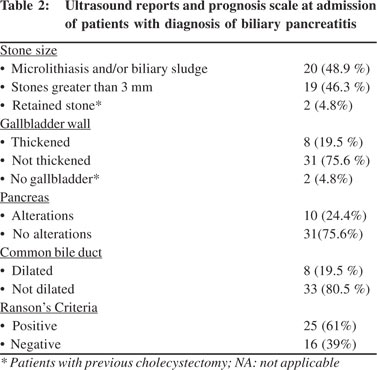

Data for this study was collected from 48 hospitalized women with biliary pancreatitis. Their mean age was 31.6 years (SD+13.9), and mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.6 (SD+4.5). Four (8.3%) patients had diabetes mellitus and seven (14.6%) had hypertension. Eight (16.6%) patients had had at least one previous abdominal surgery. Forty one (85.4%) patients gave at least one history of previous abdominal pain episode. The remaining 7 (14.6%) experienced such pain only for the first time at diagnosis and were not included in the study analysis. Clinical features of the 41 patients with at least one previous abdominal pain episode are summarized in Table 1. Thirtyseven (90.2%) patients reported that for at least one episode they took antacid treatment (proton pump inhibitors or H2 receptor antagonists) either by medical prescription or by self medication with a suspicion of “gastritis”. Of these 41 patients, 39 (95.1%) presented with biliary sediment (sludge and/or micro/ macrolithiasis) during ultrasound evaluation. Two patients had had a previous cholecystectomy and in these cases the cause of the pancreatitis was a retained stone. The rest of the ultrasonographic findings and Ranson´s criteria are reported in Table 2.

Discussion

This study analyzed 41 female patients who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of biliary pancreatitis and had had at least one previous abdominal pain episode. Abdominal pain can be caused by many etiologies but an adequate anamnesis can usefully reduce this list. The most common causes of upper abdominal pain are pancreato-biliary and peptic ulcer disease.[16] A distinctive feature of pancreatic abdominal pain is the lack of spontaneous relief. While some pain may be reduced by leaning forward but most episodes need medications.[17] Accordingly we based our evaluation of previous abdominal pain episodes on their upper abdominal location and lack of spontaneous relief. Sajith et al[18] suggest a two-month asymptomatic period between the pancreatic episodes, to consider it as recurrent pancreatitis. Zhang et al[19] defined recurrent pancreatitis as a new episode after resolution of the first one. They did not mention a minimum duration of the asymptomatic window between the episodes. No consensus has been established on this issue. In our study at least one asymptomatic month between the diagnosis of biliary pancreatitis and a prior episode was needed to consider it a previous abdominal pain episode. In order to eliminate variables pertaining to pancreatitis men were not included in this study and the analysis of biliary pancreatitis was carried out in women since gallbladder stones are much more frequent in them. In Latin women the mean age of presentation of biliary pancreatitis is around 36 years[20,21] which is similar to the mean age of 31.6 years of our patients. Our patients had a mean BMI of 27.5 which is also similar to previous reports.[22] Abdominal pain is the main symptom of biliary pancreatitis which prompts most patients to seek medical attention. However, a proportion of these cases are not diagnosed and/or treated correctly, and they suffer multiple abdominal pain episodes punctuated by asymptomatic periods eventually setting in recurrent pancreatitis. This scenario was shown in a study by Neri et al[23] where they found nearly 30% of biliary pancreatitis attacks at diagnosis were actually a recurrent episode. They attributed recurrent biliary pancreatitis to temporal obstruction of the sphincter of Oddi by biliary waste (microlithiasis, biliary sludge). The objective of this article, as previously mentioned, was to find factors that are associated with previous abdominal pain episodes in women with biliary pancreatitis, to clarify if these previous episode are caused by pancreatic inflammation. Accordingly we analyzed data on 41 women who had had previous pain episodes. The remaining seven patients were excluded from the analysis since it was their first abdominal pain episode. Contrary to what Neri et al reported, we found only 14.6% patients presented with a first abdominal pain episode at diagnosis, while most others (85.4%) had suffered prior episodes. It is possible that the recurrent abdominal pain episodes are caused by the passage of biliary waste to the duodenum, as suggested by Neri et al. The fact that we found a larger number of patients with recurrent pain episodes may have to do with their education and lowmedium socioeconomic class, which may influence their delay in seeking medical attention.[24,25] A large proportion of our patients (90.2%) reported treating at least one episode of previous abdominal pain with H2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors, since it was thought to be a “gastritis” episode.[26] Probably, this situation reflects the lack of control of some drugs in our country, the popularity of these drugs in our general population, and in the cases where they were prescribed, the general lack of skills shown by the physician. Nevertheless, we cannot be certain that the 41 cases with previous abdominal pain episodes were due to acute pancreatitis, acid peptic disease or some other cause, but all of these patients were eventually diagnosed with biliary pancreatitis. In view of our hypothesis that these previous abdominal pain episodes are a consequence of pancreatic inflammation, it is important to note that in the majority (75.6%) of our cases such episodes presented within the past year (p=0.001). This is similar to the study of McCullough et al[27] where they reported recurrent episodes shortly after the initial episode resolved. We believe that most previous abdominal pain episodes in our patients were actually episodes of acute pancreatitis which resolved spontaneously, proving the pathophysiology proposed by Neri et al. In our study, 63% of patients experienced epigastric pain and 56% experineced during at least one previous abdominal pain episode clinical manifestations suggestive of biliary obstruction, such as jaundice, acholia and/or dark urine. Such manifestations considerably increase the suspicion of a pancreato-biliary pathology rather than acid peptic disease.[28] In addition, literature indicates that around 90% of biliary pancreatitis patients have microlithiasis and/or biliary sludge.[29] We found that 48.8% of our patients had such findings at admission.

Simce stone formation is not a rapid event and takes years to manifest[30] it is possible that microlithiasis and/or biliary sludge is often present during the initial abdominal pain episodes further strengthening our hypothesis that previous abdominal pain episodes are more often than not pancreatic in origin. Table 1shows other characteristics associated with previous abdominal pain episodes that increase our suspicion of underlying pancreatic alterations. Based on the evidence presented above we propose that most previous abdominal pain episodes are related to a underlying pancreatic inflammation. A decrease in the indiscriminate use of H2 receptor antagonist/proton pump inhibitors and better diagnostic strategies are needed for abdominal pain episodes, mainly at the first level of medical care. If biliary pancreatitis is correctly identification during the first abdominal pain attack, it might be possible to decrease the complications and treatment cost associated with this disease. We believe more comprehensive well designed studies examining previous abdominal pain episodes are needed to validate and explain these clinical phenomena.

References

Discussion

This study analyzed 41 female patients who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of biliary pancreatitis and had had at least one previous abdominal pain episode. Abdominal pain can be caused by many etiologies but an adequate anamnesis can usefully reduce this list. The most common causes of upper abdominal pain are pancreato-biliary and peptic ulcer disease.[16] A distinctive feature of pancreatic abdominal pain is the lack of spontaneous relief. While some pain may be reduced by leaning forward but most episodes need medications.[17] Accordingly we based our evaluation of previous abdominal pain episodes on their upper abdominal location and lack of spontaneous relief. Sajith et al[18] suggest a two-month asymptomatic period between the pancreatic episodes, to consider it as recurrent pancreatitis. Zhang et al[19] defined recurrent pancreatitis as a new episode after resolution of the first one. They did not mention a minimum duration of the asymptomatic window between the episodes. No consensus has been established on this issue. In our study at least one asymptomatic month between the diagnosis of biliary pancreatitis and a prior episode was needed to consider it a previous abdominal pain episode. In order to eliminate variables pertaining to pancreatitis men were not included in this study and the analysis of biliary pancreatitis was carried out in women since gallbladder stones are much more frequent in them. In Latin women the mean age of presentation of biliary pancreatitis is around 36 years[20,21] which is similar to the mean age of 31.6 years of our patients. Our patients had a mean BMI of 27.5 which is also similar to previous reports.[22] Abdominal pain is the main symptom of biliary pancreatitis which prompts most patients to seek medical attention. However, a proportion of these cases are not diagnosed and/or treated correctly, and they suffer multiple abdominal pain episodes punctuated by asymptomatic periods eventually setting in recurrent pancreatitis. This scenario was shown in a study by Neri et al[23] where they found nearly 30% of biliary pancreatitis attacks at diagnosis were actually a recurrent episode. They attributed recurrent biliary pancreatitis to temporal obstruction of the sphincter of Oddi by biliary waste (microlithiasis, biliary sludge). The objective of this article, as previously mentioned, was to find factors that are associated with previous abdominal pain episodes in women with biliary pancreatitis, to clarify if these previous episode are caused by pancreatic inflammation. Accordingly we analyzed data on 41 women who had had previous pain episodes. The remaining seven patients were excluded from the analysis since it was their first abdominal pain episode. Contrary to what Neri et al reported, we found only 14.6% patients presented with a first abdominal pain episode at diagnosis, while most others (85.4%) had suffered prior episodes. It is possible that the recurrent abdominal pain episodes are caused by the passage of biliary waste to the duodenum, as suggested by Neri et al. The fact that we found a larger number of patients with recurrent pain episodes may have to do with their education and lowmedium socioeconomic class, which may influence their delay in seeking medical attention.[24,25] A large proportion of our patients (90.2%) reported treating at least one episode of previous abdominal pain with H2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors, since it was thought to be a “gastritis” episode.[26] Probably, this situation reflects the lack of control of some drugs in our country, the popularity of these drugs in our general population, and in the cases where they were prescribed, the general lack of skills shown by the physician. Nevertheless, we cannot be certain that the 41 cases with previous abdominal pain episodes were due to acute pancreatitis, acid peptic disease or some other cause, but all of these patients were eventually diagnosed with biliary pancreatitis. In view of our hypothesis that these previous abdominal pain episodes are a consequence of pancreatic inflammation, it is important to note that in the majority (75.6%) of our cases such episodes presented within the past year (p=0.001). This is similar to the study of McCullough et al[27] where they reported recurrent episodes shortly after the initial episode resolved. We believe that most previous abdominal pain episodes in our patients were actually episodes of acute pancreatitis which resolved spontaneously, proving the pathophysiology proposed by Neri et al. In our study, 63% of patients experienced epigastric pain and 56% experineced during at least one previous abdominal pain episode clinical manifestations suggestive of biliary obstruction, such as jaundice, acholia and/or dark urine. Such manifestations considerably increase the suspicion of a pancreato-biliary pathology rather than acid peptic disease.[28] In addition, literature indicates that around 90% of biliary pancreatitis patients have microlithiasis and/or biliary sludge.[29] We found that 48.8% of our patients had such findings at admission.

Simce stone formation is not a rapid event and takes years to manifest[30] it is possible that microlithiasis and/or biliary sludge is often present during the initial abdominal pain episodes further strengthening our hypothesis that previous abdominal pain episodes are more often than not pancreatic in origin. Table 1shows other characteristics associated with previous abdominal pain episodes that increase our suspicion of underlying pancreatic alterations. Based on the evidence presented above we propose that most previous abdominal pain episodes are related to a underlying pancreatic inflammation. A decrease in the indiscriminate use of H2 receptor antagonist/proton pump inhibitors and better diagnostic strategies are needed for abdominal pain episodes, mainly at the first level of medical care. If biliary pancreatitis is correctly identification during the first abdominal pain attack, it might be possible to decrease the complications and treatment cost associated with this disease. We believe more comprehensive well designed studies examining previous abdominal pain episodes are needed to validate and explain these clinical phenomena.

References

- Wang GJ, Gao CF, Wei D, Wang C, Ding SQ. Acute pancreatitis: etiology and common pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1427–30.

- Yaday D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323–30.

- Smotkin J, Tenner S. Laboratory diagnostic tests in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:459–62.

- Gocmen E, Klc YA, Yoldas O, Ertan T, Karaköse N, Koç M, et al. Comparison and validation of scoring systems in a cohort of patients treated for biliary acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2007;34:66–9.

- Kasimu H, Jakai T, Qilong C, Jielile J. A brief evaluation for preestimating the severity of gallstone pancreatitis. JOP. 2009;10:147–51.

- Wehrmann T. Long-term results (> 10 years) of endoscopic therapy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in patients with acute recurrent pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2011;43:202–7.

- Coyle WJ, Pineau BC, Tarnasky PR, Knapple WL, Aabakken L, Hoffman BJ, et al. Evaluation of unexplained acute and acute recurrent pancreatitis using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, sphincter of Oddi manometry, and endoscopic ultrasound. Endoscopy. 2002;34:617–23.

- Gullo L, Migliori M, Pezzili R, Olah A, Farkas G, Levy P, et al. An update on recurrent acute pancreatitis: data from five European countries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1959–62.

- Sánchez-Lozada R, Acosta-Rosero AV, Chapa-Azuela O, Hurtado- López LM. Etiology on determining the severity of acute pancreatitis. Gac Med Mex. 2003;139:27–31.

- Mibagheri SA, Mohamadnejad M, Nasiri J, Vahid AA, Ghadimi R, Malekzadeh R. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of biliary microlithiasis in patients with normal transabdominal ultrasonography. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:961–4.

- Saraswat VA, Sharma BC, Agarwal DK, Kumar R, Negi TS, Tandon RK. Biliary microlithiasis in patients with idiopathic acute pancreatitis and unexplained biliary pain: response to therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1206–11.

- Jüngst C, Kullak-Ublick GA, Jüngst D. Gallstone disease: Microlithiasis and sludge. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1053–62.

- Bachar GN, Cohen M, Belenky A, Atar E, Gideon S. Effect of aging on the adult extrahepatic bile duct: a sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:879–82.

- Arger PH, Mulhern CB, Bonavita JA, Stauffer DM, Hale J. An analysis of pancreatic sonography in suspected pancreatic disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1979;7:91–7.

- Osvaldt AB, Viero P, Borges da Costa MS, Wendt LR, Bersh VP, Rohde L. Evaluation of Ranson, Glasgow, APACHE-II, and APACHE-O criteria to predict severity in acute biliary pancreatitis. Int Surg. 2001;86:158–61.

- Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison´s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York: MacGraw Hill; 2011.

- Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Matthews JB, et al, eds. Schwartz´s principles of surgery, 9th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2009.

- Sajith KG, Chacko A, Dutta AK. Recurrent acute pancreatitis: clinical profile and an approach to diagnosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3610–6.

- Zhang W, Shan HC, Gu Y. Recurrent acute pancreatitis and its relative factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3002–4.

- Mendez-Sanchez N, Chavez-Tapia NC, Uribe M. Gallbladder disease and obesity. Gac Med Mex. 2004;140:S59–66.

- Sánchez-Lozada R, Camacho-Hernández MI, Vega-Chavaje RG. Acute pancreatitis: five year experience at the Hospital General de Mexico. Gac Med Mex.2005;141:123–7.

- Stimac D, Krznaric I, Radic M, Zuvic-Butorac M. Outcome of the biliary acute pancreatitis is not associated with body mass index. Pancreas. 2007;34:165–6.

- Neri V, Ambrosi A, Fersini A, Tartaglia N. Therapeutic approach and prevention in recurrent acute biliary pancreatitis. Ann Ital Chir. 2010;81:177–81.

- Kahan E, Giveon SM, Zalevsky S, Imber-Shachar Z, Kitai E. Behavior of patients with flu-like symptoms: consultation with physician versus self-treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 2000;2:421–5.

- Berkanovic E, Telesky C. Social networks, beliefs, and the decision to seek medical care: an analysis of congruent and incongruent patterns. Med Care.1982;20:1018–26.

- Flasar MH, Goldberg E. Acute abdominal pain. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:481–503.

- McCullough LK, Sutherland FR, Preshaw R, Kim S. Gallstone pancreatitis: does discharge and readmission for cholecystectomy affect outcome? HPB (Oxford). 2003;5:96–9.

- Kimura Y, Arata S, Takada T, Hirata K, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, et al. Gallstone-induced acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:60–9.

- Chebli JM, Ferrari Júnior AP, Silva MR, Borges DR, Atallah AN, das Neves MM. Biliary microcrystals in idiopathic acute pancreatitis: clue for occult underlying biliary etiology. Arq Gastroenterol. 2000;37:93–101.

- Mok HY, Druffel ER, Rampone WM. Chronology of cholelithiasis. Dating gallstones from atmospheric radiocarbon produced by nuclear bomb explosions. N Engl J Med.1986;314:1075–7.

|

|

|

|

|

|