|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Surgical Gastroenterology |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

distal pancreatectomy, pancreatic fistula, intra-abdominal abscess, suture method, complications |

|

|

Rachel M Gomes, couponrxsms.com discountNilesh Doctor

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology,

Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre,

Mumbai, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Rachel M. Gomes

Email: dr.gomes@rediffmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.50

Abstract

Background: Distal pancreatectomy (DP) has a high post-operative morbidity predominantly due to pancreatic fistula though the mortality is very low. Data on distal pancreatectomy was reviewed to analyse the risk factors that contribute to this morbidity.

Methods: Thirty three patients underwent distal pancreatectomy with sutured closure of the remnant, over a 5-year period between May 2006 and April 2011. Pancreatic fistula (PF) was defined according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula definition. Patient and surgical risk factors were subdivided as those reflecting a poorer pre-morbid status, those associated with increased complexity of surgery and those related to pancreas gland and were analyzed for incidence of pancreatic fistula.

Results: Indications for DP included 16 (51.5%) pancreatic tumours, 13 (39.4%) chronic pancreatitis and 3 (9.1%) trauma. Spleen was preserved in 12 patients (36.4 %).There was no mortality while the morbidity rate was 45.5% (n=15). Incidence of pancreatic fistula was 30.3% (n=10); eight were grade A (80%) and two were grade C (20%). Incidence of clinically significant pancreatic fistulae was 6.1%. PF was significantly more common if the pancreatic duct was not identified (p=0.024) was significantly less with extensive peri-pancreatic adhesions (p=0.036).

Conclusions: Identification and ligation of main pancreatic duct can help reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistulae. The identification of patients at high risk of developing a PF helps to implement prevention strategies.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|535 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Distal pancreatectomy (DP) continues to remain a procedure with high morbidity though advances in operative technique and peri-operative care of patients have resulted in low mortality.[1-3] Pancreatic fistula (PF) is the most frequent complication occurring in 11 to 31% cases.[1-9] Factors predisposing to morbidity have been studied but poorly characterized. Factors described are method of closure of the pancreatic remnant, splenectomy, high BMI, malnutrition, primary disease, texture, degree of fibrosis etc.[1-9] Identification of patients at high risk of developing a PF allows surgeons to identify and implement prevention strategies to select patients with potential risk factors who will benefit the most.[9] The aim of this study was to classify and analyse risk factors predictive of post-operative pancreatic fistulae in patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy with sutured closure of the pancreatic remnant and to propose simple measures to reduce their incidence.

Methods

Data collection

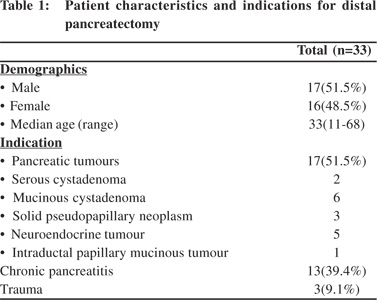

The present analysis included a retrospective review of inpatient data collected prospectively for a total of 33 patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy over a 5-year period between May 2006 and April 2011. Information regarding age, sex, preoperative evaluation, indication for distal pancreatectomy, concomitant splenectomy or other additional procedures, texture of pancreatic parenchyma (graded as soft vs. firm by the surgeon), location of pancreatic transection (neck vs. body ), identification and closure of the main pancreatic duct, operative time, blood loss, peri-operative transfusion and postoperative outcome, was gathered. There were 17 males and 16 females with a median age of 33 years (range 11 to 68 years).The indications for surgery included 16 patients with pancreatic tumours, 13 patients with chronic pancreatitis and 3 with trauma. Twenty one patients underwent distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy and twelve patients underwent spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy. The patient demographics and indications for surgery are summarized in Table 1.

Standard treatment protocols

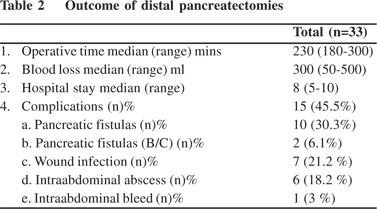

All patients underwent contrast-enhanced abdominal computed patients (30.3%) developed pancreatic fistulae. Eight fistulae (80%) were Grade A and two, Grade C (20%). Two patients (6.1%) developed clinically significant pancreatic fistulae (Grade B/C). Wound infection occurred in seven patients (21.2%), intraabdominal abscess in six patients (18.2%) and intra-abdominal haemorrhage in one (3%). None of patients required a reoperation. The median operative time was 230 min (range: 180-300 min). The median amount of blood loss was 300 ml (50- 500 ml). The median length of post-operative hospital stay was 8 days (range: 5-10 days). The post-operative results are showed in Table 2.

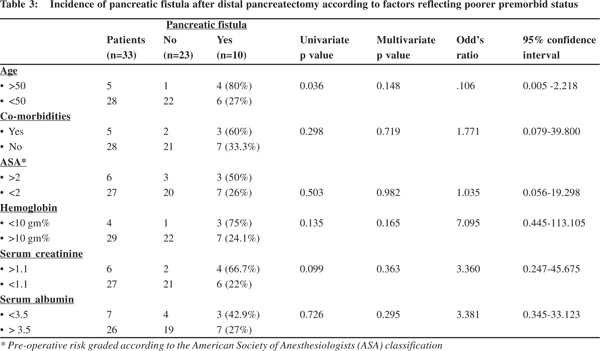

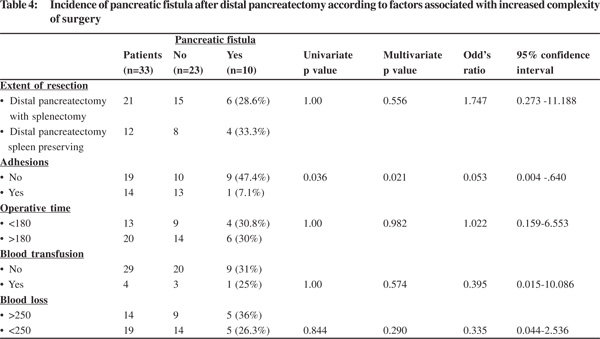

Among factors reflecting poorer pre-morbid status, pancreatic fistula was significantly more common in patients aged >50 years occurring in 4 of 5 (80%) of these patients compared to 6 of 22 (27%) patients <50 years (p=0.036). Other factors analysed included presence of co-morbidities, ASA grade >2, Hb <10 gm%, serum creatinine >1.1 and serum albumin <3.5 gm, which showed higher number of fistulae but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3).Among factors associated with increased complexity of surgery pancreatic fistula was significantly less common in patients with extensive peri-pancreatic adhesions occurring in 1 of 14 (7.1%) patients compared to 9 of 19 (47.4%) of these patients with no adhesions (p=0.036). Other factors analysed included, extent of resection (concomitant splenectomy or not), operation time >3 hours, blood loss >250 cc and blood transfusions which did not show any statistically significant differences on analysis (Table 4).

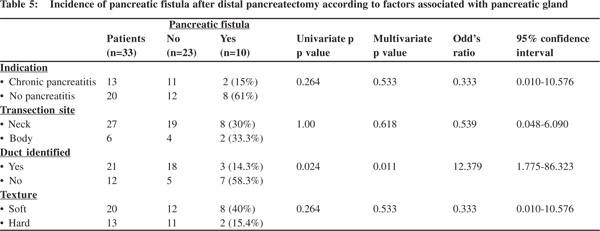

Among factors associated with the pancreatic gland, patients in whom the pancreatic duct was not identified had a significantly higher fistula rate occurring in 7 of 12 (58.3%) of these patients compared to 3 of 21 (14.2%) patients with pancreatic duct identified and ligated (p=0.024). Pancreatic fistula was commoner in those operated for tumours and trauma compared to those with chronic pancreatitis, in those with transection at body (larger remnant volume) compared to neck and in those with a soft gland texture but differences were not statistically significant.

Standard treatment protocols

All patients underwent contrast-enhanced abdominal computed patients (30.3%) developed pancreatic fistulae. Eight fistulae (80%) were Grade A and two, Grade C (20%). Two patients (6.1%) developed clinically significant pancreatic fistulae (Grade B/C). Wound infection occurred in seven patients (21.2%), intraabdominal abscess in six patients (18.2%) and intra-abdominal haemorrhage in one (3%). None of patients required a reoperation. The median operative time was 230 min (range: 180-300 min). The median amount of blood loss was 300 ml (50- 500 ml). The median length of post-operative hospital stay was 8 days (range: 5-10 days). The post-operative results are showed in Table 2.

Among factors reflecting poorer pre-morbid status, pancreatic fistula was significantly more common in patients aged >50 years occurring in 4 of 5 (80%) of these patients compared to 6 of 22 (27%) patients <50 years (p=0.036). Other factors analysed included presence of co-morbidities, ASA grade >2, Hb <10 gm%, serum creatinine >1.1 and serum albumin <3.5 gm, which showed higher number of fistulae but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3).Among factors associated with increased complexity of surgery pancreatic fistula was significantly less common in patients with extensive peri-pancreatic adhesions occurring in 1 of 14 (7.1%) patients compared to 9 of 19 (47.4%) of these patients with no adhesions (p=0.036). Other factors analysed included, extent of resection (concomitant splenectomy or not), operation time >3 hours, blood loss >250 cc and blood transfusions which did not show any statistically significant differences on analysis (Table 4).

Among factors associated with the pancreatic gland, patients in whom the pancreatic duct was not identified had a significantly higher fistula rate occurring in 7 of 12 (58.3%) of these patients compared to 3 of 21 (14.2%) patients with pancreatic duct identified and ligated (p=0.024). Pancreatic fistula was commoner in those operated for tumours and trauma compared to those with chronic pancreatitis, in those with transection at body (larger remnant volume) compared to neck and in those with a soft gland texture but differences were not statistically significant.

Multivariate analysis pertaining to pancreatic fistulae confirmed pancreatic duct identification with ligation (p=0.011) and adhesions (p=0.021) as independent risk factors. Age was not found to be statistically significant on multivariate analysis (p=0.148) (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis pertaining to pancreatic fistulae confirmed pancreatic duct identification with ligation (p=0.011) and adhesions (p=0.021) as independent risk factors. Age was not found to be statistically significant on multivariate analysis (p=0.148) (Table 5).

Discussion

Incidence of post-operative PF is highly variable in literature ranging from nil to up to 64% and this has been attributed to the variability of definitions used.[10] The standardization of the definition of a PF by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) has allowed for better comparisons but has had no impact on incidence with high morbidity and PF rates continuing over time.[11] Many authors have however further refined the ISGPF definition to include only clinically significant fistulas in their studies resulting in only grade B and C PFs being reported.[6,8] This has lead to a more meaningful analysis of risk factors influencing PF. Our series of distal pancreatectomy had a very low clinically significant pancreatic fistula rate of 6.1%.

Discussion

Incidence of post-operative PF is highly variable in literature ranging from nil to up to 64% and this has been attributed to the variability of definitions used.[10] The standardization of the definition of a PF by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) has allowed for better comparisons but has had no impact on incidence with high morbidity and PF rates continuing over time.[11] Many authors have however further refined the ISGPF definition to include only clinically significant fistulas in their studies resulting in only grade B and C PFs being reported.[6,8] This has lead to a more meaningful analysis of risk factors influencing PF. Our series of distal pancreatectomy had a very low clinically significant pancreatic fistula rate of 6.1%.

The risk factors for pancreatic fistulas have been widely studied but still remain poorly characterized. We systematically classified the patient and surgical risk factors into those reflecting a poorer pre-morbid status, those associated with increased complexity of surgery and those related to the pancreas. Perhaps a more complete classification would also take into account factors influencing pancreatic secretions at the sealed transected surface post-operatively including the use of somatostatin analogues and pancreatic stenting to divert the secretions.[12,13] Among pre-operative factors literature has shown that the ASA score, decreased albumin levels, and increased body weight are significantly associated with a PF, including clinically relevant fistulae.[8,9] Rest of the pre-operative risk factors for a PF analysed in our study including lower haemoglobin, higher serum creatinine, age and presence of comorbidities have been analysed in few previous studies, but have not been found to be significantly associated with pancreatic fistulae.[1-9] In this context, the value of pre-operative risk stratification using complex scores like the Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the Enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM) has been found useful for risk assessment for pancreatic resection and other surgical entities.[14,15] But because of difficulty in applying these complex score in clinical practice, they are not widely used. We included a simple analysis of factors reflecting a patient’s poor premorbid status and found an increased incidence of pancreatic fistulae statistically significant only for age >50 years on univariate analysis, however this was not found to be an independent predictor on multivariate analysis. A scientific explanation easy to understand would be that these poorer pre-morbid risk factors may be associated with poorer healing and hence increased incidence of pancreatic fistulae.

Our study identified pancreas related factors to be also associated with a higher incidence of pancreatic fistulae. Sutured closure without ligation of the main pancreatic duct was a significant risk factor and an independent predictor on multivariate analysis. Many studies have identified no specific ligation of the main pancreatic duct as an independent risk factor for pancreatic fistula and demonstrated that identification and ligation of the pancreatic duct as an important factor in reducing the incidence of PF.[7,16] Sandwich fibrin glue, prolamine and ultrasonic dissection have also been shown to reduce pancreatic stump leak and these studies indirectly support mechanical occlusion of ducts especially the main pancreatic duct to reduce overall leakage and manifestation as a PF.[17-19] A recent meta-analysis comparing stapled and hand-sutured closure failed to draw firm conclusions on the optimal method for stump closure and did not reveal significant difference between stapled and hand-sutured closure; although there was a trend favouring stapled closure.[20] All studies in favour of sutured closure of the pancreatic remnant indirectly support the practice of main duct ligation, since all patients who underwent sutured closure had ligation of the main duct, whereas stapled closure did not.

Manual assessment of gland texture has been used since earlier times to differentiate a firm fibrotic gland from a soft fatty non-fibrotic parenchyma. The texture of the pancreatic parenchyma is one of the risk factors for pancreatic fistula and patients with soft pancreatic tissue had higher incidence of pancreatic leakage compared with the presence of firm tissue,[21,22] implying fibrotic pancreas is less likely to pancreatic leakage. Analysis of pathology revealed that chronic pancreatitis is associated with lower PF rate secondary to textural alterations and a congestion of pancreatic duct allowing easy identification and ligation of the main pancreatic duct.[23,24] Studies have identified the site of transection at the body in comparison to the pancreatic neck as an independent risk factor for pancreatic fistula.[7] Recent studies have included volumetry on imaging to show larger size of the remaining gland as a risk factor for pancreatic fistula.[25] The latter leads to a logical observation that larger the volume of the remaining gland, the greater the quantity of actively secreting parenchyma with its effects on the sealed transection area; providing at the same time scientific explanation for previously observed correlation with transection sites.

Among factors increasing operative complexity we have identified extensive peri-pancreatic adhesions as a significant factor for reducing risk of pancreatic fistulae on univariate analysis and an independent predictor on multivariate analysis representing a strange observation with no studies in the literature studying this as a risk factor. Though we have studied this factor, the severity of adhesions is difficult to characterize and very subjective and difficult to compare and will need studies to further confirm its role. Possibly peri-pancreatic adhesions represent repeated attacks of inflammation of the gland associated with increased degree of fibrosis not necessarily reflected as textural alterations. Other factors increasing complexity of surgery reported to increase fistula rates8 were not found significant in our study. We found that increasing complexity was described more in context of multivisceral resections in these studies but our study did not include multivisceral resections and was focussed on increased complexity with the newly adopted method of spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy. The role of splenic preservation after DP remains debatable. Studies subclassifying fistulae into clinically significant fistulae demonstrate that splenectomy is not associated with an increased risk of developing a PF as was found in our series also but is associated with an increased risk of a clinically significant grade B/C PFs suggesting that splenic preservation does not decrease the occurrence of PF but may protect against its progression to infectious complications.[8]

In conclusion, it is important to identify specific risk factors in patients which predispose them to development of pancreatic fistulae. Identification and ligation of the main pancreatic duct can help reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistulae and was the most important predisposing factor that we identified in our study.

References

- Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic resection in the 1990s. Arch Surg. 1995;130:295– 9; discussion 299–300.

- Büchler MW, Wagner M, Schmied BM, Uhl W, Friess H, Z’graggen K. Changes in morbidity after pancreatic resection: toward the end of completion pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1310–4; discussion 1315.

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–37.

- Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229:693–8; discussion 698–700.

- Balcom JH IV, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernandezdel Castillo C. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391–8.

- Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z’graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg.2007;245:573–82.

- Pannegeon V, Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Vullierme MP, Kianmanesh R, Belghiti J. Pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: predictive risk factors and value of conservative treatment. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1071–6; discussion 1076.

- Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, Cheow PC, Ong HS, Chan WH, et al. Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreactomies with emphasis on risk factor, outcome and management of postoperative pancreatic fistula. Arch Surg. 2008;143:956–65.

- Seeliger H, Christians S, Angele MK, Kleespies A, Eichhorn ME, Ischenko I, et al. Risk factors in distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2010;200:311–7.

- Bassi C, Butturini G, Molinari E, Mascetta G, Salvia R, Falconi M, et al. Pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatic resection: The importance of definitions. Dig Surg. 2004;21:54–9.

- Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13.

- Suc B, Msika S, Piccinini M, Fourtanier G, Hay JM, Flamant Y, et al. Octreotide in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications following elective pancreatic resection: a prospective, multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2004;139:288–94; discussion 295.

- Rieder B, Krampulz D, Adolf J, Pfeiffer A. Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy and stenting for preoperative prophylaxis of pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:536–42.

- Pratt W, Joseph S, Callery MP, Vollmer CM Jr. POSSUM accurately predicts morbidity for pancreatic resection. Surgery. 2008;143:8–19.

- Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg. 1991;78:355–60.

- Bilimoria MM, Cormier JN, Mun Y, Lee JE, Evans DB, Pisters PW. Pancreatic leak after left pancreatectomy is reduced following main pancreatic duct ligation.. Br J Surg. 2003;90:190–6.

- Suc B, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Fourtanier G, Hay JM, Holmières F, et al; French Associations for Surgical Research. Temporary fibrin glue occlusion of the main pancreatic duct in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications after pancreatic resection: prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2003;237:57–65.

- Konishi T, Hiraishi M, Kubota K, Bandai Y, Makuuchi M, Idezuki Y. Segmental occlusion of the pancreatic duct with prolamine to prevent fistula formation after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;221:165–70.

- Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Hori Y, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasonic dissector or conventional division in distal pancreatectomy for non-fibrotic pancreas. Br J Surg. 1999;86:608–11.

- Knaebel HP, Diener MK, Wente MN, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of technique for closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:539–46.

- Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:237–41.

- Sheehan MK, Beck K, Creech S, Pickleman J, Aranha GV. Distal pancreatectomy: does the method of closure influence fistula formation? Am Surg. 2002;68:264–67;discussion 267–8.

- Hutchins RR, Hart RS, Pacifico M, Bradley NJ, Williamson RC. Long-term results of distal pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis in 90 patients. Ann Surg. 2002;236:612–8.

- Schoenberg MH, Schlosser W, Rück W, Beger HG. Distal pancreatectomy in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 1999;16:130–6.

- Frozanpor F, Albiin N, Linder S, Segersvärd R, Lundell L, Arnelo U. Impact of pancreatic gland volume on fistula formation after pancreatic tail resection. JOP. 2010;11:439–43.

|

|

|

|

|

|