Blanca E. Alvarez-Fernandez1, Elvia Rodrfguez-Bataz1, Dylan L. Dfaz-Chiguer2, Adrian Marquez-Navarro2, Rosa M. Sanchez-Manzano2, Benjamin Nogueda-Torres2

Unidad Académica de Ciencias Químico Biológicas de la U.A.G.,1

Av. Lázaro Cárdenas, S/N. Ciudad Universitaria,

C.P. 39090, Chilpancingo, Guerrero.

Departamento de Parasitología,2

Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas-IPN,

México DF, 11340

México

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Benjamín Nogueda-Torres

Email: bnogueda@hotmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.20

48uep6bbphidvals|505 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Tapeworms are among the oldest of all human afflictions and they are an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.[1] Although higher vertebrates may be infected by more than 400 species of the genus Hymenolepis, only H. nana and H. diminuta cause disease in humans. Hymenolepiasis has a high prevalence in populations in tropical and subtropical climates characterized by poor hygiene and poverty.[2,3] Of the two forms of infection, H. nana (dwarf tapeworm) is the most common human tapeworm wordwide; it occurs most frequently in children, although adults may also become infected. In Mexico, H. nana is one of the most frequent intestinal helminthiasis,[4-7] and it also occurs frequently in children as in other countries.[8,9] Humans or rodents act as definitive hosts, and arthropods, such as beetles (Tenebrio and Tribolium) or fleas (Ctenocephalides, Xenopsylla, Pulex), act as intermediate hosts.

Case report

Two members of a Mexican family were diagnosed with mixed parasitosis during the course of a study into the prevalence of enteroparasitosis in Chilpancigo, Guerrero. The 38-year-old mother presented with a year long history of anorexia, diarrhea and intestinal cramps. Her 12-year-old son presented with a similar year long history of frequent episodes of abdominal pain and alternating constipation and diarrhea. Despite a good appetite and nutritional intake, the boy failed to gain weight. Over the preceding 5 years, all five members of the family had been administered an annual 400 mg dose of the anti-parasitic medication, albendazole as a prophylactic strategy via the National Health Service. The most recent dose had been taken 3 weeks prior to the present study.

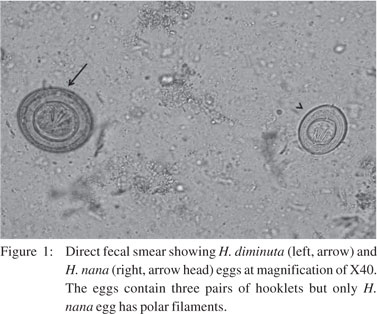

Direct examination of the feces of both patients revealed the presence of two types of eggs. The first and most frequent type was spherical with a thick shell, a 70–80 ?m diameter and six central hooks without polar ûlaments. This was identified as H. diminuta. The second type was spherical to sub-spherical in shape, had a thin, hyaline shell, a 30–45 µm diameter and bipolar filaments. This was identified as H. nana (Figure 1). No proglottids were detected and neither patient reported having observed worm-like structures in their feces. The patients were treated with a 3 day course of nitazoxanide (500 mg/day) via the National Health Service. Weekly evaluation of fecal specimens over a two month period and subsequent evaluations failed to detect the presence of eggs, which indicated that the treatment was successful.

Discussion

Several cases of H. diminuta infection have been reported, and these have mainly involved children.[10-14] As with other soil-transmitted parasitoses, hymenolepiasis is confined to rural areas characterized by poor sanitation. Following the identification of the two cases described in the present report, a search was made for sources of infection in the local environment. Rats and mice were captured and their feces were analyzed. Two of the 10 rats were infected with both Hymenolepis species, and one rat was infected with H. diminuta. The captured mice showed no evidence of infection with these hymenolepids.

Hymenolepiasis due to H. diminuta is often asymptomatic, although clinical manifestations such as anorexia, abdominal pain, pruritis, diarrhea, and eosinophilia may occur as a result of damage to the mucosa (lamina propia) of the intestinal villi. Symptoms similar to those described for infections such as

Taenia saginata have been reported.[15,16,3] Following exposure Figure 1: Direct fecal smear showing H. diminuta (left, arrow) and H. nana (right, arrow head) eggs at magnification of X40. The eggs contain three pairs of hooklets but only H. nana egg has polar filaments. to a primary infection, the host develops a series of specific and nonspecific responses to the adult worms and the intestinal infection is thus considered to be self-limiting.[17] However, the hymenolepiasis may be exacerbated in patients who have an immunosuppressive disease or who are receiving immunosuppressive therapy.[16] Although some of the signs described above are reported in the literature, the physical examination of the two patients did not show these clinical forms of immunosuppressive disease.

Praziquantel is the medication of choice for the treatment of a H. diminuta infection,18 and niclosamide is an effective alternative.[19,20] However, the availability of both medications in rural areas of Mexico is limited. This report describes mixed Hymenolepis species infection in two members of the same family and the role of the rat as a reservoir of both cestodes. This highlights the need to control this harmful pest. The establishment of a precise diagnosis and the reporting of all cases of hymenolepiasis are important factors in improving knowledge of epidemiology, clinical presentation and in developing effective treatment protocols.

References

- Tanowitz HB, Weiss LM, Wittner M. Tapeworms. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2001;3:77–84.

- Melhorn H. Dwarf Tapeworm. In: Melhorn H, editor. Encyclopedia of Parasitology. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2008.

- Roberts L, Janovy JJr. Tapeworms. In: Roberts L, Janovy J, editors. Foundations of Parasitology. 8th ed. Boston: McGraw Hill; 2009.

- Guevara Y, De Haro I, Cabrera M, De la Torre GG, Salazar- Schettino PM. Role of the employment status and education of mothers in the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in Mexican rural schoolchildren. Parasitol Lat. 2003;58:30–4.

- Jiménez-González DE, Márquez-Rodríguez K, Rodríguez JM, Gonzales X, Oxford J, Sánchez R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with intestinal parasites in a rural community of central México. J Parasitol Vect Biol. 2009;1:9–12.

- Quihui L, Valencia ME, Crompton DWT, Phillips S, Hagan P, Morales G, et al. Role of the employment status and education of mothers in the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in Mexican rural schoolchildren. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:225.

- Quihui-Cota L, Valencia ME, Crompton DWT, Phillips S, Hagan P, Diaz-Camacho SP, et al. Prevalence and intensity of intestinal parasitic infections in relation to nutritional status in Mexican schoolchildren. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:653–9.

- Houmsou RS, Amuta EU, Olusi TA. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among primary school children in Makurdi, Benue State- Nigeria. Internet J Infec. Dis. 2010;8:2.

- Sirivichayakul C, Radomyos P, Praevanit R, Pojjaroen-Anant C, Wisetsing P. Hymenolepis nana infection in Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai. 2000;83:1035–8.

- Martínez Peinado C, López Perezagua Mdel M, Arjona Zaragozí FJ, Campillo Gallego Mdel M. Parasitosis in an Ecuadorian girl. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2006;24:207–8.

- Mowlavi GH, Mobedi I, Mamishi S, Rezaeian M, Haghi Ashtiani MT, Kashi M. Hymenolepis diminuta (Rodolphi, 1819) infection in a child from Iran. Iranian J Publ Health. 2008;37:120–2.

- Tena D, Pérez Simón M, Gimeno C, Pérez Pomata MT, Illescas S, Amondarain I, et al. Human infection with Hymenolepis diminuta: case report from Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2375–6.

- Verghese SL, Sudha P, Padmaja P, Jaiswal PW, Kuruvilla T. Hymenolepis diminuta infestation in a child. J Commun Dis. 1998;30:201–03.

- Watwe S, Dardi CK. Hymenolepis diminuta in a child from rural area. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:149–50.

- Craig P, Ito A. Intestinal cestodes. Curr Opin Infec Dis. 2007;20:524–32.

- Raether W, Hänel H. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations and diagnosis of zoonotic cestode infections: an update. Parasitol Res. 2003;91:412–38.

- Andreassen J, Bennet-Jenkins EM, Bryant C. Immunology and biochemistry of Hymenolepis diminuta. Adv Parasitol. 1999;42:223–75.

- The medical letter on drugs and therapeutics. Drugs for parasitic infections. August 2010. http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/PDF_Files/MedLetter/TapewormInfection.pdf.

- Cohen IP. A case report of a Hymenolepis diminuta infection in a child in St James Parish, Jamaica. J La State Med Soc. 1989;141:23–4.

- Tanowitz HB, Weiss LM, Wittner M. Diagnosis and treatment of intestinal helminths. I. Common intestinal cestodes. Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:265–73.

|