48uep6bbphidvals|489

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Gastro esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic disease affecting a significant proportion of the population and often interfering with the quality of life. The aim of medical therapy for GERD is to provide long term relief of symptoms, improve quality of life, enhance and sustain healing of erosive esophagitis and prevent complications such as esophageal stricture, Barrett's esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma. Maximizing therapy for patient with symptomatic GERD therefore becomes a necessity. Thus individuals with chronic GERD with frequent and severe symptoms would require longterm regular use of anti-reflux medications.

Current medical treatment involves medications that suppresses gastric acid secretion e.g. proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and surgery that strengthens the lower esophageal (LES) sphincter pressure and prevents reflux. Both these anti-reflux therapies have been shown to be effective in controlling GERD symptoms. There may be a limited role for modifying life style variables.

The Asian perspective

The clinical course of gastro esophageal reflux (GER) in most Asian patients is benign, majority having non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), and its progression to erosive esophagitis (ERD) is low.[1] Published data from Asia showns a wide range in the prevalence of erosive esophagitis from <1.0% to 20.8%.[1,2] Also GERD related complications are low.[2] Despite these known facts, there has in recent times been a changing trend towards a rising incidence of GERD2 and its complications, coinciding largely with a decline in H. pylori infection.[3,4]

Natural history of GERD

The natural history of GER suggests that there are two possible alternatives for its outcome.[5,6] In the first instance, if GERD is considered as a spectrum of disease progressing from NERD to ERD, Barrett's and adenocarcinoma,[7] then long-term maintenance with acid suppressants is indicated under these circumstances. Regression in grades of esophagitis has been reported following adequate treatment.[5] On the other hand, if GERD is considered as comprising of three discrete phenotypical entities such as NERD, ERD, and Barrett's esophagus,[8] long term maintenance with acid suppressants is not the answer, as the progression from one disease to another is less likely, and even if it were to be so, this would take several decades.[9]

Choice of drug

As per the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, acid suppression is the mainstay of therapy for symptom relief in GERD in both the acute and long-term treatment of the disease.[10] Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the mainstay of treatment which provides most rapid symptom relief and heal esophagitis in the highest proportion of patients. It is recommended for both moderate and severe GERD and its complications.[10] For milder forms of GERD, H2RAs in divided doses are recommended for effective symptomatic relief. It has a relatively rapid onset of action, and is effective in treating episodic heartburn, an effect that is augmented by the coadministration of antacids. Pooled results from clinical trials on H2RA demonstrate a 50 to 75% rate of symptom control and mucosal healing.[11] However it is less effective in patients with moderate to severe erosive disease, with response rates of nearly 80% in grade I to II esophagitis, but only 30 to 50% in grade III to IV disease.[12-14] Overall, H2RAs are less potent than PPIs in management of moderate to severe GERD.

Head-to-head trials comparing the many available PPI formulations have demonstrated similar efficacy in the treatment of GERD. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of PPIs in the treatment of erosive esophagitis reported no significant difference among omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole in control of symptoms or rates of mucosal healing,[15] so also with esomeprazole.[16]

Ideally the drug is given as a single dose, often 30 min before breakfast. Night time acid control is possible with an evening dose. Higher doses of PPI are given in divided doses i.e. a dose in the morning and the second dose before the evening meal. This is especially indicated in patients with noncardiac chest pain, atypical GER symptoms, partial responders, responders but with breakthrough symptoms, Barrett's esophagus and those with abnormal esophageal motility. Not uncommonly, despite the twice a day PPI dose, several patients continue to secrete acid at night (nocturnal acid breakthrough).

H2RAs have a role in inhibiting nocturnal acid secretion. When given either at bedtime or after the evening meal, H2RA often provides effective night time relief, in patients with nonerosive disease or mild erosive esophagitis. Those with moderate to severe esophagitis may require high doses given twice daily.[17] When given as a supplement to PPI therapy, only a small dose of H2RA at bedtime is recommended, well separated in time from the evening dose of PPI. As a class of drugs, H2RAs are associated with a low incidence of adverse effects (<4%). The development of pharmacologic tolerance to H2RAs (tachyphylaxis) has been demonstrated in many studies and may occur after as little as 2 weeks of therapy.[18] However, this has not been shown in clinical trials to affect symptom control, mucosal healing or in maintenance therapy.

Although different PPI formulations have comparable efficacy, individual patients may experience idiosyncratic responses to different PPIs and change to another formulation may be indicated if inadequate acid suppression is documented on pH monitoring.[19] Switching over of PPI has been suggested,[20] but there is no evidence to suggest that different PPIs are associated with different symptom response rates in patients with NERD.21 Although PPIs show some differences in their pharmacokinetics, no evidence supports different responses between reflux patients refractory to PPI therapy. One exception is extensive metabolizers of CYP2C19.

Clinical situations requiring long term acid suppressants

GERD is a lifelong disease. Cessation of therapy results in recrudescence of symptoms and/or erosive esophagitis but long-term spontaneous remission is low. The duration of treatment and consequences of therapy are not known. Currently, long term continuous treatment for GER is indicated for:

a. Symptom relief

Reflux symptoms are better controlled with maintenance-dose PPI therapy than with placebo (44.4% vs. 73.4% had significant symptoms).22 PPI also improves quality of life, reduces nocturnal reflux and increases work productivity compared with placebo.[23]

b. Erosive reflux disease

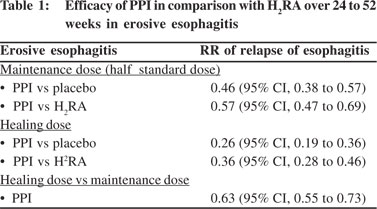

A definite indication for long term maintenance therapy is erosive esophagitis. Recurrence rates of 80% within 12 months and at end of 30 weeks have been reported when treatment is discontinued.[22,24] In another study, 36% of subjects taking PPIs experienced relapse of erosive disease, compared with 75% taking placebo.[25] In presence of such high symptoms and esophagitis relapse rates, long term treatment is justified, i.e. as long as the symptoms last. PPI at standard dose remains the drug of choice for relapses (PPI: 22% vs. H2RA 58% relapse of esophagitis), maintaining healing, controlling symptoms and is superior to placebo (93% vs. 29% at 6 to 12 months).[25,26] Even smaller doses of PPI i.e. half the dose given 12 hourly is better than H2RA (PPI: 40% vs. H2RA: 66% relapse of esophagitis) in maintaining endoscopic remission in 35 to 95% of patients with esophagitis.[22,27] A systematic review compared the efficacy of PPIs with that of H2RAs over 24 to 52 weeks for erosive esophagitis[22] (Table 1).

c. Non-erosive reflux disease

Patients with NERD are as symptomatic as patients with erosive esophagitis and require continuous treatment for control of symptoms,[28] based on the fact that NERD is the common type of esophagitis in the Asian subcontinent. Individuals have normal esophageal motility and low exposure of the esophagus to acid. Hiyama et al[29] recommend PPI in combination with a prokinetic as the first-choice treatment. Metz et al recommend an on-demand empiric trial of acid suppression with PPIs after an initial 2- to 4-week continuous PPI.[30]

However, PPIs are less effective in NERD (though better than H2RA) than in ERD. Low-dose 'on-demand' PPI therapy yields acceptable symptom control in 83–92% of endoscopynegative patients.[27,31] In a single RCT study, benefit was seen for omeprazole 10 mg once daily over placebo (RR: 0.4; 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.53) when given for a long period of time.[22]

d. Extra esophageal reflux syndromes

The approximate prevalence of esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus in extra esophageal reflux syndromes is 12% and 7%, respectively. [32,33] Treatment beyond 8 weeks is often recommended in these patients because at least 40–50% of patients have persistent symptoms after termination of empirical PPI therapy. [34]

In a double-blind placebo-controlled trial addressing the issue of discontinuing PPI therapy in those on chronic PPI therapy, only 21% were PPI free at one year in patients with typical GERD symptoms and in 48% in those with atypical GERD symptoms, indicating the need for long-term use in many patients.[35] Step-down therapy is recommended for relief of symptoms.

e. Refractory gastro esophageal reflux disease (Refractory GERD)

This is also referred to as "gastro esophageal reflux disease (GERD) despite therapy" i.e. the individual continues to experience GERD symptoms while on standard treatment or twice a day dosing of PPIs. Refractory GERD may affect up to 40% of patients on once a day PPI. Evaluation includes checking the compliance and dosage of PPI (including double dosing) before considering investigations. Upper GI endoscopy is the first investigation for refractory GERD with an aim to document the presence or absence of reflux disease and also to exclude gastric pathology.[36]

Refractory GERD with esophagitis: Endoscopy may demonstrate a pill injury or eosinophilic esophagitis. Less common causes are Zollinger–Ellison syndrome or a genotype that confers an altered ability of these patients to metabolize PPIs.

Refractory GERD without esophagitis: Endoscopy is normal in these patients and it is difficult to manage these cases. Further investigations are necessary to confirm presence of reflux (acid or non-acid) by prolonged pH monitoring, impedance testing for non-acid GER, esophageal manometry and gastric function tests. Impedance-pH monitoring is a very sensitive test and helps in detecting persistent acidic reflux. Bilitec test is able to detect bile reflux.[37] Not much is known about management of non-acid reflux. Achalasia and gastroparesis can occasionally manifest with heartburn.

Functional heartburn

Functional heartburn is defined as episodic retrosternal burning in the absence of pathological GER, motility disorders or structural abnormalities.[38] Among untreated patients who have heartburn and normal endoscopy findings, 30–50% have normal 24 h pH test results, thus meeting the criteria for functional heartburn.[39] The results of two impedance studies published in 2006[40,41] indirectly implied that 50–60% of symptomatic patients who are on twice-daily PPIs have no symptom correlation with either acid reflux or non-acid reflux. The functional heartburn group, therefore, accounts for most of the patients with GERD who are refractory to PPI therapy. Visceral hyperalgesia is the main mechanism underlying functional heartburn. These patients require drugs such as tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors which modulate pain.[39]

Duration of medical treatment

GERD can be effectively managed by non-surgical measures; long-term PPIs are considered to be safe and effective. It represents the mainstay of therapy for both NERD and ERD. The induction dose is maintained to prevent relapse and establish remission.[24]

Individuals with GER may experience symptoms intermittently or on almost all days. The duration of therapy is therefore tailored individually. Medical treatment is continued until the patient is relieved of symptoms, often up to 12 weeks (Figure 1).[42] Further continuation of medical treatment with an optimal dose or opting for surgery is considered when recurrence is almost immediate on temporary discontinuation of PPI. Till date, no upper limit duration has been defined.

The prime indication for GERD treatment is to prevent recurrence of symptoms and/or erosive disease, development of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal carcinoma.

Types of medical treatment

Medical therapy for GERD can be divided into short term therapy and long term therapy based on the expected duration of treatment. Long term therapy can be further instituted as a) continuous maintenance therapy and b) discontinuous therapy. The latter discontinuous regime can be either intermittent therapy or 'on-demand' drug therapy as and when required by the patient.[43]

Short term therapy

Short course of treatment is effective in controlling symptoms in GERD patients treated empirically and in endoscopy negative symptomatic GERD patients. The duration of treatment varies from 2 to 8 weeks.[44] For empirical treatment of GERD, PPIs at standard or half dose are superior to standard dose H2RA. Likewise in ENRD, standard dose of PPI is superior to H2RA. Patients with short duration of symptoms may benefit equally with H2RA or PPI.

For symptoms of GER occurring once a week or two to three times a month, short term treatment with 'on-demand' antacids or mucosal protectants accompanied by life style modifications is considered adequate. Effective symptom relief occurs in about one quarter of these patients.[45]

Continuous maintenance therapy

Long-term treatment options in reflux disease include continuous maintenance therapy, mainly for those with erosive reflux disease. Continuous maintenance therapy is daily administration for months or even years to prevent relapse of GER symptoms in patients with severe reflux disease. Intermittent therapy is patient-initiated short courses of therapy with a fixed duration. The patient resumes therapy when the symptoms recur, and continues to take the therapy for 4, 6, or even 8 weeks. In on-demand therapy however, the patients start the therapy on their own and stop the therapy as well on their own. Acid-reducing drugs are taken only when symptomatic. Other forms of continuous treatment are weekend treatment or alternate-day treatment.

For patients with more severe symptoms i.e. 3 or more times a week, or patients with ERD, require long term maintenance treatment for relief of symptoms. Data is available on symptom relief and complications of GERD when patient is on medical treatment for 5 to 10 years.[46,47] These studies have shown that one can achieve symptom control as well as maintain healing of mucosa. Adverse events and side effects are rare. Serum gastrin levels are moderately elevated[47,48] and levels are similar to that following vagotomy. Despite the advantage of symptom relief, long term PPI therapy does not cause regression of Barrett's esophagus nor does it prevent adenocarcinoma.

Discontinuous treatment

Recurrence rates are high with 'on-demand' therapy (42% vs. 19% at 6 months, p<0.001). Tsai et al[49] randomized 622 subjects with non erosive disease to receive either on-demand esomeprazole 20 mg or daily lansoprazole 15 mg. Individuals receiving on-demand therapy were keen on continuing therapy than subjects in the continuous therapy arm (93% vs. 88%) and used much less medication (0.3 vs. 0.8 doses per day).

Intermittent versus 'on-demand' medical therapy

Both intermittent and 'on-demand' treatment regimen are recommended for long term maintenance of acid suppression and in patients with NERD and mild symptoms. On-demand treatment is an established administration schedule for mild/

moderate GERD. It is an effective and cost-reducing strategy for long-term management. The goal of reflux treatment is not necessarily complete absence of symptoms and normalization of minor epithelial lesions, but satisfactory relief of symptoms, healing of major esophageal lesions and prevention of complications. While on-demand and daily treatment models of maintenance therapy show high efficacy, intermittent therapy has been found significantly less effective.[50]

In intermittent dosing, the PPI is taken two or three times a week and in 'on-demand' therapy, the patient takes the PPI continuously for as many days often for 2 weeks followed by 'off PPI' period. Both forms of treatment are taken as an alternative to continuous long term maintenance. A systematic review[51] of five trials had shown that on-demand H2RA therapy was better than placebo. 70–93% of patients were willing to continue treatment. When continuous treatment was compared with 'on-demand' treatment, there was greater satisfaction with 'on-demand' treatment but the difference between the two was small;[52] also the relapse rate was higher in the 'on-demand' group.[53]

Further, systematic review of 17 studies on 'on-demand' therapy with PPIs, concluded that 'on-demand' treatment was effective in the long-term management of patients with NERD or mild esophagitis but not in patients with severe ERD.[54] The therapy was also cost-effective for Asian patients.1 The response to a conventional dose of PPI amongst Asians is generally higher than the western population, partly related to the low parietal cell mass, lower incidence of obesity, low prevalence of hiatus hernia and normal esophageal motility, high frequency of H. pylori infection and severe glandular atrophy of gastric mucosa.1 For these very reasons, surgery may not be indicated in majority of Asian patients with GER.1

In summary, long term / continuous PPI therapy will be required for adequate symptom control in the majority of subjects with GERD symptoms. While many subjects may tolerate dose reduction of their PPI and maintain adequate symptom control, the likelihood of long-term spontaneous remission of disease is low and life style measures are unlikely to be of benefit alone. Beyond recurrence of symptoms and/or erosive disease, the risks associated with cessation of therapy, including the possible development of Barrett's esophagus, are minimal. Data suggest that on-demand dosing or intermittent courses of PPIs are preferred by most patients.

Continuous maintenance therapy versus surgery: differences in quality of life, symptom response and

long term complications

Whether long term PPI really alters the natural history of reflux disease other than to reduce the incidence of peptic stricture is not known. Studies have shown that there is no reduction in the rate of progression to Barrett's esophagus (6%) over a 2 to 20 yr period; or esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with residual GERD. Spechler et al[55] in a follow up study on longterm outcome of acid suppressants and anti-reflux surgery found that at the end of 10 to 12 years, 62% of patients after anti-reflux surgery required PPI on a regular basis while 92% of the medically treated patients continued to be on PPI. One week after discontinuation of medication, GRACI symptom scores (an index used to measure reported symptom type, frequency and severity using a daily diary) were less in the surgical patients compared to those on PPI. Both the groups showed similar grades of esophagitis and similar frequency of peptic stricture. There was no difference in the quality of life scores between the two groups and levels of satisfaction. Ciovica et al[56] made similar observations and found that those after surgery fared marginally better than those on long term PPI.

Lundell et al[57] in a randomized multicenter trial with a 5-year follow-up, compared outcome of anti-reflux surgery with omeprazole in 255 patients with erosive esophagitis (133 patients on continuous omeprazole therapy and 122 having undergone open anti-reflux surgery). The study concluded that anti-reflux surgery was more effective than omeprazole in controlling GERD as measured by the treatment failure rates, but when the dose of omeprazole was adjusted in case of relapse, the two therapeutic strategies reached levels of efficacy that were not statistically different. In one other study by the same author[58] the proportion of patients in whom treatment did not fail during the 7 years was significantly higher in the surgical than in the medical group (66.7 versus 46.7 per cent respectively; p=0.002). More number of patients in the surgical group however complained of symptoms such as dysphagia, inability to belch or vomit and rectal flatulence. Lundell et al[58] in a randomized clinical trial concluded that chronic GERD could be treated effectively by either anti-reflux surgery or PPI (omeprazole) therapy. At the end of 7 years, surgery was found to be more effective in controlling overall disease symptoms, but specific post-fundoplication complaints remained a problem. The dose requirement of omeprazole did not escalate with time.

Pohle et al[24] in a comparative study of short- and long-term medical treatment of GERD, concluded that majority of GERD patients can be effectively managed by non-surgical measures and that long-term use of PPIs is a safe and efficient treatment for GERD.

Is long term treatment with PPI safe?

Long term PPI can result in hypergastrinemia and gastric mucosal atrophy, a potentially pre-cancerous condition.24,[59-61] Comparative trials in which patients were randomly assigned to either anti-reflux surgery or omeprazole treatment have shown that development of atrophy is slightly enhanced after 5 years of PPI therapy,[62] but there is no suggestion that dysplasia or gastric malignancy are more frequent after longterm PPI therapy. Other adverse effects include Clostridium difficile colitis and bacterial gastroenteritis, osteoporosis and vitamin B12 deficiency.[61] However, till date there are no guidelines to consider screening for bone density studies, introduction of calcium supplement or H. pylori screening in these patients on long term PPI.

When should one consider anti-reflux surgery?

Question arises whether patients with GERD need to be treated with PPI for a minimum or maximum period of time before they are referred for anti-reflux surgery. The current indications for anti-reflux surgery include:

- Young patients requiring long term treatment

- Individuals not keen on long duration treatment

- Large volume refluxers, including bile refluxer, presenting as regurgitation

- Refractory GERD

- Patients intolerant to PPI therapy

Patients with GERD need a detailed diagnostic evaluation such as endoscopic biopsy to rule out esophagitis, an esophageal pH–impedance test, esophageal and gastric motility tests and bilitec test before proceeding for an anti-reflux surgery.[34]

Laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery has proven to be a safe and effective treatment for GERD. Several studies have evaluated the short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery with follow-up ranging up to 11 years.[63-65] Typical symptoms of gastrointestinal reflux disease improve in majority of patients after surgery during short and long-term follow-up of more than 5 years. Symptom resolution (90%) is seen over shorter follow-up periods (3 years) than in studies of long-term follow-up (67% of patients at 7-year follow-up).

Improvements have also been demonstrated in patients with dysphagia, Barrett's esophagus, elderly patients, and patients with or without pre-operative esophagitis. Although perioperative and early post-operative dysphagia has been reported as high as 76%; the majority of studies show early mild dysphagia up to 1 year postoperatively to rates less than 20% and long-term rates around 5 to 8%. Regurgitation rates have also been shown to significantly improve following surgery by up to 87 to 97%. Although recurrent or new onset regurgitation has been reported in up to 23% of patients following surgery, the majority of studies reported rates ranging from 0 to 11%. The resumption of acid reducing medications in patients after anti-reflux surgery has been reported to range widely (0 to 62%) at both short and long-term follow-up.[66] Longterm medication use has been reported to range from 5.8 to 62% with most studies reporting rates <20%. One randomized controlled trial, however, reported a 62% incidence of antacid medication resumption after anti-reflux surgery, which constitutes a very high rate compared with the rest of literature.

In a one year follow up of 2406 patients after anti-reflux surgery, Dominitz et al[67] reported dysphagia in 19.4% cases; 6.4% required dilation and 2.3% required a second surgery. The surgical mortality rate was 0.8%. A significant proportion of patients required acid suppressants (H2 receptor antagonists in 23.8%, proton pump inhibitors in 34.3%) and 9.2% required prokinetic agents. At a median follow up of 5 years almost 50% of patients required prescriptions for anti-reflux medications.

Difficult to treat GERD

GERD in obese individuals

GERD appears to be generally more severe in patients with obesity than in lean individuals. Obesity is also associated with an increased risk of esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus, with a substantially increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.[68]

Management issues: The ultimate goal of treating GERD in patients with obesity is weight loss. The latter often results in resolution of symptoms or is rendered controllable with acid suppressants. Although up to 75% of people with obesity lose 10% or more of their body weight on any given attempt, the vast majority regain their weight within 5 years. Aggressive acid suppression therapy with PPI is usually recommended. However, the appropriate use and dosing of PPIs in these patients is not well established. When this fails and symptoms are severe and unremitting with worsening of Barrett's esophagus, or is associated with esophagitis or stricturing, gastric bypass surgery needs to be considered. There is a role for PPI in the post-operative period to reduce ulceration and bleeding in the distal gastric remnant. Also, post surgery, most patients have a pH neutral gastric pouch, but in 5% the pouch is acidic. Reflux of this acid can be overcome with PPI, but in those with neutral pH, sucralfate suspension or an alginate preparation (Gaviscon) is preferred. In symptomatic GERD patients, possibility of bile reflux needs to be considered and bile-acid binder is used both as a diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.

Large hiatus hernia and GER[69]

In a study on 57 healthy subjects with symptomatic GER, Stal et al[70] found that 62% of patients had a hiatus hernia compared to 14% of asymptomatic subjects (p<0.01). Majority had NERD.

Jones et al[71] showed that increase in hiatal hernia size significantly correlated with the total esophageal acid-exposure, acid clearance time and esophagitis severity. Frazzoni et al[72] reported the need for a double dose of lansaprazole in symptomatic GERD patients with a large hiatus hernia. Said et al[73] observed that the presence and size of a hiatus hernia were significantly associated by multivariate analysis, with early recurrence in a group of patients who were followed up for one year after dilation of peptic esophageal stricture. Both these studies concluded that hiatus hernia affects the ability of acid suppressing medication to normalize intra-esophageal pH, probably related to aggravating influence of hiatus hernia on GER. It has been shown that nocturnal acid breakthrough commonly occurs on standard doses of PPIs[74] and it may be that this residual acid refluxes more easily in the presence of a hiatus hernia.

GERD in pediatrics

On-demand therapy with buffering agents, sodium alginate, or H2RA may be used for occasional symptoms. For older children and adolescents with typical symptoms of reflux disease, lifestyle changes when applicable (diet changes, weight loss, smoking avoidance, sleeping position, no late night eating) are necessary along with a 2 to 4-week trial of PPI. If symptoms resolve PPIs may be continued for up to 3 months. Heartburn that persists on PPI therapy or recurs after this therapy is stopped and these children should be investigated. For children with reflux esophagitis or established NERD, PPIs for 3 months will constitute initial therapy. Attempt is made to taper the dose followed by withdrawal of PPI therapy, as majority do not experience recurrence of symptoms.[75]

Recurrence of symptoms and/or esophagitis after repeated trials of PPI withdrawal usually indicate that chronic-relapsing GERD is present, if other causes of esophagitis have been ruled out. At that point, therapeutic options include long-term PPI therapy or anti-reflux surgery.

Pregnancy

Symptomatic GERD during pregnancy can be managed with a step-up algorithm beginning with lifestyle modifications and dietary changes. Antacids or sucralfate are considered the firstline medical therapy. If symptoms persist, H2RAs are recommended. Proton-pump inhibitors are the most effective drug therapy for symptom control and healing of esophagitis. These have not been used as extensively in pregnancy as the H2RAs, nor is their efficacy proven in pregnancy, and the data about total safety are more limited. Today, PPIs in pregnancy are recommended for women with well-defined complicated GERD, not responding to lifestyle changes, antacids and H2RAs. Amongst the PPIs all but omeprazole (category C) are FDA category B drugs.[76]

GERD in elderly

In elderly patients, PPIs have been shown to be more effective than H2RAs for healing reflux esophagitis and for preventing its recurrence when they are given as maintenance therapy. Also, PPIs seem to be safe both in short and long-term therapy of elderly patients with GERD.[77]

There are relatively few studies which have looked into the treatment protocol for the elderly. No comparative studies have been carried out to evaluate which strategy (step-down vs. step-up) is more cost-effective in elderly patients. Another important issue while treating GERD in the elderly is the caution needed to evaluate the concomitant medications, some of which induce GER and others may cause mucosal injury. Studies have shown that PPI once a day is more effective than H2RA in healing esophagitis in the elderly.[78]

There was no difference in healing rates at 8 weeks with any of the PPIs.[79] Maintenance therapy with pantoprazole 20 mg daily for 6 months kept 84% of patients in remission compared to 93% with pantoprazole 40 mg daily, and after 1 year of treatment with lansoprazole, the healing rates were 72% with 15 mg daily and 85% with 30 mg daily. Study on long term treatment has shown that 68% of elderly patients with reflux esophagitis who received initial treatment for acute symptoms required maintenance therapy after 6 months and 46% needed therapy after 3 years. Relapse rates were higher in untreated patients than in those treated with acid inhibitors for up to 3 years.

Other non acid suppressants drugs

Antacids

These provide rapid but temporary relief of heartburn (lasting 30 to 60 minutes) and thus may require frequent dosing. It is recommended for patients with mild GERD or infrequent symptoms. Trials have not shown any healing effect of erosive esophagitis. Alginate preparations (polysaccharide derived from seaweed) have been tried in GERD. These along with an antacid prevent reflux from the acid pocket present adjacent to the gastro-esophageal junction by forming a viscous layer atop the gastric juice. This combination has been demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the relief of GERD symptoms in small studies,[12] when given an hour after a meal. This therapy may be used for the treatment of mild and infrequent heartburn.

Prokinetic agents

Prokinetics though considered a good option, have only modest efficacy in relieving GERD symptoms, and the side effect profile of these agents renders them less useful in clinical practice. However there may be role for these in volume refluxers with severe regurgitation.[19]

Pain modulators

These include tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors[38] and are indicated in functional heartburn.[39]

Future perspectives

Randomized controlled trials of laparoscopic fundoplication versus PPIs with long-term follow-up are needed to ascertain the relative benefits and drawbacks of each approach and whether certain subgroups fare better with one or the other alternative. To minimize patients' exposure to life-long medications, other methods need to be developed to identify patients who need long-term anti-secretory medications. Ondemand therapy regimens are likely to be the future in management of GERD. Further studies are needed to assess the risks associated with prolonged acid suppression for years at a stretch and the consequences of long-term hypergastrinemia.

Recent times have witnessed major advances in the development of newer modalities of GERD treatment.[80] The focus has shifted to 'reflux inhibition' as a potential therapeutic target, i.e. inhibition of transient lower esophageal relaxations (TLESRs), the predominant mechanism of gastro esophageal reflux. This has stimulated the search for better drugs with more effective means of controlling acid secretion i.e. those with a quicker onset of action, a longer half-life, which act faster and for a longer time. These drugs include potassiumcompetitive acid blockers P-CABs e.g. ilaprazole and tenatoprazole. Yet another development amongst the PPIs is the introduction of the immediate-release (IR) formulations such as IR Omeprazole, which rapidly increases intra-gastric pH especially when given at bedtime. This is likely to achieve a better control of nocturnal acidity.[81] CCK2 antagonists are likely to be used as a combination with PPIs rather than a lone anti-secretory compound. The drug will reduce the long-term consequences of hypergastrinemia.

Other new drugs to control GER

The therapeutic efficacy of acid suppression may have reached its maximum. Other mechanisms may have to be targeted to further improve symptom control. Potential drugs interacting with different targets are reflux inhibitors such as GABA(B) receptor agonists and mGluR[5] antagonists. These agents reduce the number of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation thereby reducing both acid and non-acid reflux. GABA(B) agonist baclofen is available for oral therapy; central nervous system side effects may be a limiting factor. These drugs are indicated for NERD or for those with mild erosive GERD. Other emerging drugs to treat GERD include visceral analgesics that would modulate visceral perception or even growth factors to enhance mucosal healing.

As of present, until the efficacy of these new drugs is well established, H2-receptor antagonists (especially soluble or OTC formulations) will become the 'antacids of the third millennium' and will be particularly useful for on-demand symptom relief. PPI would still be the drug of choice to control acid secretion in GERD and other acid-related diseases.

In conclusion, on most occasions, the treatment protocol for chronic GERD needs to be individualized, tailored and monitored.[43] Continuing PPI therapy beyond the stipulated duration is indicated for individuals with persistent symptoms when acid suppressants are withdrawn, atypical symptoms of GERD (non-esophageal symptoms) or those refractory to GERD. Maintenance therapy is titrated to the lowest PPI dose necessary for adequate symptom relief. Very low dose, long term therapy for GERD can be considered extremely safe with an acceptable risk benefit ratio especially if the individual is responsive to anti-secretory treatment.

References

- Wu JC. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: an Asian perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1785–93.

- Goh KL. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Asia: A historical perspective and present challenges. Review. J Gastroenterol Hepaatol. 2011;26:2–10.

- Dent J, El-0Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–7.

- Fock KM, Talley NJ, Fass R, Goh KL, Katelaris P, Hunt R, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:8–22.

- Sontag SJ, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Leya J, Metz A. The longterm natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:398–404.

- Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF; American Gastroenterological Association Institute; Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392–413, 1413.e1–5.

- Pace F, Bianchi Porro G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a typical spectrum disease (a new conceptual framework is not needed). Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:946–9.

- Fass R, Ofman JJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease—should we adopt a new conceptual framework? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1901–9.

- Johnson DA, Fennerty MB. Heartburn severity underestimates erosive esophagitis severity in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:660–4.

- DeVault KR, Castell DO; American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190–200.

- Sontag SJ. The medical management of reflux esophagitis. Role of antacids and acid inhibition. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990;19:683–712.

- Tytgat GN, Nio CY. The medical therapy of reflux oesophagitis. Bailleres Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;1:791–807.

- Sabesin SM, Berlin RG, Humphries TJ, Bradstreet DC, Walton- Bowen KL, Zaidi S. Famotidine relieves symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and heals erosions and ulcerations. Results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. USA Merck Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:2394–400.

- Cloud ML, Offen WW, Robinson M. Nizatidine versus placebo in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1735–42.

- Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A. Healing and relapse rates in gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with the newer protonpump inhibitors lansoprazole, rabeprazole, and pantoprazole compared with omeprazole, ranitidine, and placebo: evidence from randomized clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2001;23:998–1017.

- Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, Vakil NB, Johnson DA, Zuckerman S, et al. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:575–83.

- Barrison AF, Jarboe LA, Weinberg BM, Nimmagadda K, Sullivan LM, Wolfe MM. Patterns of proton pump inhibitor use in clinical practice. Am J Med. 2001;111:469–73.

- Colin-Jones DG. The role and limitations of H2–receptor antagonists in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:9–14.

- Lowe RC. Medical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease.GI Motility online (2006). doi:10.1038/gimo54.

- Fass R, Sifrim D. Management of heartburn not responding to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2009;58:295–309.

- Armstrong D, Talley NJ, Lauritsen K, Moum B, Lind T, Tunturi- Hihnala H, et al. The role of acid suppression in patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease: the effect of treatment with esomeprazole or omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:413–21.

- Donnellan C, Sharma N, Preston C, Moayyedi P. Medical treatments for the maintenance therapy of reflux oesophagitis and endoscopic negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD003245.

- van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD002095.

- Pohle T, Domschke W. Results of short-and long-term medical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Langenbacks Arch Surg. 2000;385:317–23.

- Yaghoobi M, Thabane M, Hunt RH. Response to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy in different grades of erosive esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A490.

- Johnson DA, Benjamin SB, Vakil NB, Goldstein JL, Lamet M, Whipple J, et al. Esomeprazole once daily for 6 months is effective therapy for maintaining healed erosive esophagitis and for controlling gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:27–34.

- Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, Enns R, Fallone CA, Fass R, et al. Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults—update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:15–35.

- Modlin IM, Moss SF. Symptom evaluation in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:558–63.

- Hiyama T, Yoshihara M, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Strategy for treatment of nonerosive reflux disease in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3123–8.

- Metz DC, Inadomi JM, Howden CW, van Zanten SJ, Bytzer P. On-demand therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:642–53.

- Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gasroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:656–64.

- Koufman JA, Belafsky PC, Bach KK, Daniel E, Postma GN. Prevalence of esophagitis in patients with pH-documented laryngopharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1606–9.

- Halum SL, Postma GN, Bates DD, Koufman JA. Incongruence between histologic and endoscopic diagnoses of Barrett's esophagus using transnasal esophagoscopy. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:303–6.

- Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, Hiltz SW, Black E, Modlin IM, American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Affiliations Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee Bottom of Form Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383–91, 1391.e1–5.

- Björnsson E, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M, Mattsson N, Jensen C, Agerforz P, et al. Discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors in patients on long-term therapy: a double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:945–54.

- Richter JE. How to manage refractory GERD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:658–64.

- Karamanolis G, Vanuytsel T, Sifrim D, Bisschops R, Arts J, Caenepeel P, et al. Yield of 24-hour esophageal pH and bilitec monitoring in patients with persisting symptoms on PPI therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2387–93.

- Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Bálint A, Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ, Paterson WG, et al. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1459–65.

- Fass R, Tougas G. Functional heartburn: the stimulus, the pain and the brain. Gut. 2002;51:885–92.

- Zerbib F, Roman S, Ropert A, des Varannes SB, Pouderoux P, Chaput U, et al. Esophageal pH-impedance monitoring and symptom analysis in GERD: a study in patients off and on therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1956–63.

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, Vela M, Zhang X, Sifrim D, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicenter study using ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–1402.

- Tsuzuki T, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Nasu J, Ishioka H, et al. Proton pump inhibitor step-down therapy for GERD: a multi-center study in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1480–7.

- Galmiche JP, Stephenson K. Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: an individualized approach. Dig Dis. 2004;22:148–60.

- van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Lau J, de Wit NJ, Hungin AP, Bonis PA. Short-term treatment of gastro esophageal reflux disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:755–63.

- Koop H. Reflux disease and Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2000;32:101–7.

- Koop H, Arnold R. Long-term maintenance treatment of reflux esophagitis with omeprazole. Prospective study in patients with H2-blocker resistant reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:552–7.

- Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Nelis F, Dent J, Snel P, Mitchell B, Prichard P, et al. Long-term omeprazole treatment in resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease: efficacy, safety, and influence on gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:661–9.

- Koop H, Frank M, Kuly S, Nold R, Eissele R, Rager G, et al. Gastric argyrophil (enterochromaffin-like), gastrin and somatostatin cells after selective proximal vagotomy in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:295–302.

- Tsai HH, Chapman R, Shepherd A, McKeith D, Anderson M, Vearer D, et al; COMMAND Study Group. Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand is more acceptable to patients than continuous lansoprazole 15 mg in the long-term maintenance of endoscopynegative gastro-oesophageal reflux patients: The COMMAND study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:657–65.

- Cibor D, Cieæko-Michalska I, Owczarek D, Szczepanek M. Optimal maintenance therapy in patients with non-erosive reflux disease reporting mild reflux symptoms — a pilot study. Advances in Medical Sciences. 2006;51;336–9.

- Zacny J, Zamakhshary M, Sketris I, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S. Systematic review: the efficacy of intermittent and on-demand therapy with histamine H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors for gastro-esophageal reflux disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1299–312.

- Pace F, Negrini C, Wiklund I, Rossi C, Savarino V; The Italian ONE investigators study group. Quality of life in acute and maintenance treatment of non-erosive and mild erosive gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:349–56.

- Sjöstedt S, Befrits R, Sylvan A, Harthon C, Jörgensen L, Carling L, et al. Daily treatment with esomeprazole is superior to that taken on-demand for maintenance of healed erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:183–91.

- Pace F, Tonini M, Pallotta S, Molteni P, Porro GB. Systematic review: maintenance treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease with proton pump inhibitors taken 'on-demand'. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:195–204.

- Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, Goyal RK, Hirano I, Ramirez F, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2331–81.

- Ciovica R, Gadenstätter M, Klingler A, Lechner W, Riedl O, Schwab GP. Quality of life in GERD patients: medical treatment versus antireflux Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:934–9.

- Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, Pedersen SA, Liedman B, Hatlebakk JG, et al. Continued (5-year) followup of a randomized clinical study comparing antireflux surgery and omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:172–9; discussion 179–81.

- Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, Hatlebakk JG, Wallin L, Malm A, et al. Nordic GORD Study Group. Seven-year followup of a randomized clinical trial comparing proton-pump inhibition with surgical therapy for reflux oesophagitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:198–203.

- Kuipers EJ, Lundell L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Havu N, Festen HP, Liedman B, et al. Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1018–22.

- Graham DY, Genta RM. Long-term proton pump inhibitor use and gastrointestinal cancer. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:543–7.

- Ali T, Roberts DN, Tierney WM. Long-term safety concerns with proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med. 2009;122:896–903.

- Lundell L, Havu N, Miettinen P, et al. No effect of acid suppression therapy over 5 years on gastric glandular atrophy. Results of a randomised study. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A213.

- Morgenthal CB, Lin E, Shane MD, Hunter JG, Smith CD. Who will fail laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication? Preoperative prediction of long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1978–84.

- Cowgill S M, Gillman R, Kraemer E, Al-Saadi S, Villadolid D, Rosemurgy A. Ten-year follow up after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am Surg. 2007;73:748–52; discussion 752–3.

- Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Kohn GP, Reardon PR, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD, the SAGES Guidelines Committee Guidelines for Surgical Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Practice/Clinical Guidelines; 2010.

- Wijnhoven BP, Lally CJ, Kelly JJ, Myers JC, Watson DI. Use of anti-reflux medication after antireflux surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:510–7.

- Dominitz JA, Dire CA, Billingsley KG, Todd-Stenberg JA. Complications and antireflux medication use after antireflux surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:299–305.

- Kaplan LM. Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in obese patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;4:841–3.

- Gordon C, Kang JY, Neild PJ, Maxwell JD. The role of the hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:719–32.

- Stal P, Lindberg G, Ost A, Iwarzon M, Seensalu R. Gastroesophageal reflux in healthy subjects. Significance of endoscopic findings, histology, age, and sex. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:121–8.

- Jones MP, Sloan SS, Jovanovic B, Kahrilas PJ. Impaired egress rather than increased access: an important independent predictor of erosive oesophagitis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:625–31.

- Frazzoni M, De Micheli E, Grisendi A, Savarino V. Hiatal hernia is the key factor determining the lansoprazole dosage required for effective intra-oesophageal acid suppression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:881–6.

- Said A, Brust DJ, Gaumnitz EA, Reichelderfer M. Predictors of early recurrence of benign esophageal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1252–6.

- Peghini PL, Katz PO, Castell DO. Ranitidine controls nocturnal acid breakthrough on omeprazole: a controlled study in normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1335–9.

- Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, Hassall E, Liptak G, Mazur L, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498–547.

- Richter JE. Review Article: The management of heartburn in pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:749–57.

- Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Paris F. Recent advances in the treatment of GERD in the elderly: focus on proton pump inhibitors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:1204–9.

- James OF, Parry-Billings KS. Comparison of omeprazole and histamine H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment of elderly and young patients with reflux esophagitis. Age Ageing. 1994;23:121–6.

- Escourrou J, Deprez P, Saggioro A, Geldof H, Fischer R, Maier C. Maintenance therapy with pantoprazole 20 mg prevents relapse of reflux esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1481–91.

- Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Evolving issues in the management of reflux disease? Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2009;25:342–51.

- Richter JE. Novel medical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease beyond proton-pump inhibitors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:S111–6.