|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Hepatitis C, liver fibrosis, non-invasive tests of liver fibrosis, APRI |

|

|

Rokaya El-Sayed,1 Mona Fahmy,2 Nehal El Koofy,1 Mona El- Raziky,1 Manal El-Hawary,3 Heba Helmy,1 Wafaa El-Akel,4 Ahmad El-Hennawy,5 Hanaa El-Karaksy1

Departments of Pediatrics,1

Tropical Medicine4 and Pathology,5

Cairo University,

Department of Pediatrics,

Research Institute of Ophthalmology,2

Department of Pediatrics,

Fayoum University,3

Cairo, Egypt

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Rokaya Mohamed El-Sayed

Email: rokaya_mohsen@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/

Abstract

Background and aim: We aimed to evaluate the accuracy of readily available laboratory tests (ALT, AST, platelet count, AST to platelet ratio index: APRI) in predicting liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C, in comparison to the predictive accuracy obtained by liver biopsy.

Methods: One hundred and thirteen patients suffering from chronic hepatitis C (CHC) were included in this study. They included 76 children enrolled from the Pediatric Hepatology Unit and 37 adults enrolled from the Hepatology Unit of Tropical Medicine Department, Cairo University, Egypt. Fibrosis results obtained from liver biopsy were assigned a score from 0 to 4 score as per Metavir scoring. Results of serum ALT and AST levels were expressed as ratio of the upper limit of normal (ULN).

Results: Of the pediatric patients, 28 (36.8%) showed no evidence of fibrosis on liver biopsy, 26 (34.2%) showed grade 1 fibrosis, and 22 (29%) had grade 2 fibrosis. Among the adult patients, 12 (32.4%) had grade 2 fibrosis and 25 patients (67.6%) had grades 3 to 4 fibrosis. There was a lack of correlation between the degree of fibrosis and AST levels, AST/ALT ratio, platelet count and APRI. The AUROC curve for predicting significant fibrosis was 0.5 for AST levels, 0.37 for AST/ALT ratio and 0.49 for APRI, in pediatric patients (p >0.05). In adult patients the AUROC curve for predicting significant fibrosis was 0.59 for AST levels, 0.76 for AST/ALT ratio and 0.63 for APRI (p >0.05).

Conclusion: Liver biopsy remains the gold standard to assess the extent of hepatic fibrosis in patients with CHC.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|462 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext More than 170 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide. Patients with chronic HCV may develop decompensated liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. This risk is highest in patients with advanced fibrosis.[1]

The knowledge of stage of liver fibrosis is essential for prognostication and decisions on antiviral treatment.

[2,3] Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients with no or minimal fibrosis at presentation, appear to progress slowly and treatment could possibly be delayed or withheld. On the other hand, patients with significant fibrosis (i.e. septal or bridging fibrosis) progress almost invariably to cirrhosis over a 10-20 years period, thus antiviral treatment is strongly recommended.[4,5]

Liver biopsy is currently the gold standard in assessing liver histology. Although percutaneous liver biopsy is generally a safe procedure, it is expensive and does carry a small risk for complication. Furthermore, liver biopsy is an invasive procedure, prone to sampling error and has the potential for medical complications. Inter- and intra-observer discrepancies of 10 - 20% have been reported in assessing hepatic fibrosis and may lead to erroneous estimation of cirrhosis.

[6,7,8]

Many studies have been undertaken to evaluate the use of readily available laboratory tests to predict significant fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with CHC.

[9,10,11,12] Wai et al concluded from their study that a simple index, the APRI, consisting of 2 readily available laboratory results (AST levels and platelet count), can predict significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in treatment-naïve CHC patients with a high degree of accuracy.[13]

In this study we tried to evaluate the accuracy of the readily available laboratory tests (aminotransferases, platelet count and APRI) in diagnosing liver fibrosis in treatment-naïve CHC patients. Keeping liver biopsy as the gold standard, we also compared the accuracy of correlation between the results of simple lab tests and liver biopsy, with the degree of liver fibrosis predicted by them.

Methods

Patient selection

This study was conducted on 113 pediatric and adult patients suffering from CHC. The diagnosis of CHC was established by the presence of HCV antibody on ELISA and confirmed by the presence of HCV RNA using qualitative polymerase chain reaction assays. Patients with the following conditions were excluded from the study: co-infection with HBV or HIV, coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia to a degree which precludes the safe performance of percutaneous liver biopsy, previously treated HCV infection, biopsies less than 10 mm long and biopsies including less than 5 portal tracts to verify for expanded portal tracts with fewer CD4 cells and more CD8 cells.

[14]

Demographic and clinical information of the patients including, age, sex, laboratory results and liver biopsies reports were obtained from their medical records.

Laboratory results performed within 2 weeks from the date of liver biopsy were used for analysis. If more than one set of laboratory test results were available, the results closest to the time of biopsy were used.

Results of serum aminotransferase (ALT, AST) levels were expressed as ratio of the upper limit of normal (ULN; which was 49 U/L for both ALT and AST). The AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) was calculated according to the following equation devised by Wai et al:

[13]

AST level (/ULN)

APRI = –––––––––––––– X 100

Platelet count (109/L)

Informed written consent was taken from parents of pediatric patients and from adult patients before liver biopsy. The procedure was performed as an outpatient procedure, using a lateral intercostal approach for all patients. We used the percussion technique,

[15] using a 1.6 mm diameter modified Menghini (secure cut) biopsy needle (Hospital Service S.P.A. Via Naro, 91-00040 Pomezia (RM) Italia).

Histopathology slides of all eligible patients were retrieved. All biopsies were reviewed by a single pathologist, who had no knowledge of the clinical characteristics of any of the subjects.

The grade of activity and stage of fibrosis were scored as per published METAVIR criteria,

[16] assigning a score of 0 to 4, where F0 = no fibrosis, F1 = portal fibrosis without septa, F2 = portal fibrosis with few septa, F3 = numerous septa without cirrhosis, and F4 = cirrhosis. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the Cairo University Pediatric Hospital.

Statistical methods

All patient data were tabulated and processed using SPSS v10.0. All patient characteristics were described in numbers and percentage. Spearman correlations were computed between fibrosis score and other laboratory markers (AST, ALT, platelet count and APRI). Receiver operator characteristic curves (ROC) were generated to assess the validity of these markers in diagnosing liver fibrosis reliably in all patients.

Results

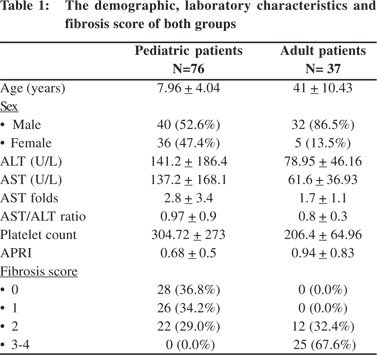

The mean age of the 76 pediatric patients was 7.96 ± 4.04 years; 40 (52.6%) were male and 36 (47.4%) females. Twenty eight (36.8%) patients showed no evidence of fibrosis on liver biopsy (METAVIR F0), 26 (34.2%) patients were graded F1, and 22 (29%) as F2. The adult patient group comprised of 37 patients; including 5 (13.5%) females and 32 (86.5%) males, with mean age of 41 ± 10.43 years. Twelve patients (32.4%) were scored F2 and 25 patients (67.6%) as F3-4. The demographic and laboratory characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1.

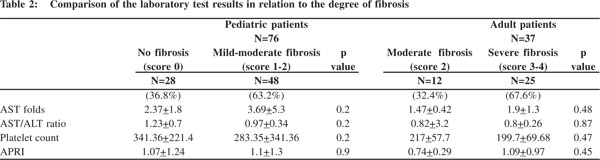

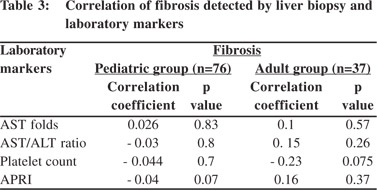

On comparison of laboratory data with the degree of fibrosis, we didn’t find any significant difference between the results for children with and without liver fibrosis or for adults with moderate and severe fibrosis (Table 2). Correlation studies between the stages of fibrosis and values of different laboratory markers revealed no significant associations between the two (Table 3).

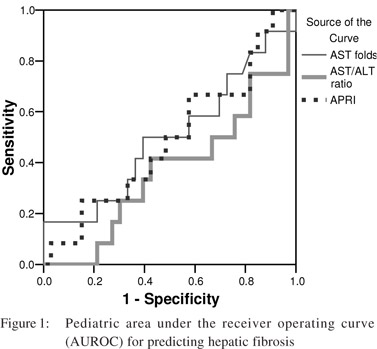

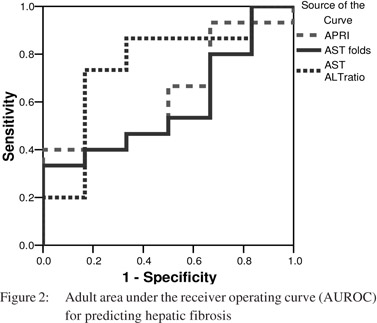

The area under the receiver operator curve (AUROC) for predicting significant fibrosis in pediatric patients was 0 5 for AST levels, 0.37 for AST/ALT ratio and 0.49 for APRI (p = 0.99, 0.18 and 0.9 respectively) (Figure 1). Likewise, the AUROC for predicting significant fibrosis in adults was 0.59 for AST levels, 0.76 for AST/ALT ratio and 0.63, for APRI (p = 0.5, 0.07 and 0.35 respectively) (Figure 2). As the AUROC was not significant for either of the patient groups, we couldn’t conclude a best cutoff for neither adult ROC nor pediatric curves.

Discussion

In the present study we tried to assess the validity of noninvasive, simple, easily available blood tests to predict significant fibrosis in a consecutive series of treatment-naïve CHC patients. One hundred and thirteen patients suffering from chronic viral hepatitis C were included in this study. They included 76 children [comprising of 28 without any evidence of fibrosis on liver biopsy and 48 showing mild to moderate fibrosis (Metavir score 1-2)]; and 37 adults [comprising of 12 with moderate fibrosis (score 2) on liver biopsy and 35 with severe fibrosis (Metavir score 3-4)].

The AST levels were higher in patients who showed significant liver fibrosis than in patients with insignificant fibrosis, both among pediatric and adult patients; however the difference did not reach statistical significance. Kamimoto et al

[17] demonstrated that progression of liver fibrosis may reduce the clearance of AST, leading to increased serum AST levels. In addition, advanced liver disease may be associated with mitochondrial injury, resulting in more marked release of AST, which is predominantly present in mitochondria and cytoplasm, whereas ALT is solely located in the cytoplasm.[18,19] We didn’t find any difference between the AST/ALT ratio in children with hepatic fibrosis and those without fibrosis. Similarly we did not find any significant difference in the AST/ALT ratio in adult patients with moderate and evere hepatic fibrosis. Our study results conform to many precious studies which report that AST/ALT ratio failed to predict the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C.[9,10,11]

While some authors have reported that an AST/ALT ratio >1 may suggest the presence of cirrhosis and have demonstrated positive correlation with both histological stage and clinical evaluation,

[20,21,22] several others have concluded that an AST/ALT ratio >1 may not be as useful for predicting cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C. The results of latter support the need for liver biopsy prior to treatment of chronic hepatitis C, since the AST/ALT ratio failed to accurately predict the presence of cirrhosis in their patients.[23,24]

We investigated the relationship between the stage of fibrosis, AST level and platelet count by employing the APRI devised by Wai et al.

[13] Although the AUROC curve for predicting significant hepatic fibrosis was much lower in pediatric patients (AUROC 0.49, p = 0.9) than in adult patients (AUROC 0.63, p =0.35), but both failed to reliably predict significant fibrosis in these patient groups.

Bourliere et al

[25] reported that noninvasive markers of fibrosis may have different diagnostic accuracy depending on the prevalence of significant fibrosis in the population under study and that a normal AST value can lead to APRI inaccuracy. Chrysanthas et al,[26] Sebastiani et al,[27] Lackner et al,[28] and Pohl et al[11] concluded that simple laboratory tests may render liver biopsy unnecessary only in a minority of patients with CHC but the need for liver biopsy even if reduced, cannot be completely avoided. Al-Mahtab et al[29] concluded from their study that APRI does not appear to be of use in predicting fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. They contended that the probable reason for lack of correlation between APRI and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B is the platelet count which was not decreased in their group of patients. Shaheen et al30 systematically reviewed studies comparing FibroTest or FibroScan versus biopsy in HCV patients. The authors concluded that FibroTest and FibroScan have excellent utility for the identification of HCV-related cirrhosis, but offer lesser accuracy for early stage disease. They noted that refinements were necessary before these tests could replace liver biopsy.[30] Sporea and colleagues[31] concluded from their study that evaluation of liver fibrosis can be performed both by FibroTest and liver biopsy, the latter being the “gold standard”. They further stated that non-invasive markers of fibrosis may find their utility over the coming years but current recommendations by authorities in the field mandate liver biopsy necessary for the evaluation of chronic hepatitis, despite the fact that it is not a perfect test. On the other hand, numerous studies[32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] have demonstrated that APRI was a good estimator of hepatic fibrosis in patients with CHC. The usage of different histological scoring systems, inter-observer and/or intraobserver variability and differences in patient populations in these studies could be responsible for this disagreement.

Liver biopsy is considered the most accurate modality to estimate the necro inflammatory activity of a pathological hepatic process and the stage of disease involving the liver, by assessing the type and extent of fibrosis along with the recognition of architectural disturbances. Increase in aminotransferase levels do not adequately reflect the disease severity and assays measuring fibrosis-related bio-molecules circulating in the blood are not yet standardized for wide spread clinical use.

[40]

Our study had its limitations. We included only early degree fibrosis cases in the pediatric age group. We also excluded patients with severe coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia that may interfere in performing a safe liver biopsy. Using two different age groups could also affect our results.

In conclusion, the results of our study do not demonstrate any diagnostic role of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) as a simple non-invasive test for diagnosis of liver fibrosis, and liver biopsy remains the gold standard for this purpose. Novel biomarkers of fibrosis are needed for early detection of mild to moderate fibrosis. Acknowledgments The authors thank the patients and their parents for their cooperation during this study.

References

Discussion

In the present study we tried to assess the validity of noninvasive, simple, easily available blood tests to predict significant fibrosis in a consecutive series of treatment-naïve CHC patients. One hundred and thirteen patients suffering from chronic viral hepatitis C were included in this study. They included 76 children [comprising of 28 without any evidence of fibrosis on liver biopsy and 48 showing mild to moderate fibrosis (Metavir score 1-2)]; and 37 adults [comprising of 12 with moderate fibrosis (score 2) on liver biopsy and 35 with severe fibrosis (Metavir score 3-4)].

The AST levels were higher in patients who showed significant liver fibrosis than in patients with insignificant fibrosis, both among pediatric and adult patients; however the difference did not reach statistical significance. Kamimoto et al

[17] demonstrated that progression of liver fibrosis may reduce the clearance of AST, leading to increased serum AST levels. In addition, advanced liver disease may be associated with mitochondrial injury, resulting in more marked release of AST, which is predominantly present in mitochondria and cytoplasm, whereas ALT is solely located in the cytoplasm.[18,19] We didn’t find any difference between the AST/ALT ratio in children with hepatic fibrosis and those without fibrosis. Similarly we did not find any significant difference in the AST/ALT ratio in adult patients with moderate and evere hepatic fibrosis. Our study results conform to many precious studies which report that AST/ALT ratio failed to predict the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C.[9,10,11]

While some authors have reported that an AST/ALT ratio >1 may suggest the presence of cirrhosis and have demonstrated positive correlation with both histological stage and clinical evaluation,

[20,21,22] several others have concluded that an AST/ALT ratio >1 may not be as useful for predicting cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C. The results of latter support the need for liver biopsy prior to treatment of chronic hepatitis C, since the AST/ALT ratio failed to accurately predict the presence of cirrhosis in their patients.[23,24]

We investigated the relationship between the stage of fibrosis, AST level and platelet count by employing the APRI devised by Wai et al.

[13] Although the AUROC curve for predicting significant hepatic fibrosis was much lower in pediatric patients (AUROC 0.49, p = 0.9) than in adult patients (AUROC 0.63, p =0.35), but both failed to reliably predict significant fibrosis in these patient groups.

Bourliere et al

[25] reported that noninvasive markers of fibrosis may have different diagnostic accuracy depending on the prevalence of significant fibrosis in the population under study and that a normal AST value can lead to APRI inaccuracy. Chrysanthas et al,[26] Sebastiani et al,[27] Lackner et al,[28] and Pohl et al[11] concluded that simple laboratory tests may render liver biopsy unnecessary only in a minority of patients with CHC but the need for liver biopsy even if reduced, cannot be completely avoided. Al-Mahtab et al[29] concluded from their study that APRI does not appear to be of use in predicting fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. They contended that the probable reason for lack of correlation between APRI and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B is the platelet count which was not decreased in their group of patients. Shaheen et al30 systematically reviewed studies comparing FibroTest or FibroScan versus biopsy in HCV patients. The authors concluded that FibroTest and FibroScan have excellent utility for the identification of HCV-related cirrhosis, but offer lesser accuracy for early stage disease. They noted that refinements were necessary before these tests could replace liver biopsy.[30] Sporea and colleagues[31] concluded from their study that evaluation of liver fibrosis can be performed both by FibroTest and liver biopsy, the latter being the “gold standard”. They further stated that non-invasive markers of fibrosis may find their utility over the coming years but current recommendations by authorities in the field mandate liver biopsy necessary for the evaluation of chronic hepatitis, despite the fact that it is not a perfect test. On the other hand, numerous studies[32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] have demonstrated that APRI was a good estimator of hepatic fibrosis in patients with CHC. The usage of different histological scoring systems, inter-observer and/or intraobserver variability and differences in patient populations in these studies could be responsible for this disagreement.

Liver biopsy is considered the most accurate modality to estimate the necro inflammatory activity of a pathological hepatic process and the stage of disease involving the liver, by assessing the type and extent of fibrosis along with the recognition of architectural disturbances. Increase in aminotransferase levels do not adequately reflect the disease severity and assays measuring fibrosis-related bio-molecules circulating in the blood are not yet standardized for wide spread clinical use.

[40]

Our study had its limitations. We included only early degree fibrosis cases in the pediatric age group. We also excluded patients with severe coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia that may interfere in performing a safe liver biopsy. Using two different age groups could also affect our results.

In conclusion, the results of our study do not demonstrate any diagnostic role of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) as a simple non-invasive test for diagnosis of liver fibrosis, and liver biopsy remains the gold standard for this purpose. Novel biomarkers of fibrosis are needed for early detection of mild to moderate fibrosis. Acknowledgments The authors thank the patients and their parents for their cooperation during this study.

References

- Veldt BJ, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, Reichen J, Hofmann WP, Zeuzem S, et al. Sustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:677–84.

- Missiha SB, Ostrowski M, Heathcote EJ. Disease progression in chronic hepatitis C: modifiable and nonmodifiable factors. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1699–714.

- Wursthorn K, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Natural history: the importance of viral load, liver damage and HCC. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:1063–79.

- Minuk GY. The influence of host factors on the natural history of chronic hepatitis C viral infections. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:271–6.

- Feld JJ, Liang TJ. Hepatitis C — identifying patients with progressive liver injury. Hepatology. 2006;43:S194–206.

- Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1994;20:15–20.

- Westin J, Lagging LM, Wejstal R, Norkrans G, Dhillon AP. Interobserver study of liver histopathology using the Ishak score in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Liver. 1999;19:183–7.

- Regev A, Behro M, Jeffers LJ, Milikowski C, Molina EG, Pyrsopoulos NT, et al. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2614–8.

- Bonacini M, Hadi G, Govindarajan S, Lindasy KL. Utility of a discriminant score for diagnosing advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1302–4.

- Wong V, Caronia S, Wight D, Palmer CR, Petrik J, Britton P, et al. Importance of age in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 1997;4:255–64.

- Pohl A, Behling C, Oliver D, Kilani M, Monson P, Hassanein T. Serum aminotransferases levels and platelet count as predictors of degree of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3142–6.

- Forns X, Ampurdanes S, Llovet JM, Aponte J, Quintó L, Martínez-Bauer E, et al. Identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model. Hepatology. 2002;36:986–92.

- Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–26.

- Hui AY, Liew CT, Go MY, Chim AM, Chan HL, Leung NW, et al. Quantitative Assessment of Fibrosis in Liver Biopsies From Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2004;24:611–8.

- Hegarty JE, Williams R. Liver biopsy: techniques, clinical applications, and complications. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:1254–6.

- Kaplan MM, Bonis PA. Histologic Scoring Systems for Chronic Liver Disease. UpToDate. Accessed: March 29, 2009.

- Kamimoto Y, Horiuchi S, Tanase S, Morino Y. Plasma clearance of intravenously injected aspartate aminotransferase isoenzyme: evidence for preferential uptake by sinusoidal liver cells. Hepatology. 1985;5:367–75.

- Okuda M, Li K, Beard MR, Showalter LA, Scholle F, Lemon SM, et al. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:366–75.

- Nalpas B, Vassault A, Le Guillou A, Lesgourgues B, Ferry N, Lacour B, et al. Serum activity of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase: a sensitive marker of alchoholism with or without alchoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1984;4:893–6.

- Zechini B, Pasquazzi C, Aceti A. Correlation of serum aminotransferases with HCV RNA levels and histological findings in patients with chronic hepatitis C: the role of serum aspartate transaminase in the evaluation of disease progression. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:891–6.

- Park GJ, Lin B P, Ngu MC, Jones DB, Katelaris PH. Aspartate aminotransferase: alanine aminotransferase ratio in chronic hepatitis C infection: is it a useful predictor of liver cirrhosis? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:386–90.

- Giannini E, Risso D, Botta F, Chiarbonello B, Fasoli A, Malfatti F, et al. Validity and clinical utility of aspartate aminotransferasealanine aminotransferase ratio in assessing disease severity and prognosis in patients with hepatitis C virus- related chronic liver disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:218–24.

- Imperiale TF, Said AT, cummings OW, Born LJ. Need for validation of clinical decision aids: use of the AST/ALT ratio in predicting cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C. AMJ Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2328–32.

- Reedy DW, Loo AT, Levine RA. AST/ALT ratio > or = 1 is not diagnostic of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2156–9.

- Bourliere M, Penaranda G, Renou C, Botta-Fridlund D, Tran A, Portal I, et al. Validation and comparison of indexes for fibrosis and cirrhosis prediction in chronic hepatitis C patients: proposal for a pragmatic approach classification without liver biopsies. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:659–70.

- Chrysanthos NV, Papatheodoridis GV, Savvas S, Kafiri G, Petraki K, Manesis EK, et al. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index for fibrosis evaluation in chronic viral hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:389–96.

- Sebastiani G, Vario A, Guido M, Noventa F, Plebani M, Pistis R, et al. Stepwise combination algorithms of non-invasive markers to diagnose significant fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:686–93.

- Lackner C, Sturber G, Liegl B, Leibl S, Ofner P, Bankuti C, et al. Comparison and validation of simple noninvasive tests for prediction of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1376–82.

- Al-Mahtab M, Shrestha A, Rahman S, Khan M, Kamal M. APRI is not a Useful Predictor of Fibrosis for Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B. Hepatitis Monthly. 2009;3:185–8.

- Shaheen AA, Wan AF, Myers RP. FibroTest and FibroScan for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review of diagnostic test accuracy. Am J Gastroenterol.2007;102:2589–600.

- Sporea I, Popescu A, Sirli R. Why, who and how should perform liver biopsy in chronic liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3396–402.

- Silva Jr RG, Fakhouri R, Nascimento TV, Santos IM, Barbosa J LM. Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for fibrosis and cirrhosis prediction in chronic hepatitis C patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:15–9.

- Karoui S, Taieb Jomni M, Bellil K, Haouet S, Boubaker J, Filali A. Predictive factors of fibrosis for chronic viral hepatitis C. Tunis Med. 2007;85:454–60.

- Schiavon LL, Schiavon JL, Filho RJ, Sampaio JP, Lanzoni VP, Silva AE, et al. Simple blood tests as noninvasive markers of liver fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2007;46:307–14.

- Abdo AA, Al Swat K, Azzam N, Ahmed S, Al faleh F, et al. Validation of three noninvasive laboratory variables to predict significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:89–93.

- Parise ER, Oliveira AC, Figueiredo-Mendes C, Lanzoni V, Martins J, Nader H, et al. Noninvasive serum markers in the diagnosis of structural liver damage in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int. 2006;26:1095–9.

- Snyder N, Gajula L, Xiao SY, Grady J, Luxon B, Lau DT, et al. APRI: an easy and validated predictor of hepatic fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:535–42.

- McGoogan KE, Smith PB, Choi SS, Berman W, Jhaveri R. Performance of the AST-to-platelet ratio index as a noninvasive marker of fibrosis in pediatric patients with chronic viral hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:344–6.

- Vardar R, Vardar E, Demiri S, Sayhan SE, Bayol U, Yildiz C, et al. Is there any non-invasive marker replace the needle liver biopsy predictive for liver fibrosis, in patients with chronic hepatitis? Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1459–65.

- Rockey DC, Bissell DM. Noninvasive measures of liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S113–20.

|

|

|

|

|

|