|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Bala Natarajan, Tommy H Lee, Sumeet K Mittal

Department of Surgery, Creighton University,

Omaha, Nebraska, NE 68131, USA

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Sumeet K Mittal

Email: SumeetMittal@creighton.edu

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/

48uep6bbphidvals|472 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Submucosal dissection of the esophageal mucosa can be purposeful for submucosal endoscopy,[1, 2] but more commonly occurs inadvertently. Diagnostic endoscopy is a safe procedure with a low complication rate of about 0.1%.[3] Perforation of the esophagus during diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is rare and occurs in about 0.03% of cases.[4] Endoscopic management of circumferential submucosal dissection has been described in the past but not to the extent of mucosal inversion.[5] We report the first case of iatrogenic inversion of esophageal mucosa along the entire length of esophagus during a diagnostic EGD.

Case Report

A 70 yr old female was emergently transferred to the esophageal center for management of an iatrogenic esophageal injury. Earlier in the day she had undergone an upper endoscopy for evaluation of dysphagia. Described in the endoscopy report was a mild stricture at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) through which the endoscope was advanced with gentle pressure and minimal resistance. The endoscope was advanced through the esophagus into the stomach. On retroflex view a grayish discolored “sheath” covering the endoscope was noticed extending from the gastroesophageal junction into the stomach. A diagnosis of significant mucosal injury was suspected and the endoscope removed. The patient was intubated and immediately transferred to our center.

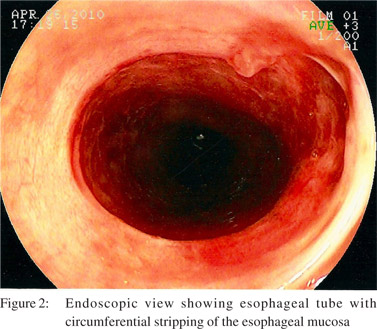

The patient’s past medical history was significant for wellcontrolled supraventricular tachycardia. She reported a nearly 20-year history of mild to moderate cervical dysphagia without weight loss. Medications included lopressol, inhaled triamcinolone, aspirin, lorazepam, verapamil and lansoprazole. She did not have a history of anemia or significant allergies. Evaluation revealed an anxious, intubated patient, with normal WBC count, temperature and heart rate. There was no neck tenderness or crepitus. Chest radiography and electrocardiogram were normal, while a computerized tomogram (CT) showed an edematous esophageal tube without mediastinal air and evidence of prolapsed esophageal mucosa in the stomach (Figures 1). The patient was taken to the operating room. During upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (Fujinon® endoscopy system EPX 2200 with EG250WR5 scope), an absence of esophageal mucosa was noted starting about 1 cm from the UES. There was a blood clot seen within the lumen (Figure 2). The endoscope could not be safely advanced beyond 25 cm from incisors due to difficulties in

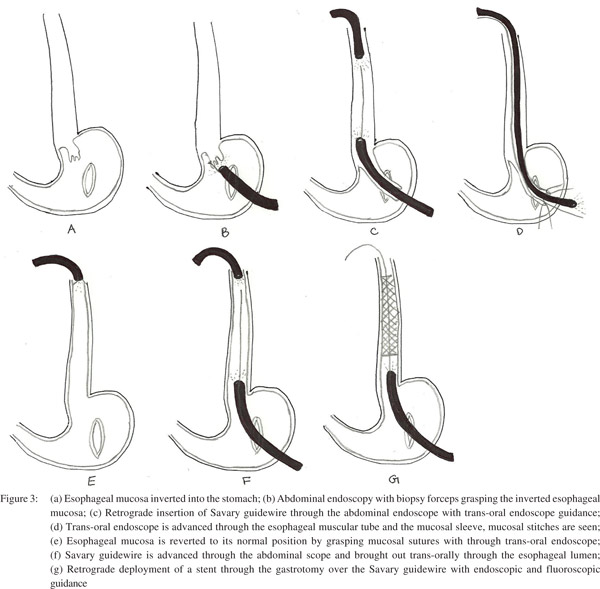

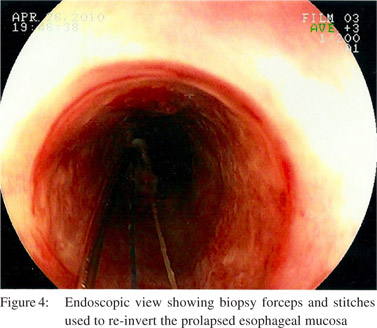

visualization and identifying the true esophageal lumen. Through a limited upper abdominal laparotomy a 5 cm gastrotomy was made and a second sterile endoscope inserted into the stomach. The inverted esophageal mucosa was visualized (Figure 3a). This mucosa was held with an endoscopic snare and brought out through the gastrotomy (Figure 3b). The abdominal endoscope was passed through the mucosal tube and advanced retrograde into the proximal esophagus. The trans-oral endoscope was then advanced and both scopes made to face each other in the proximal esophageal lumen. A savory guidewire was passed through the abdominal scope and fed retrograde through working channel of the transoral endoscope (Figure 3c). With the help of the guidewire, the trans-oral endoscope was advanced through the esophageal muscular tube and eventually into the lumen of the mucosal sleeve as the abdominal scope was withdrawn. Two sutures were placed at the esophageal mucosal edge and were left long (Figure 3d). These sutures were grasped with a biopsy forceps (Boston Scientific Radical Jaw ®) passed through the trans-oral endoscope (Figure 4). This endoscope was then withdrawn in the cephalad direction and the esophageal mucosa was re-inverted to its normal position (Figure 3e). The sutures were then delivered retrograde and passed out through the nares and looped around the ear to keep them in place. Mucosal retraction resulted in an approximately 3 cm bare area of exposed muscularis at the proximal esophagus. A removable stent was placed to hold the mucosa in place. Trans-oral placement of the stent would have applied shear against our re-apposed mucosa, hence the stent was advanced and deployed retrograde through the gastrotomy.

The abdominal endoscope was re-inserted through the gastrotomy and the gastroesophageal junction was entered in a retrograde manner. A Savary guidewire was advanced through the abdominal scope and brought out trans-orally through the esophageal lumen (Figure 3f). A Boston scientific polyflex® esophageal stent with 16 mm diameter, 20 mm flare and 12 cm length was loaded in a retrograde manner such that the flare would deploy first and would lie in the proximal esophagus. Prior to loading, a long silk suture was attached to the flare of the stent. Under fluoroscopic guidance, the stent was passed through the gastrotomy over the Savary guidewire and was deployed (Figure 3g). The proximal end of the stent was 14.5 cm from the incisors (at the upper end of the upper esophageal sphincter). The distal end of the stent was at 27 cm from the incisors. The suture at the proximal flare of the stent was brought out through the nose and hooked around the ear and taped securely. This maneuver has been previously employed by us to prevent stent migration. A trans-oral endoscopy was performed through the stent and the restored esophageal mucosal lining into the stomach. A small, non-obstructing hematoma was seen bulging below the stent on the right side of the esophageal mucosal wall that was expected to resolve with conservative management. The gastrotomy was closed in 2 layers with absorbable sutures. A stamm gastrostomy was placed through a separate gastric opening and a jejunostomy tube was inserted 20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. Post-operatively, antibiotics were continued for 3 days and nutrition was provided through the jejuostomy tube. The gastrostomy tube was left to dependent drainage. The patient underwent transnasal endoscopy (TNE) on the second and fourth postoperative days. Minimal esophageal mucosal erosion was identified at the inferior portion of the stent. A repeat endoscopy was done on the eighth postoperative day and the esophageal stent was removed. Persistent deepithelization of the proximal esophagus for about 3-4 cm was observed. Subsequent TNE 6 days later (2 weeks after the initial injury) showed a normal viable esophageal mucosa. A gastrograffin swallow study was performed and did not show evidence of leak. The patient was discharged home on a full liquid diet at 2 weeks from her initial injury. She was started on a soft diet when she was seen in the clinic 1 month after surgery. She underwent an EGD 6 weeks after her initial injury that revealed 2 short strictures in the mid esophagus, thought to correlate with the distal extent of the previous stent, which were dilated to 45 Fr using a Savary dilator. Biopsies were taken which revealed normal esophageal mucosa. A repeat EGD after an additional 4 weeks showed a completely healed esophagus with a normal caliber. The patient has been free of dysphagia and is tolerating her diet nearly 9 months after the initial presentation. Esophageal biopsies did not show any abnormality.

The abdominal endoscope was re-inserted through the gastrotomy and the gastroesophageal junction was entered in a retrograde manner. A Savary guidewire was advanced through the abdominal scope and brought out trans-orally through the esophageal lumen (Figure 3f). A Boston scientific polyflex® esophageal stent with 16 mm diameter, 20 mm flare and 12 cm length was loaded in a retrograde manner such that the flare would deploy first and would lie in the proximal esophagus. Prior to loading, a long silk suture was attached to the flare of the stent. Under fluoroscopic guidance, the stent was passed through the gastrotomy over the Savary guidewire and was deployed (Figure 3g). The proximal end of the stent was 14.5 cm from the incisors (at the upper end of the upper esophageal sphincter). The distal end of the stent was at 27 cm from the incisors. The suture at the proximal flare of the stent was brought out through the nose and hooked around the ear and taped securely. This maneuver has been previously employed by us to prevent stent migration. A trans-oral endoscopy was performed through the stent and the restored esophageal mucosal lining into the stomach. A small, non-obstructing hematoma was seen bulging below the stent on the right side of the esophageal mucosal wall that was expected to resolve with conservative management. The gastrotomy was closed in 2 layers with absorbable sutures. A stamm gastrostomy was placed through a separate gastric opening and a jejunostomy tube was inserted 20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. Post-operatively, antibiotics were continued for 3 days and nutrition was provided through the jejuostomy tube. The gastrostomy tube was left to dependent drainage. The patient underwent transnasal endoscopy (TNE) on the second and fourth postoperative days. Minimal esophageal mucosal erosion was identified at the inferior portion of the stent. A repeat endoscopy was done on the eighth postoperative day and the esophageal stent was removed. Persistent deepithelization of the proximal esophagus for about 3-4 cm was observed. Subsequent TNE 6 days later (2 weeks after the initial injury) showed a normal viable esophageal mucosa. A gastrograffin swallow study was performed and did not show evidence of leak. The patient was discharged home on a full liquid diet at 2 weeks from her initial injury. She was started on a soft diet when she was seen in the clinic 1 month after surgery. She underwent an EGD 6 weeks after her initial injury that revealed 2 short strictures in the mid esophagus, thought to correlate with the distal extent of the previous stent, which were dilated to 45 Fr using a Savary dilator. Biopsies were taken which revealed normal esophageal mucosa. A repeat EGD after an additional 4 weeks showed a completely healed esophagus with a normal caliber. The patient has been free of dysphagia and is tolerating her diet nearly 9 months after the initial presentation. Esophageal biopsies did not show any abnormality.

Discussion

Our case is unique in several ways. This is the first report of a patient with circumferential submucosal dissection along the entire length of the esophagus with mucosal inversion into the stomach due to an endoscopic intervention. Kim et al[6] described a case of spontaneous circumferential intramural esophageal dissection where the mucosa was not inverted. They managed the patient conservatively initially followed by endoscopic dilation and stent placement when conservative management failed.

In our patient, the injury was caused by EGD, which is unusual. Submucosal dissection of the esophagus after EGD was reported by Tang et al.[7] They visualized the injury by combined oral and retrograde endoscopy, but managed it conservatively. Subsequent stricture development was treated with endoscopic dilatation. We elected to operate on this patient immediately because of the severity of the injury seen on initial endoscopy.

The combination of transoral and retrograde endoscopy for repositioning of the esophageal mucosal has not been previously described in literature. While more radical surgical approaches involving either resection or bypass of the esophagus with construction of a gastric conduit were considered, we elected to attempt a less radical approach to spare the patient the considerable morbidity associated with these options. While our combined surgical and doubleendoscopic approach was successful, it does require two

highly-skilled endoscopists. An even less invasive strategy of simply excising the stripped mucosa was considered, but it was felt that with circumferential stripping along the entire length of the esophagus development of a long, complicated stricture was likely.

In conclusion, complete mucosal stripping and inversion is a previously unreported complication of EGD. A combined endoscopic and surgical approach is technically challenging and best performed by either surgeons with endoscopic skills or with close collaboration between surgeons and gastroenterologists.

References

Discussion

Our case is unique in several ways. This is the first report of a patient with circumferential submucosal dissection along the entire length of the esophagus with mucosal inversion into the stomach due to an endoscopic intervention. Kim et al[6] described a case of spontaneous circumferential intramural esophageal dissection where the mucosa was not inverted. They managed the patient conservatively initially followed by endoscopic dilation and stent placement when conservative management failed.

In our patient, the injury was caused by EGD, which is unusual. Submucosal dissection of the esophagus after EGD was reported by Tang et al.[7] They visualized the injury by combined oral and retrograde endoscopy, but managed it conservatively. Subsequent stricture development was treated with endoscopic dilatation. We elected to operate on this patient immediately because of the severity of the injury seen on initial endoscopy.

The combination of transoral and retrograde endoscopy for repositioning of the esophageal mucosal has not been previously described in literature. While more radical surgical approaches involving either resection or bypass of the esophagus with construction of a gastric conduit were considered, we elected to attempt a less radical approach to spare the patient the considerable morbidity associated with these options. While our combined surgical and doubleendoscopic approach was successful, it does require two

highly-skilled endoscopists. An even less invasive strategy of simply excising the stripped mucosa was considered, but it was felt that with circumferential stripping along the entire length of the esophagus development of a long, complicated stricture was likely.

In conclusion, complete mucosal stripping and inversion is a previously unreported complication of EGD. A combined endoscopic and surgical approach is technically challenging and best performed by either surgeons with endoscopic skills or with close collaboration between surgeons and gastroenterologists.

References

- Gutierrez del Olmo A, Loscos JM, Baki W, Nazal R, Nisa E,Ramirez-Armengol JA. Spontaneous intramural oesophageal perforation. Endoscopy. 1985;17:76–7.

- Sumiyama K, Gostout CJ, Rajan E, Bakken TA, Knipschield MA, Marler RJ. Submucosal endoscopy with mucosal flap safety valve. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2007;65:688–94.

- Costamagna G, Marchese M. Management of esophageal perforation after therapeutic endoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:391–2.

- Hart R, Classen M. Complications of diagnostic gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1990;22:229–33.

- Shahmir M, Schuman BM. Complications of fiberoptic endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1980;26:86–91.

- Kim SH, Lee SO. Circumferential intramural esophageal dissection successfully treated by endoscopic procedure and metal stent insertion. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1065–9.

- Tang SJ, Tang L, Jazrawi SF, Meyer D, Wait MA, Myers LL. Iatrogenic esophageal submucosal dissection after attempted diagnostic gastroscopy (with videos). Laryngoscope. 2009;119:36–8.

|

|

|

|

|

|