48uep6bbphidvals|371

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

HNPCC (Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer) also called as Lynch syndrome is a rare inherited condition that increases risk of colon cancer and other cancers. An estimated 2% to 3%of colon cancers are thought to be caused by Lynch syndrome. Families that have Lynch syndrome usually have more cases of colon cancer than would normally be expected. The average age of diagnosis of cancer in patients with this syndrome is 44 years as compared to 64 years in people without the syndrome.1 People with Lynch syndrome may experience, a family history of colon cancer, endometrial cancer, other related cancers, including ovarian cancer, renal cancer, stomach cancer, small bowel cancer, liver cancer or other cancers that occurs at a young age. Lynch syndrome runs in families in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. HNPCC is caused by a germline mutation in a mismatch repair gene or is associated with tumours exhibiting Microsatellite Instability (MSI). HNPCC is known to be associated with mutations in four genes involved in the mismatch repair pathway (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2).

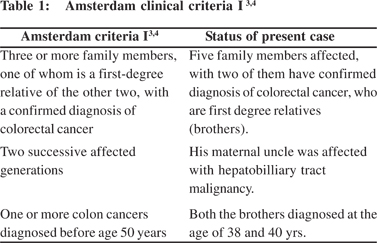

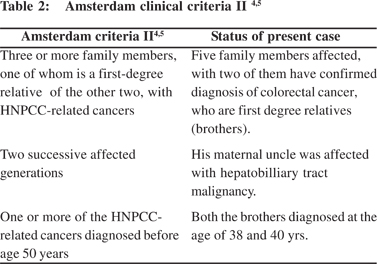

The diagnosis of HNPCC can be made on the basis of the Amsterdam Clinical Criteria or by molecular genetic testing for germline mutations in one of the several mismatch repair (MMR) genes.[2]

Case Report

A 38-year-old male patient presented with complaints of intermittent blood in stools since 1 year, loose motions since 1 month, passage of undigested food in faeces since 1 month, and pain in left hypochondrium since 15 days. Patient gave history of occasional consumption of alcohol since 20 yrs. There was no history of hematemesis. Patient underwent colonoscopy 1 year back which showed friable, circumferential,ulcerated growth with significant luminal narrowing at splenic flexure (45 cm from anus), but the patient did not take any treatment till 1 year after the procedure. A more detailed history from the patient revealed that many members of his family were affected by cancer. His elder brother had been diagnosed with moderately differentiating adenocarcinoma of the caecum at 40 years of age, and had undergone right hemicolectomy. His sister was diagnosed with carcinoma endometrium and had undergone hysterectomy. His maternal uncle was suffering from jaundice, and had died of hepatobiliary malignancy. His sister has been operated twice for ovarian cancer at the age of38 years and had eventually died. His maternal uncle’s son was diagnosed with an occult primary in the scalene lymph node at the age of 21, showing adenocarcinomatous histopathology.

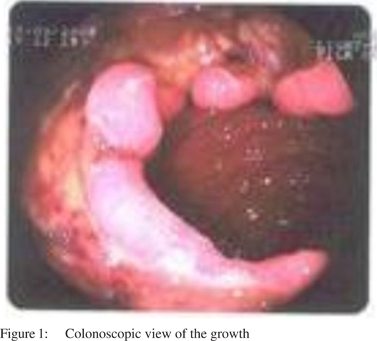

One year after his initial presentation, the patient underwent repeat colonoscopy, which showed ulcerated friable growth in splenic flexure ~45 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1). A gastrocolic fistula was suspected on endoscopy.

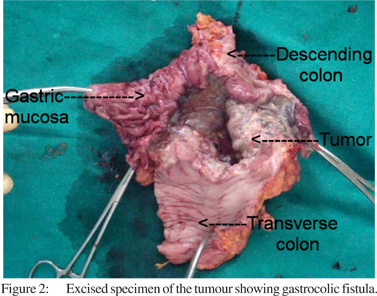

On USG and contrast CT there were no liver or lymph node metastasis. Histopathology revealed moderately differentiating adenocarcinoma of the decending colon. As per the Amsterdam criteria I[3,4] and II[4,5] the patient was diagnosed as having Lynch syndrome and was taken up for surgery. Intraoperative findings were suggestive of gastocolic fistula and no other synchronous growth was found (Figure 2).

Left extended hemicolectomy with partial gastrectomy was performed. The post-operative period was uneventful and patient was discharged on the 10th post-operative day. Histopathology reports showed adenocarcinoma with mesenteric metastasis. The patient was advised chemother apyand is currently on regular chemotherapy.

Discussion

Lynch syndrome is a rare condition responsible for approximately 2–7% of all diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer. It is caused by a germline mutation in a mismatch repair gene or associated with tumours exhibiting MSI and is characterized by an increased risk of colon cancer and other cancers (endometrium, ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, upper urinary tract, brain and skin). Individuals with Lynch Syndrome have an approximately 80% lifetime risk for colon cancer. The average age of diagnosis of colorectal cancer is 61 years. Women with Lynch Syndrome have a 20 - 60% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer.[2] The average age of diagnosis of endometrial cancer is 46 - 62 years. Among women with Lynch Syndrome who develop both colon cancer and endometrial cancer, approximately 50% present first with endometrial cancer. Lynch Syndrome associated ovarian cancers have a mean age of 42.5 years at diagnosis with approximately 30% diagnosedbefore 40 years.[2]

The diagnosis of Lynch Syndrome can be made on the basis of the Amsterdam Clinical Criteria (Table 1 and 2) or by molecular genetic testing for germline mutations in one the of several mismatch repair (MMR) genes.

Amsterdam II criteria has taken a broader view for diagnosis of Lynch syndrome, by including HNPCC related cancer.

The revised Bethesda Guidelines were laid down for testing colorectal tumors for microsatellite instability (MSI).[6]The guidelines state that tumors from individuals should be tested for MSI in the following situations:

I. Colorectal cancer diagnosed in an individual younger than age 50 years.

II. Presence of synchronous, metachronous colorectal, or other HNPCC-associated tumours (HNPCC cancers including colorectal, endometrial, stomach, ovarian, pancreas, ureter and renal pelvis, biliary tract, and brain (usually glioblastoma), regardless of age.

III. Colorectal cancer with the MSI-High (MSI-H) histology (presence of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, Crohn’s-like lymphocytic reaction, mucinous/signet-ring differentiation, or medullary growth pattern) diagnosed in a patient younger than age 60 years.

IV. Colorectal cancer diagnosed in one or more first-degree relatives with an HNPCC-related tumour, with one cancer diagnosed before age 50 years.

V. Colorectal cancer diagnosed in two or more first- or seconddegree relatives of any age.

Approximately 90% of colon cancers from families meeting Amsterdam Criteria are Microsatellite instability-High (MSIH).[7,8,9,10] The clinical history of this patient also suggests that this case fulfils the updated Bethesda Guidelines (2004). Hence, clinically it appears to be a case of Lynch syndrome. The patient is under follow up since last 3 months and has been advised colonoscopy every year for recurrence.

If colon cancer is detected, full colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is recommended in these patients.[11,12,13] Prophylactic removal of the colon prior to the development of cancer is generally not recommended for individuals in families having Lynch syndrome because routine colonoscopy is an effective preventive measure.[2] The patients having strong family history, which meets Amsterdam II criteria, are advised to undergo a repeat colonoscopy every year.[1]

A detailed family history, with the help of Amsterdam criteria can help clinicians to diagnose this disease, when genetic testing may not be available or forthcoming in such patients.

References

1. Karpov OO, Limauro DL, Colatrella AM. Uncovering the Lynch syndrome patient. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:214–20.

2. Kohlmann W, Gruber SB. Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer;GeneReviews. 2006 Nov. Available from: http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1211.

3. Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, Khan PM, Lynch HT. The International Collaborative Group on hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (ICG-HNPCC). Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:424–5.

4. Chang G, Shelton A, Welton M. Large intestine. In: Doherty GM, editor. Current diagnosis and treatment surgery. New York: McGraw Hill;2006.p.697.

5. Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1453–6.

6. Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Ruschoff J, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261–8.

7. Thibodeau SN, Bren G, Schaid D. Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science. 1993;260:816–9.

8. Aaltonen LA, Peltomaki P, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Jass JR, Green JS, et al. Replication errors in benign and malignant tumors from hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1645–8.

9. Liu B, Parsons R, Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides NC, Lynch HT, Watson P, et al. Analysis of mismatch repair genes in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med. 1996;2:169–74.

10. unningham JM, Kim CY, Christensen ER, Tester DJ, Parc Y, Burgart LJ, et al. The frequency of hereditary defective mismatch repair in a prospective series of unselected colorectal carcinomas. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:780–90.

11. Lynch HT, Watson P, Kriegler M, Lynch JF, Lanspa SJ, Marcus J, et al. Differential diagnosis of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome I and Lynch syndrome II). Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:372–7.

12. Aarnio M, Mecklin JP, Aaltonen LA, Nystrom-Lahti M, Jarvinen HJ. Life-time risk of different cancers in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:430–3.

13. Church J, Simmang C. Practice parameters for the treatment of patients with dominantly inherited colorectal cancer (familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer). Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1001–12.