48uep6bbphidvals|368

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), and indeterminate colitis.[1]

Although the etiology of IBD has not been well defined, it has been suggested that it can be triggered by environmental, genetic, and immunologic factors.[2] The highest incidence of both CD and UC has been reported from the Northern Europe, United Kingdom, and North America.[3,4] However, recent studies demonstrated that the incidence of IBD is increasing in other parts of the world as well.[5,6,7] In spite of the increasing trend in other parts of the globe, there are limited data regarding epidemiology and clinical feature of IBD from underdeveloped countries4and the pattern of IBD has not been well illustrated in these countries. Studying the epidemiologic profile of IBD including UC in different areas may help researchers to identify etiologic factors of these diseases.[6]

Although the reason for this increasing trend is not clear, some theories suggested that improvements in general health and hygiene are contributing factors for increasing incidence of IBD. Urbanization, exposure to certain infections such as measles, industrialization, and adaptation of western lifestyle have all been incriminated as probable factors that influence incidence of IBD.[2,8]

Similar to other parts of the globe, previous reports from Iran demonstrated increasing incidence of UC in Iran.[2,9,10] Since these studies were performed in referral centers in Tehran, capital of Iran, the studied samples may not have been fully representative of Iranian society, as Iran is a wide geographic country of different ethnicities. Thus, it seems that further studies with a focus on clinical features of IBD are needed to elucidate the pattern of IBD including UC in Iran. In the present study, therefore, we aimed to determine the epidemiologic profile and clinical features of UC in patients who presented to a medical office in Northwest of Iran.

Methods

This retrospective study covered the time period from 1998 to 2008 and included all patients of UC who presented to a private gastroenterology referral clinic in northwest Iran, and were diagnosed with UC either at presentation or later. Patients with the diagnosis of CD were not included due to their low numbers. Patients with incomplete records were also excluded. Demographics, habits and past medical history,colonoscopic findings, major extra-intestinal manifestations (musculoskeletal, mucocutaneous, hepatic, ophthalmic, andurinary tract involvement), severity of disease, treatment details, and duration of follow up were obtained by reviewing the patients records.

The diagnosis of UC was made if patients had history of diarrhea or presence of blood and pus, or both, in the stool for more than 4 weeks; presence of characteristic colonoscopic features with diffusely granular, friable, or ulcerated mucosa with rectal involvement and absence of skip lesions; and histopathologic findings compatible with diagnosis of UC on biopsy.[6] Severity of UC was determined as previously described by Edwards and Truelove.[11]

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL.) version 15. Numerical data has been expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Spearman correlation and Lamda statistic were used to analyze data. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

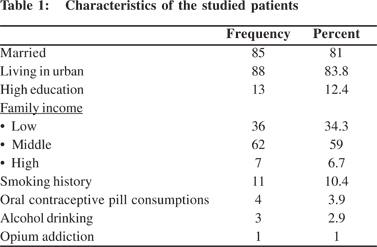

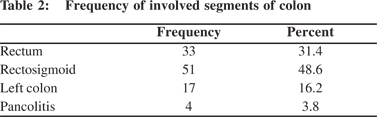

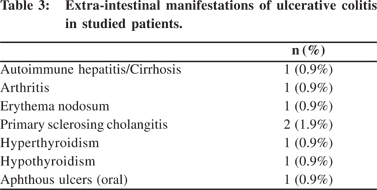

A total of 105 patients including 61 females (58.1%) were evaluated. Mean age of the patients was 33.5 ± 13.1 years (range 12 to 80 years). Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of our study subjects. No patient had history of either tonsillectomy or appendectomy. The median time interval from initiation of symptoms to diagnosis was 9 months (range 1 to 120 months). Mean duration of follow up ranged from 3 to 108 months with a mean of 41.8±24.0 months. Table 2 demonstrates the frequency of involvement of various segments of colon in the patients. As the table shows, the rectosigmoid was the most frequent segment. Among extraintestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis, sclerosing cholangitis had the highest frequency and was found in 2 (1.9%) patients (Table 3).

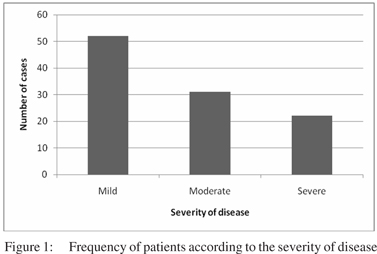

Regarding the type of treatment, all cases had received either Sulfasalazine or Mesalamine while only 24 cases (22.9%) had been treated with corticosteroids. Surgery was performed in 2 (1.9%) subjects. Good and moderate responses to treatment were seen in 94 (89.5%) and 9 (8.5%) patients respectively, while 2 patients (1.9%) had refractory disease. Figure 1 depicts the frequency of patients according to the severity of disease. As the figure demonstrates, most of the patients had mild UC.

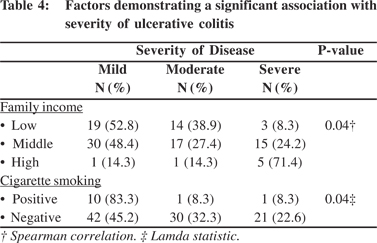

We assessed the association between severity of disease and other study variables. Among all evaluated variables, only family income (the higher the income the more severe the disease) and cigarette smoking (inverse association) were find to have significant association with severity of disease (Table 4). There was no significant association between the prescribed drugs and response to treatment (p=0.06).

Discussion

The present study aimed to describe the epidemiologic profile and clinical presentations of UC in northwest of Iran. In the present study, we found that UC is more frequent in females, which is in agreement with previous reports from Iran.[2,9,12] It is relatively similar to a report from South Korea which showed slight higher incidence of UC in females.[6] However, some studies have failed to note a greater incidence of UC in females.[13,14] Indeed, female predominance has been shown in Crohn’s disease and a role for estrogens and progesterones has been postulated, though it is not the same with UC.[3] In our study, the mean age of patients was 33.5 ± 13.1 years, which is a younger than the mean age of UC patients in another report from Iran.[12]

In our study, 8 patients (7.6%) had extra-intestinal manifestations which is lower than other reports from Iran.[2,9] In the studies conducted by Aghazadeh et al9and Vahedi et al[2], 31.4% and 62.4% of the studied UC patients had extra-intestinal manifestations, respectively. The difference between our results and these reports may be explained by our relatively small sample size, the accuracy of diagnostic evaluations, and difference in definitions. However, our results are relatively close to the incidence reported by Jiang et al. who reviewed 10,218 UC patients.[13] They reported extra-intestinal features in 6.1% of their patients. In the study conducted by Aghzadeh and associates[9], mucocutaneous lesions were the most frequent extra-intestinal feature while Vahedi et al[2] reported the musculoskeletal features as most frequent manifestations. Inour study, primary sclerosing cholangitis was the most common extra-intestinal manifestation.

Rectosigmoid segment of the colon was the most frequently involved part of the colon in our study, and was found involved in 48.6% of the studied patients. Rectum (alone), left colon, and pancolitis were next most frequent sites, similar to previous reports from Iran[2,9] Vahedi and colleagues by evaluating 293 cases of UC reported proctitis in 149, left colitis in 94, and pancolitis in 50 cases.[2] In another report from Iran, Aghazadeh et al. evaluated 283 cases of UC and reported proctitis in 147, involvement of left colon in 85, and pancolitis in 51 cases.[9] In the present study, we found that cigarette smokers have milder disease compared to non-smokers. An inverse association has been reported between cigarette smoking and UC.[3,15,16,17] Although the exact reason for this phenomenon is unclear, some hypotheses such as the effects of nicotine on colonic mucus, rectal blood flow, cytokines, and eicosanoids have been postulated.[3,18] Moreover, other studies have showed that cigarette smoking can influence the course of UC anddecreases hospitalization rates and improve UC symptoms.[19,20] Therefore, our results confirm the previous studies in this regard. However, some authors did not find a significant relation between UC and cigarette smoking.[13] In this study, we also showed an association between family income and severity of UC, with a higher family income bearing relationship with more severe disease. This finding is relatively in agreement with a study by Green et al. that showed an association between high socioeconomic level and risk of UC.[21] In the aforementioned study, socioeconomic status was generated from three components of average family income, unemployment rate, and educational level.[21]

This study attempted to determine the epidemiologic profile and clinical manifestations of UC in northwest of Iran. Our study also showed that family income and smoking can influence the course of UC.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Farzan Institute for Research andTechnology, for technical assistance.

References

1. Fatahzadeh M. Inflammatory bowel disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. Endod. 2009;108:e1–10.

2. Vahedi H, Merat S, Momtahen S, Olfati G, Kazzazi AS, Tabrizian T, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of 500 patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Iran studied from 2004 through 2007. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:454–60.

3. Loftus EVJr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–17.

4. Gismera CS, Aladren BS. Inflammatory bowel diseases: a disease(s) of modern times? Is incidence still increasing? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5491–8.

5. Thia KT, Loftus EV Jr., Sandborn WJ, Yang SK. An update on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3167–82.

6. Yang SK, Hong WS, Min YI, Kim HY, Yoo JY, Rhee PL, et al. Incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis in the Songpa- Kangdong District, Seoul, Korea, 1986-1997. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1037–42.

7. Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Kelly PJ, Ling J. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology and management in an English general practice population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1553–9.

8. Koloski NA, Bret L, Radford-Smith G. Hygiene hypothesis in inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:165–73.

9. Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, Firouzi F. Inflammatory bowel disease in Iran: a review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1691–5.

10. Mir-Madjlessi SH, Forouzandeh B, Ghadimi R. Ulcerative colitis in Iran: a review of 112 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:862–6.

11. Edwards FC, Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299–315.

12. Daryani NE, Bashashati M, Aram S, Hashtroudi AA, Shakiba M, Sayyah A, et al. Pattern of relapses in Iranian patients with ulcerative colitis. A prospective study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:355–8.

13. Jiang XL, Cui HF. An analysis of 10218 ulcerative colitis cases in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:158–61.

14. Ozin Y, Kilic MZ, Nadir I, Cakal B, Disibeyaz S, Arhan M, et al. Clinical features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Turkey. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:157–62.

15. Harries AD, Baird A, Rhodes J. Non-smoking: a feature of ulcerative colitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;284:706.

16. Jick H, Walker AM. Cigarette smoking and ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:261–3.

17. Jiang L, Xia B, Li J, Ye M, Deng C, Ding Y, et al. Risk factors for ulcerative colitis in a Chinese population: an age-matched and sex-matched case-control study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:280–4.

18. Rubin DT, Hanauer SB. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:855–62.

19. Boyko EJ, Perera DR, Koepsell TD, Keane EM, Inui TS. Effects of cigarette smoking on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1147–52.

20. Rudra T, Motley R, Rhodes J. Does smoking improve colitis? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;170:61–63; discussion 66–8.

21. Green C, Elliott L, Beaudoin C, Bernstein CN. A populationbased ecologic study of inflammatory bowel disease: searching for etiologic clues. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:615–23; discussion 624–8.