48uep6bbphidvals|174

48uep6bbphidcol4|ID

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Case Report

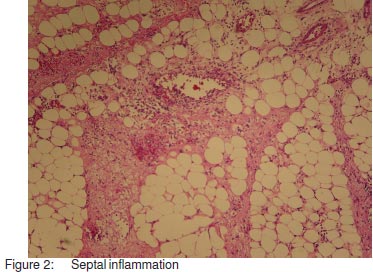

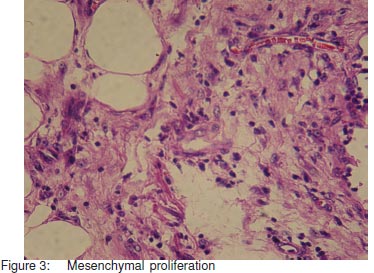

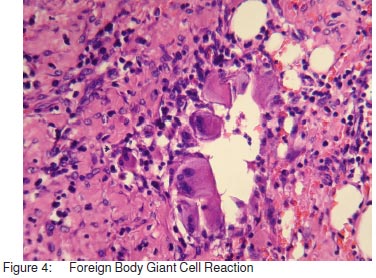

A 40-year-old man presented with complaints of colickyabdominal pain of 3 days duration associated with vomitingand constipation. He had previously undergone 2 surgeries;an appendectomy 5 years ago and repair of enteric perforation1 month earlier. Clinical examination revealed dehydration, apoorly healed midline scar with a 3 cm x 3 cm defect near theumbilicus and a distended abdomen with exaggerated bowelsounds. Plain abdominal radiograph revealed multiple airfluid levels. Ultrasound study of the abdomen revealed dilatedhyperperperistaltic bowel loops and minimal free fluid in theright iliac fossa. A presumptive diagnosis of adhesive smallbowel obstruction was made and the patient was made nilper oral, and subjected to nasogastric suction and parenteralfluids. As he failed to improve despite 48 hours ofconservative management, he was taken up for laparotomy.Peroperative findings revealed minimal ascites,gross thickening of the ileocaecal mesentery, denseadhesions of the terminal ileum, caecum and ascendingcolon to the parietes and to each other; multiple interloopadhesions; and a 6 cm x 5 cm abscess cavity in the rightupper abdomen. Adhesiolysis, drainage of abscess cavity,ileocaecal resection, ileostomy and mucus fistula was done.The patient developed ileostomy diarrhoea in the earlypostoperative period which was managed with high fibre diet,antimotility agents and fluid supplementation,respectively. On the tenth postoperative day, the patientdeveloped features suggestive of septicemic shocknecessitating mechanical ventilation and aggressiveresuscitation measures. Ultrasound study of the abdomendid not reveal any collection. As blood culture was noncontributory, we performed culture of the ileostomy effluentwhich grew Klebsiella sensitive only to carbapenems. Thepatient responded to imipenem which was administered for 2 weeks. He was weaned off the ventilator, allowed normaldiet and subsequently discharged. Histopathology of theresected specimen revealed gross thickening of themesentery of the resected bowel (Figure1). Microscopicexamination revealed septal inflammation (Figure 2),mesenchymal proliferation (Figure 3), foreign body giant cellreaction (Figure 4) and vasculitis (Figure 5) consistent withmesenteric panniculitis. Three months later, the patientunderwent an uneventful restoration of continuity.

Discussion

Mesenteric panniculitis is a poorly understood entity whichwas first described by Jura as “retractile mesenteritis” in1924.[1] The term mesenteric panniculitis was coined byOgden.[2] Known by a variety of terms including isolatedlipodystrophy,[3] mesenteric manifestation of Weber Christiandisease[4] and mesenteric lipogranuloma,[5] it has beendescribed as an idiopathic inflammatory and fibrotic processwhich primarily affects the small bowel mesentery. Accordingto recently published literature, involvement of the colonicmesentery is very rare.[6,7] Other sites of involvement includethe peripancreatic region, omentum, retroperitoneum andpelvis.[8,9,10,11] Less than 300 cases have been describedworldwide till date.[12] Predominantly occurring in middle-agedindividuals, this condition has a slight male predilection. Theproposed aetiological factors of this disease include blunttrauma, prior surgery, allergic disease, autoimmuneprocesses, cold, drugs, vitamin deficiency and vasculitis.[13] Rarely, abdominal tubercular lymphadenitis and autoimmunehemolytic anaemia have been implicated in the pathogenesisof this condition.[14,15] Some authors have proposed thatmesenteric panniculitis represents one phase in a continuumof pathological inflammatory changes affecting the smallbowel mesentery. Initially, there is degeneration ofmesenteric fat i.e lipodystrophy followed by inflammation(panniculitis). Later, fibrosis develops and it is then termedretractile mesenteritis.[16,17,18] Whether retractile mesenteritisand retroperitoneal fibrosis represent two different diseaseentities or the same pathological process is a subject ofcontroversy.[19,20] Clinical features include abdominal pain, backpain, intermittent fever, weight loss, anorexia, vomiting,constipation, diarrhoea, bowel obstruction and occasionally,rectal bleeding while half of the patients present with a poorlydefined abdominal mass.[21,22,23] Sclerosing mesenteritis rarelypresents as chylous ascites.[24] Mesenteric panniculitis hasbeen known to masquerade as intra-abdominal malignancy,retroperitoneal mass, chronic pancreatitis and evenpancreatic cyst. Although a preoperative diagnosis is rarelyestablished, certain characteristic findings on CT scan mayprovide a clue to the disease. The imaging appearancesvary depending on the predominant tissue component (fatnecrosis, inflammation or fibrosis).[25] The common findingsin mesenteric panniculitis include hazy mesenteric infiltration(“misty mesentery”) especially of the jejunal mesentery withdiscrete margins and relative sparing of perivascular fat (“fat-ring sign”). In 50% of cases, a tumour pseudo capsule(“pseudotumoural stripe”) may be present.[26,27] On CT followup, progression of mesenteric panniculitis to fibrosis hasbeen documented in literature.[28] In our case, we mistakenlypresumed adhesions to be the cause of intestinal obstructionand hence, did not obtain a CT scan. The role of CT scan isnot only confined to the diagnosis of this entity, but also noninvasive follow up of the volume, extent, vascular involvementof the mass and identification of potential complications.Radiological differential diagnoses include carcinomatosis,carcinoid tumour, lymphoma, mesenteric oedema andprimary mesenteric mesothelioma.[29] Angiography, MRI andpositron emission tomography have also been used to detectthis clinical entity.[30] The majority of cases however, arediagnosed on histopathological examination. Thepathological findings range from fatty infiltration of themesentery and microscopic infiltration of the fat bylymphocytes, macrophages and foreign body giant cells to aretracted, scarred and adherent mesentery with fat necrosis,fibrosis and calcification.[2] The former pattern was noted inour case. The disease has a benign course although anassociation with malignancy, especially lymphoma has beennoted by some authors.[31,32] There is no consensus on themanagement of patients with mesenteric panniculitis.Patients with minimal symptoms may be followed up withimaging whereas those presenting acutely with intestinalobstruction may require resection, excision or diversion. Inour case, following resection, the patient developedsepticemia probably as a result of Klebsiella enteritis whichmanifested as ileostomy diarrhoea and shock. The diagnosiswas established by culture of ileostomy effluent and thepatient was given appropriate antibiotics which resulted in agood outcome. A thorough search of indexed medical literaturefailed to reveal previous reports of Klebsiella enteritismanifesting as septicemic shock. There are a few case reportsof good response of mesenteric panniculitis to antibiotics,tamoxifen, pentoxifylline, colchicine, oral progestogens, steroidsand immunosuppressants.[15,21,33,34,35,36]

Conclusion

We have presented a case of mesenteric panniculitis whichpresented with intestinal obstruction. The acute presentationwarranted surgical exploration. However, a preoperativediagnosis may have been made with a CT scan of theabdomen. The patient had a stormy postoperative period dueto Klebsiella enteritis and septicemia, which was successfullydiagnosed by culture of the ileostomy effluent. This casehighlights the need to consider alternative causes of intestinalobstruction other than adhesions in a patient who have ahistory of prior surgical intervention. The role of CT scan inthe diagnosis of mesenteric panniculitis as well as theimportance of ileostomy fluid cultures in the diagnosis ofunexplained septicemic shock in patients with ileostomydiarrhoea have also been emphasised

References

-

Jura SV. Mesenterile Retrattile e Sclerosante.

Policlinica (SezPrat). 1924;31:575.

-

Ogden WW, Bradburn DM, Rives JD. Panniculitis of the mesentery.

Ann Surg. 1960;151:659–68.

-

Crane JT, Aguilar MJ, Grimes OF. Isolated lipodystrophy, form ofmesenteric tumor.

Am J Surg. 1955;90:169–79.

-

Herrington JL, Edwards WH, Grossman LA. Mesentericmanifestation of Weber Christian Disease.

Ann Surg.1961;154:949–55

-

Weeks LE, Block MA, Hathaway JC, Rinaldo JA. Lipogranulomaof mesentery producing abdominal Mass.

Arch Surg.1963;86:615–20.

-

Wexner SD, Attiyeh FF. Mesenteric panniculitis of the sigmoidcolon. Report of two cases.

Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:812–5.

-

Karentzos S, Tzoutzos D, Stavropoulos G, Giannakou N, GkicontiI, Giannakakis A. [Mesenteric panniculitis of the sigmoid colon.A case report and review of the literature.] [Article in Italian]

Minerva Chir. 1990;45:1403–6.

-

Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosingmesenteritis: Clinical features, treatment and outcome in ninetytwo patients.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:589–96.

-

Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Sclerosing mesenteritis,mesenteric panniculitis and mesenteric lipodystrophy: a singleentity?

Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:392–8.

-

Vettoretto N, Diana DR, Poiatti R, Matteucci A, Chioda C, GiovanettiM. Occasional finding of Mesenteric lipodystrophy duringlaparoscopy: A difficult diagnosis.

World J Gastroenterol.2007;13:5394–6.

-

Kishimoto K, Hokama A, Irei S, Aoyama H, Tomiyama R, Hirata T,et al. Chronic diarrhoea with thickening of the bowel wall.

Gut.2007;56:94–114.

-

Grieser C, Denecke T, Langrehr J, Hamm B, Hanninen EL.Sclerosing mesenteritis as a rare cause of upper abdominal painand digestive disorders.

Acta Radiol. 2008;23:1–3.

-

Popkharitov AI, Chomov GN. Mesenteric panniculitis of the sigmoidcolon: a case report and review of the literature.

J Med CaseReports. 2007;1:108.

-

Ege G, Akman H, Cakiroglu G. Mesenteric panniculitis associatedwith abdominal tuberculous lymphadenitis: a case report andreview of the literature.

Br J Radiol. 2002;75:378–80.

-

Papadaki HA, Kouroumalis EA, Stefanaki K, RoussomoustakakiM, Daskalogiannaki M, Reppa D, et al. Retractile mesenteritispresenting as fever of unknown origin and autoimmune Haemolyticanaemia.

Digestion. 2000;61:145–8.

-

Thompson GT, Fitzgerald EF, Somers SS. Retractile mesenteritisof the sigmoid colon.

Br J Radiol. 1985;58:266–7.

-

Hartz R, Stryker S, Sparberg M, Poticha SM. Mesenterictumefactions.

Am Surg. 1980;46:525–9.

-

Aach RD, Kahn LI, Frech RS. Obstruction of the small intestinedue to retractile mesenteritis.

Gastroenterology. 1968;54:594–8.

-

Durst AL, Freund H, Rosenmann E, Birnbaum D. Mesentericpanniculitis. Review of the literature and presentation of cases.

Surgery. 1977;81:203–11.

-

Bush RW, Hammar SP, Rudolph RH. Sclerosing mesenteritis.Response to cyclophosphamide.

Arch Intern Med.1986;146:503–5.

-

Mazure R, Fernandez Marty P, Niveloni S, Pedreira S, VazquezH, Smecuol E, et al. Successful treatment of retractile mesenteritiswith oral progesterone.

Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1313–7.

-

Parra-Davila E, McKenney MG, Sleeman D, Hartmann R, Rao RK,McKenney K, et al. Mesenteric panniculitis: Case report andliterature review.

Am Surg. 1998;64:768–71.

-

White B, Kong A, Chang AL. Sclerosing mesenteritis.

AustralasRadiol. 2005;49:185–8.

-

Arora M, Dubin E. A Clinical Case Study: Sclerosing mesenteritispresenting as chylous ascites.

Medscape J Med. 2008;10:30.

-

Mata JM, Inaraja L, Martin J, Olazabal A, Castilla MT. CT featuresof mesenteric panniculitis.

J Comput Assist Tomogr.1987;11:1021–3.

-

Mindelzun RE, Jeffrey RB, Lane MJ, Silverman PM. The mistymesentery on CT: Differential Diagnosis.

Am J Roentgenol.1996;167:61–5.

-

Sabate JM, Torrubia S, Maideu J et al. Sclerosing mesenteritis:imaging finding in 17 patients.

Am J Roentgenol1999;172:625–9

-

Kelly JK, Hwang WS. Idiopathic retractile (sclerosing) mesenteritis and its differential diagnosis.

Am J Surg Pathol.1989;13:513–21.

-

Hamrick-Turner JE, Chiechi MV, Abbitt PL, Ros PR. Neoplasticand inflammatory processes of the peritoneum, omentum andmesentery: diagnosis with CT.

Radiographics.1992;12:1051–68.

-

Ghanem N, Pache G, Bley T, Kotter E, Langer M. MR findings in arare case of sclerosing Mesenteritis of the mesocolon.

J MagnReson Imaging. 2005;21:632–6.

-

Kipfer RE, Moertel CG, Dahlin DC. Mesenteric lipodystrophy.

AnnIntern Med. 1974;80:582–8.

-

Harris RJ, van Stolk RU, Church JM, Kavuru MS. Thoracicmesothelioma associated with abdominal mesenteric panniculitis.

Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2240–2.

-

Venkataramani A, Behling CA, Lyche KD. Sclerosing mesenteritis:an unusual cause of abdominal Pain in an HIV positive patient.

Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1059–60.

-

Kapsoritakis AN, Rizos CD, Delikoukos S, Kyriakou D, KoukoulisGK, Potamianos SP. Retractile Mesenteritis presenting withmalabsorption syndrome: Successful treatment with oralPentoxifylline.

J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2008;17:91–4.

-

Genereau T, Bellin MF, Wechsler B, Le TH, Bellanger J, Grellet J,et al. Demonstration of efficacy of combining corticosteroidsand colchicines in two patients with idiopathic sclerosingmesenteritis.

Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:684–8.

-

Bala A, Coderre SP, Johnson DR, Nayak V. Treatment of sclerosingmesenteritis with steroids and Azathioprine.

Can J Gastroenterol.2001;15:533–5.